Content warning: This article contains mentions of violence.

Nestled in the back of the Pearl River Mart, a small art gallery awaits curious viewers. After exploring colorful aisles filled with an enticing selection of Asian snacks, trinkets and games, shoppers find themselves at the entrance of a room adorned with 23 black-and-white photographs.

“Tiny Grains: Chinatown Forever Changed, Forever Changing,” the store’s latest exhibition, focuses on photographer Edward Cheng’s documentation of Manhattan’s Chinatown during the COVID-19 shutdown. Cheng, born and raised in New York City, began photographing the neighborhood and its residents as he roamed amid the city’s standstill. The series captures daily life in Chinatown — emphasizing the community’s resilience and solidarity amid the unique challenges posed by the pandemic.

The north wall features photographs of the same cross street in Chinatown, where Cheng would station, hoping to catch a familiar face. “Joanne Kwong and Mom” is a sentimental, striking photo in its simple, yet loving, depiction of mother and daughter holding hands while walking home from their weekly shopping trip. Both fashion open-toed sandals, hold plastic grocery bags and bright smiles. In the gallery guide, Kwong describes the moment she spotted Cheng as “a warm, small town feeling, which was especially heartening during that difficult time.”

Through this informal shot of Kwong and her mother, Cheng highlights how residents maintained routine despite the significant disruptions posed by the pandemic. Given that a friendship between Cheng and Kwong emerged through the photograph, it serves to represent bonds that were forged and maintained during the pandemic, even if they were just fleeting street encounters.

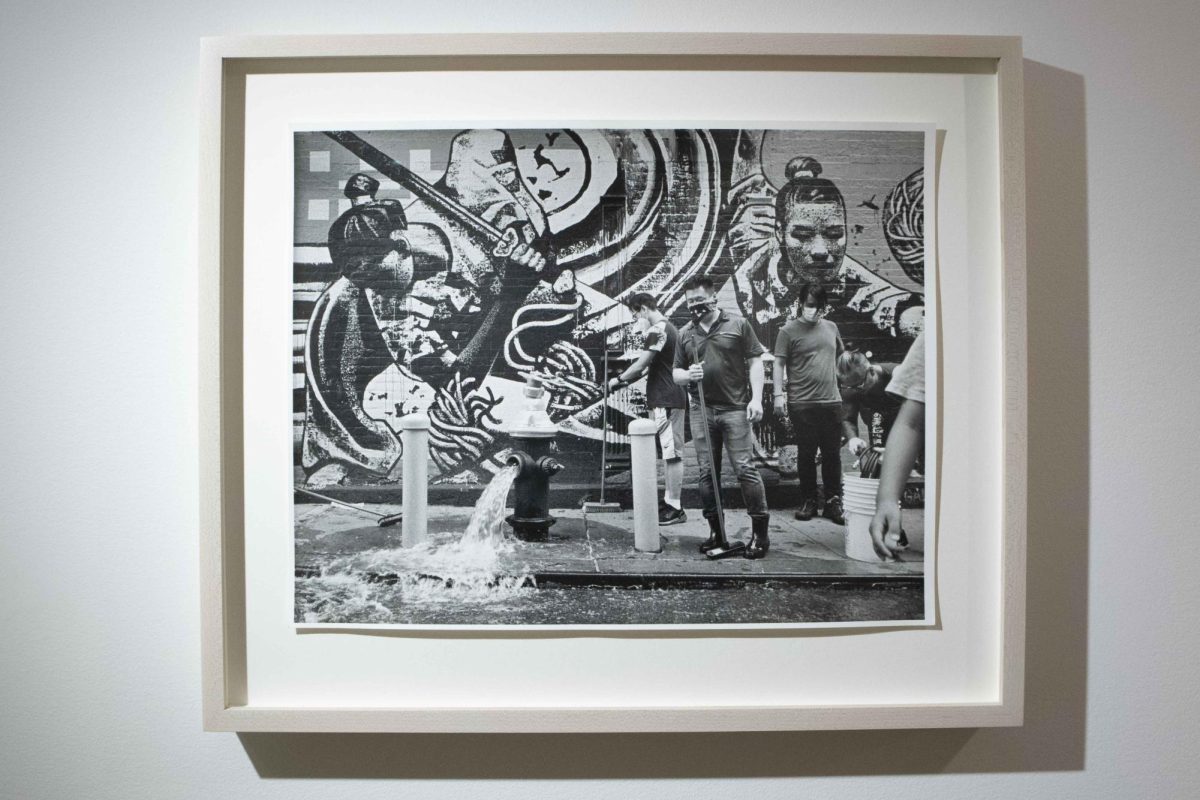

The east wall marks a shift in Cheng’s focus, showcasing four photos of people standing in front of and walking past murals in Chinatown. The last photograph, “Feminist Collages NYC, From ‘Memorial from a Femicide,’” depicts three pedestrians walking past a mural memorializing Christina Yuna Lee, a victim of anti-Asian violence. The text on the mural recounts her story, stating,“CHRISTINA YUNA LEE WAS STABBED 40 TIMES BY A MAN AND FOUND DEAD IN A POOL OF HER OWN BLOOD.” The composition of the image alongside its violent content is striking, especially within the casual context of the photograph.

The mural’s juxtaposition captures the everyday reality of Chinatown residents who navigate a neighborhood where daily life is intimately shaped by the haunting presence of anti-Asian racism. Yet, Cheng’s photograph simultaneously reflects the community’s strength to continue walking through the neighborhood as they grapple with the anger, grief and frustration.

The exhibition ends on the final wall with “Jia Sung. ‘Photographic Justice,’” a shot of a trail of lanterns floating in the wind against a backdrop of scaffolding. The photograph’s lack of context and inherent mundanity moves audiences to gain a deeper understanding of the lanterns themselves — a grassroots effort by Light Up Chinatown to increase the safety and maintain the aesthetic appeal. The lanterns symbolize a communal presence, one that watches over and envelopes residents throughout their daily lives. Although Cheng doesn’t showcase the people who inhabit it, they are known to viewers in this wind-swept view of their artistic efforts to ensure Chinatown’s longevity. Once again, Cheng displays residents’ struggle to maintain their community through the physical construction and decoration of the community itself.

“Tiny Grains” is an exhibition that audiences might overlook because of its simplicity and small size. Nonetheless, Cheng’s photography transforms the gallery into a deeply emotional space, where care and community is celebrated. In the midst of society’s incessant struggle back to normalcy, Cheng encourages viewers to pull back a little and commemorate one another’s resilience, using the local yet ever-universal streets of Manhattan’s Chinatown as his medium.

“Tiny Grains” is on view until Jan. 12, 2025 and is open to the public during business hours.

Contact Julia Kim at [email protected].