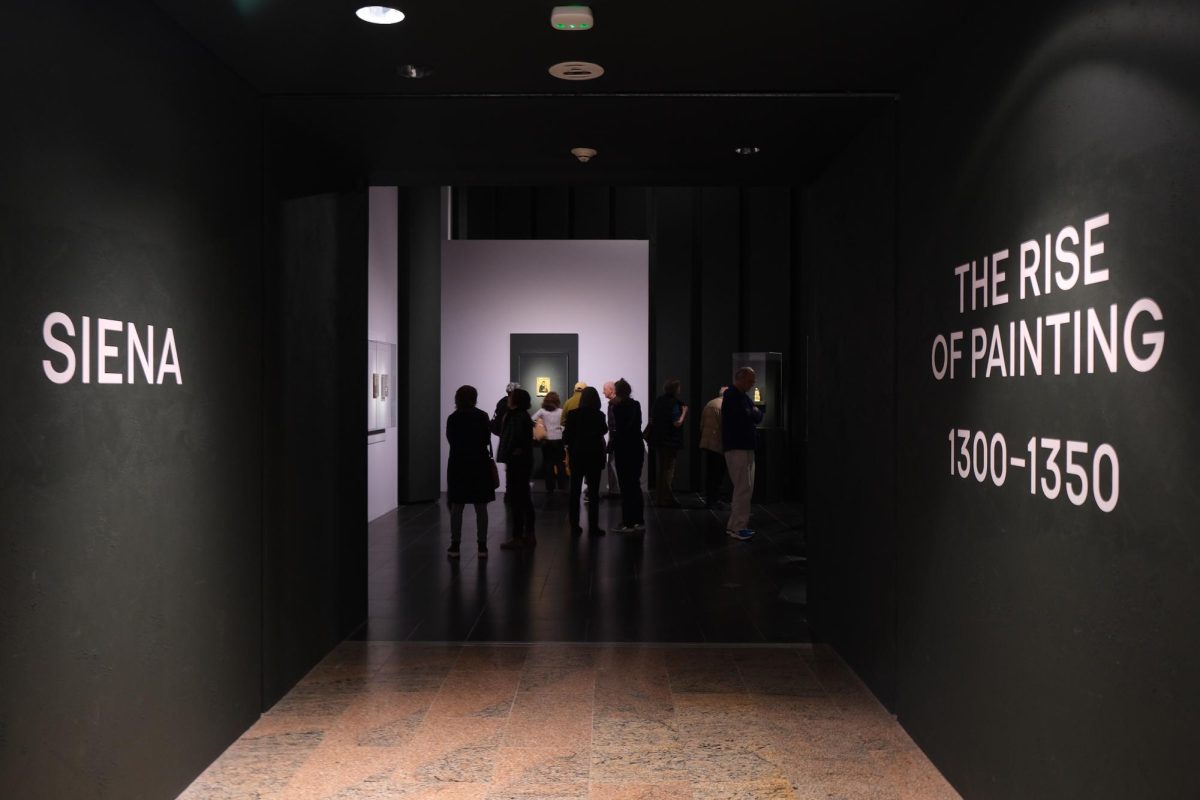

As visitors reach the end of the European painting section on the second floor of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, they come across a dark entryway with two black walls reading the word “Siena” and “1300-1350,” a time period foreign to most viewers. Once inside, visitors are magically transported to a small medieval Italian city.

“Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350” features over 100 artworks highlighting the small Italian city’s artistic significance that later influenced the Italian Renaissance. Transporting viewers to a medieval time period, artwork from Sienese painters like Pietro Lorenzetti, Duccio di Buoninsegna and Simone Martini fills the exhibition, offering a window into the often overshadowed city’s robust history.

The most exciting part of the exhibition is how it preserves each piece’s history — displaying chipped frames, cracks, missing pieces and faded colors characteristic of their age. It prioritizes authenticity over aesthetic, staying true to the city’s heritage.

Contrasting the exhibition’s large space, viewers first see Duccio’s miniature painting, “Madonna and Child.” This 11 by eight inch piece, made of shiny gold leaf on wood, shows the Virgin Mary holding Jesus, who reaches toward her face. The pair contrasts against the vibrant background, and the emotional connection between mother and child is breathtaking. The painting being the exhibit’s opener highlights the abundant talent the small city had within it.

Duccio’s famous altarpiece, the “Maestà” — which was originally created for Siena’s cathedral — sits in the exhibition’s first large section. The piece was originally almost 16 feet tall, featuring various religious scenes, such as Jesus standing center on a dirt path healing a blind man as a crowd gathers behind him, or Jesus standing atop a building casting away a demon as angels stand behind. The horizontally displayed panels fill up an entire wall of the exhibit, a hint toward how large the altarpiece was when fully assembled. Although the piece isn’t exactly in its original state, the high level of preservation allows Duccio’s details to shine even after centuries of movement.

The following section spotlights Lorenzetti’s “Pieve Altarpiece.” The altar is 9 feet by 10 feet, depicting four saints — two hold a staff while the other two carry a book — and the Virgin Mary. The leftmost panel portrays Saint Donatus of Arezzo, whose robe and headpiece are covered in ornate decorations, such as maroon and orange stars and tiny gold dragons. While the high skill level makes it hard to believe the piece was painted centuries ago, other physical qualities reveal its age. The desaturated, near-gray skin tones of the subjects are most likely a product of their time, providing an exciting glimpse into the technical limitations in the 1300s.

Tondino di Guerrino’s “Crucifix” stands in a glass case in the middle of the exhibition. The piece is beautiful with dazzling enamels that coat the cross in blues, greens and purples. A small gold sculpture representing Jesus hangs in the middle. The piece glows under direct lighting and casts a shadow in the shape of a cross on the floor behind it. The work is itself untouched, preserving the authenticity of the piece, but this strategic lighting choice adds a unique twist — drawing extra attention to the work. This addition honors the historical significance of the original artwork while elevating it with modern technology in the exhibition’s curation.

Often eclipsed by main Renaissance sites like Rome and Florence, Siena’s artistic influence rarely gets the attention it deserves. The Met exhibit is doing good to restore some of that balance.

“Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350” is on display at The Met until Jan. 26, 2025. Admission is pay-what-you-wish for NYU students with ID.

Contact Skylar Boilard at [email protected].