Despite being known as one of the greatest modern portrait photographers, Annie Leibovitz is far from perfect. Recent interpretations of her work suggest her vision cannot accurately portray the natural beauty of minorities, especially black women. The Hauser & Wirth exhibition, “Annie Leibovitz: Stream of Consciousness,” invites viewers to acknowledge her missteps and appreciate her enduring impact on how we see the faces shaping history.

Leibovitz is an award-winning photographer known for her portraits of celebrities. Her work is featured in Rolling Stone, Vogue Magazine and Vanity Fair. The United States Library of Congress dubbed her a “Living Legend.” Leibovitz’s work is certainly embedded within history — she shot a Rolling Stone cover of Yoko Ono and John Lennon mere hours before his death. Her repertoire is littered with foreign officials, musicians and movie stars. Now, she’s Anna Wintour’s go-to photographer for Vogue cover shoots.

Although Leibovitz has held a fruitful career, recent photoshoots featuring figures like Rihanna, Viola Davis, Simone Biles and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson have displayed her botched shoots with poor lighting. Instead of emphasizing her subjects’ natural beauty and strength, they look ashy, worn out and faded. The lighting — which illuminates the subject in her other portraits — pulls the others into the shadows. Instead of highlighting what makes them remarkable cornerstones of modern culture, they are cast away in grim lighting. If she can’t properly light a diversity of skin tones or represent everyone’s accomplishments artistically, why should she be given so much praise?

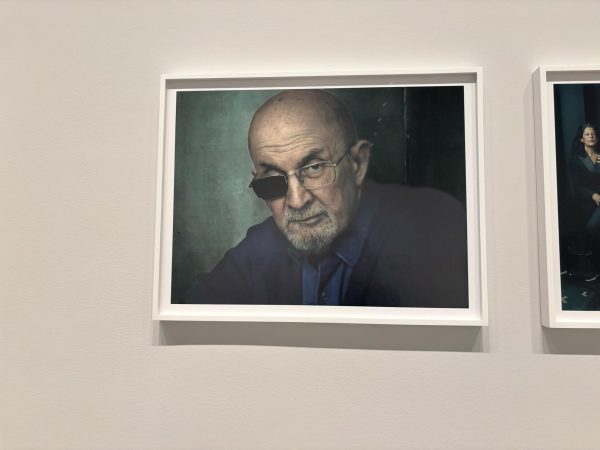

Leibovitz’s five-decade-long career often overshadows these certain instances, but these mistakes still discredit and devalue her work at capturing all types of people. In light of this backlash, clarity on Leibovitz’s artistic process seems necessary. That said, Hauser & Wirth’s gallery on the monolithic photographer allows a peek into her own thinking, touching on past iconic shoots while weaving together a retrospective of modern history through its most famous figures. By not arranging the photographs chronologically, the arrangement is a physical representation of how she associates different parts of her work. Leibovitz associates different photos with different moments, creating a new dialogue that was previously hidden. The gallery is not flashy but presents a new perspective of Leibovitz’s work.

“Exhibitions of my work are usually arranged chronologically,” Leibovitz states in the gallery’s text. “But there are some photographs… that rhyme with photographs from other places, other times. They aren’t moored to the moment they were made. I keep returning to these images.” This non-linear style combines various landscapes, objects and figures to visualize Leibovitz’s internal thought pattern of association.

The exhibition spans images of cultural touchstones — stark Icelandic landscapes, Elvis Presley’s TV at Graceland and commanding portraits of figures like Salman Rushdie and Joan Didion. Rushdie’s portrait, which was taken after a 2022 assassination attempt left him blind in his right eye, is particularly evocative. Despite this tragedy, Rushdie confidently gazes at the camera with a furrowed brow, and with a stoic expression, he declares that he will still keep working and writing, no matter the circumstances and dangers. In this case, a grim, dimly lit ambiance works in favor of the photograph, creating a stony tone with little embellishment. His glasses hide some of his expression, presenting the revered intellectual as an enigma.

One interesting aspect of the gallery is that she features some of her controversial work, including her shoot with Justice Jackson. In some instances, this bolsters the authenticity of her catalog as she upholds both her most revered images along with derided ones.

In her photograph of Justice Jackson taken at the Lincoln Memorial, she is pictured looking up and away, as if to take in the power of the monument, while the statue of Abraham Lincoln upholds the background. Except for the statue, the photograph is so darkly lit that the viewer can barely register the powerful expression on her face. Leibovitz seems to highlight Lincoln’s image rather than the woman making history. The photograph does little to showcase Justice Jackson as a powerful figure in America as a result of poor artistic choices. Whether the decision to display this photo is an acknowledgment of public opinion or a reassertion of those particular works in her catalog, they represent Leibovitz’s conscious decisions to not conceal or hide her pitfalls.

An unfinished pinboard is the most meaningful piece in the gallery. Scattered across the wall, with some crooked or askew, the images represent the complexities of modern culture. Photographs of Presidents Joe Biden, Barack Obama and Bill Clinton hang near President-elect Donald and Melania Trump posted on a gilded private jet, with Stormy Daniels’ portrait nearby, its placement lopsided. There is a grimness in seeing all of these subjects in such close proximity, but it is a remarkable display of Leibovitz’s artistic outreach and impact.

Interestingly enough, the representation of varied work in Leibovitz’s catalog reflects back onto the cultural landscape we live in today: one full of divisive and passionate narratives. Flawed and subject to bias, but somehow, an authentic representation of the world we live in today. Even with her missteps, Leibovitz’s photography mirrors society’s own complexities.

Contact Maggie Turner at [email protected].