Beams of sunlight stream through the white-framed windows of an atrium, illuminating a garden outside while casting shadows across floral wallpaper — a seemingly idyllic household. A trio of capes adorned with turkey feathers hang from the ceiling of this picturesque room, opening up the entrance to the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum’s newest exhibition “Making Home — Smithsonian Design Triennial.”

Originally part of the Cooper Union Museum, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum departed from its parent institution amid Cooper Union’s financial struggles in the 1960s, later finding a new home under the Smithsonian. It now displays “Making Home,” a collection of 25 commissioned art installations for the seventh Smithsonian Design Triennial, a series that started in 2000.

The exhibition takes up every floor of the historic museum, which was once Andrew Carnegie’s mansion. Through its installations, “Making Home” examines how design influences the physical and emotional spaces we call home.

On the first floor, designer Liam Lee and artist Tommy Mishima introduce the theme of “Going Home” with their collaborative installation, “Game Room.” Set in the spacious, oak-clad interior of Carnegie’s former office, the installation injects a sense of playfulness into the room.

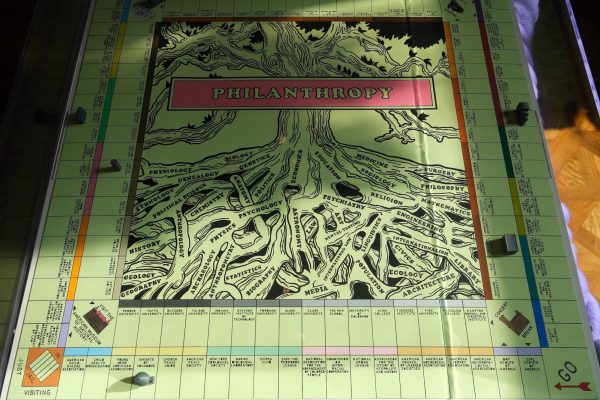

“Philanthropy,” a Monopoly-style board game, sits at the center of “Game Room.” This piece reflects the systems of education and finance that Carnegie helped cultivate through his wealth. The room also holds neon needle-felted furniture that evokes twisting vines found in a garden, which contrast the office’s dark walls and geometric flooring. Although Carnegie’s wealth can make him feel distant from the public, this room allows visitors to imagine that they are sitting and playing a game with Carnegie.

From the second floor onward, “Making Home” is less bound to the museum’s decorated interiors, instead pivoting to the theme of “Seeking Home.” Situated in a dimly lit corner at one end of the second floor, the room “So That You All Won’t Forget: Speculations on a Black Home in Rural Virginia” reflects designer Curry J. Hackett’s rural childhood in Virginia. Dried tobacco leaves — associated with slavery and health risks — are placed throughout this former dressing room, juxtaposed with objects like family paintings, skillets and a small television. This room acknowledges the complexities of home and how it can have unerasable connections to our identity and past experiences.

The last stretch of “Making Home” displays its largest installations. The third floor’s theme, “Building Home,” is clearly connected to the installations’ proposals for new communal spaces and lifestyles. Among them is Ronald Rael’s “Casa Desenterrada/Exhuming Home,” a horseshoe-shaped structure made from shelves of adobe bricks. Each brick bears engravings of names, images and artifacts commemorating the lives of enslaved indigenous laborers from Rael’s hometown of Conejos, Colorado. Simultaneously, blank bricks symbolize the undocumented lives of enslaved individuals, reflecting the fragility of home.

This piece extends around visitors like an open embrace, alluding to the idea that home is built through a sense of shared community. It emphasizes that even if our stories are erased through injustices, we live on in the home and community we connected with in our lifetime.

The myriad installations of “Making Home” invites visitors to see how design helps visualize homes of the past, present and future. The sheer breadth of artistic mediums and thought-provoking issues that this exhibition takes on also compels viewers to reflect on the complexities of home, and the word’s endless applications.

“Making Home — Smithsonian Design Triennial” is on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and is open through Aug. 10, 2025.

Contact Kaleo Zhu at [email protected].