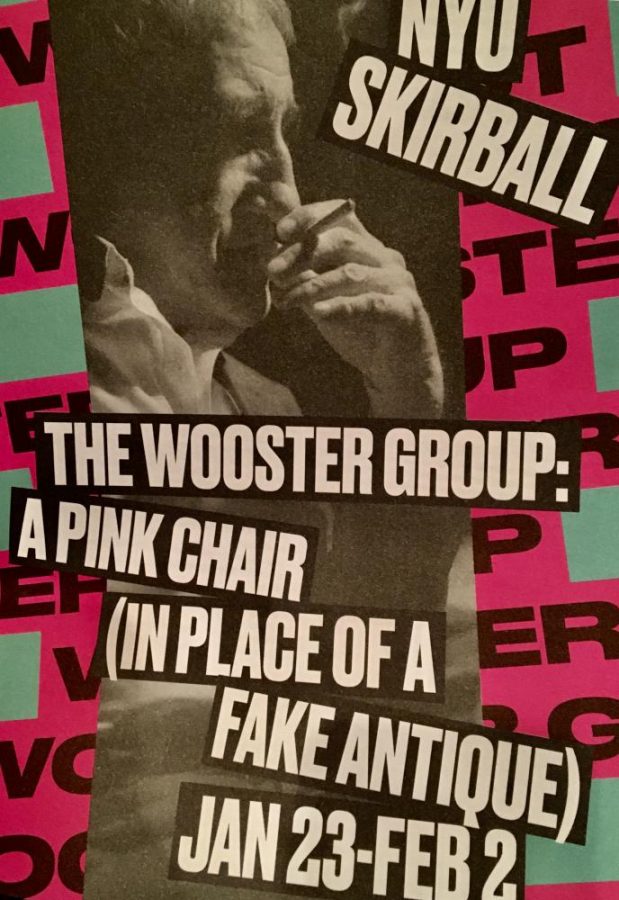

The Skirball Center transformed into a theatrical time capsule for The Wooster Group’s “A Pink Chair (In Place of a Fake Antique).” Running from Jan. 23 to Feb. 2, the performance recollected Tadeusz Kantor, a 20th century Polish director, and his play “I Shall Never Return.” While there was almost no plot, The Wooster Group succeeded in illustrating what it means for an artist to be forgotten and eventually reborn through remembrance.

Upon entering the auditorium, the gothic stage had an industrial feel with metal tables, contrasting lights and shadows that produced a gray effect, a candelabrum and a sewing mannequin scattered the stage. When the lights dimmed, a TV played an introductory video in which Kantor, played by actor Zbigniew “Z” Bzymek, read his manifesto. A voice-over simultaneously played a recording of the manifesto to create an echoing effect. Immediately after, another video, “I Shall Never Return,” introduced the film motif of viewing. For the rest of the show, clips from Kantor’s work were reenacted alongside the actual rehearsal footage. Typically, this synchronization is difficult to achieve, but with Elizabeth LeCompte’s direction, the entire company made the combinations seem effortless. This artistic decision was inventive, but unfortunately did nothing more than memorialize Kantor. There was no story aside from the message of remembering the dead, making this more of a tribute than a legitimate theatrical production.

One dynamic aspect of this show was its ability to overwhelm the audience with sound and the multi-purpose set. The production featured live singing and a violin combined with musical recordings in an attempt to evoke sadness. While the music set a somber tone, all of the different sounds felt extremely overwhelming. Not knowing who or what to listen to, the dialogue was difficult to hear which inhibited comprehension. Nevertheless, nothing enchanted the audience more than the show’s final sequence. As the TV and platforms magically transformed into a ship, the theater filled with sounds of crashing waves and the ensemble’s disturbing, hushed singing. When the final note rang out, the entire stage went black, leaving the audience in a haunting, but resonant silence. This dramatic moment was a poignant part of the production because it forced audiences to think about what they had just witnessed.

Bzymek’s performance was unsettling, but remained engaging for the 70-minute show. His acting felt distant from the other actors, just how Kantor would have remained physically removed from his performers as a director. Everything — from his posture to lifeless countenance — demonstrated that he was deceased yet able to watch his imagined world come to life again. The rest of the company only complimented the disquieted ambiance with their evocative singing, movement and dialogue.

Discussing the idea of “duch,” or forgotten spirits, the show argued that other art forms like painting or film are remembered forever, but theater productions simply disappear after the final curtain, left only to be archived by people’s memories. Even though Kantor passed, fragments of rehearsal footage, writings and individuals’ memory allowed his legacy to live on and were revived by this production. Kantor’s director chair symbolized the great theater he created in it and his imprint on society; although he was not alive to sit in the seat for this performance, his spirit lives on through audiences — a sentiment that is undeniably beautiful.

While “A Pink Chair (In Place of a Fake Antique)” is not traditional by any means, a greater presence of conflict would have grounded the show more. However, the overall message about revitalizing forgotten works or people was applicable to our rapidly changing world and reminded the audience to value past artists and their contributions; they may not actively cross our minds, but they undoubtedly contributed to modern theater today.

A version of this article appears in the Monday, Feb. 3, 2020, print edition. Email Sasha Cohen at [email protected].