Having a roommate isn’t foreign to most New Yorkers or college students, although having one in your 50s and 60s in Iowa is a bit more unordinary. Nonetheless, Jen Silverman’s play “The Roommate,” now playing at the Booth Theatre on Broadway, embraces this unusual reality.

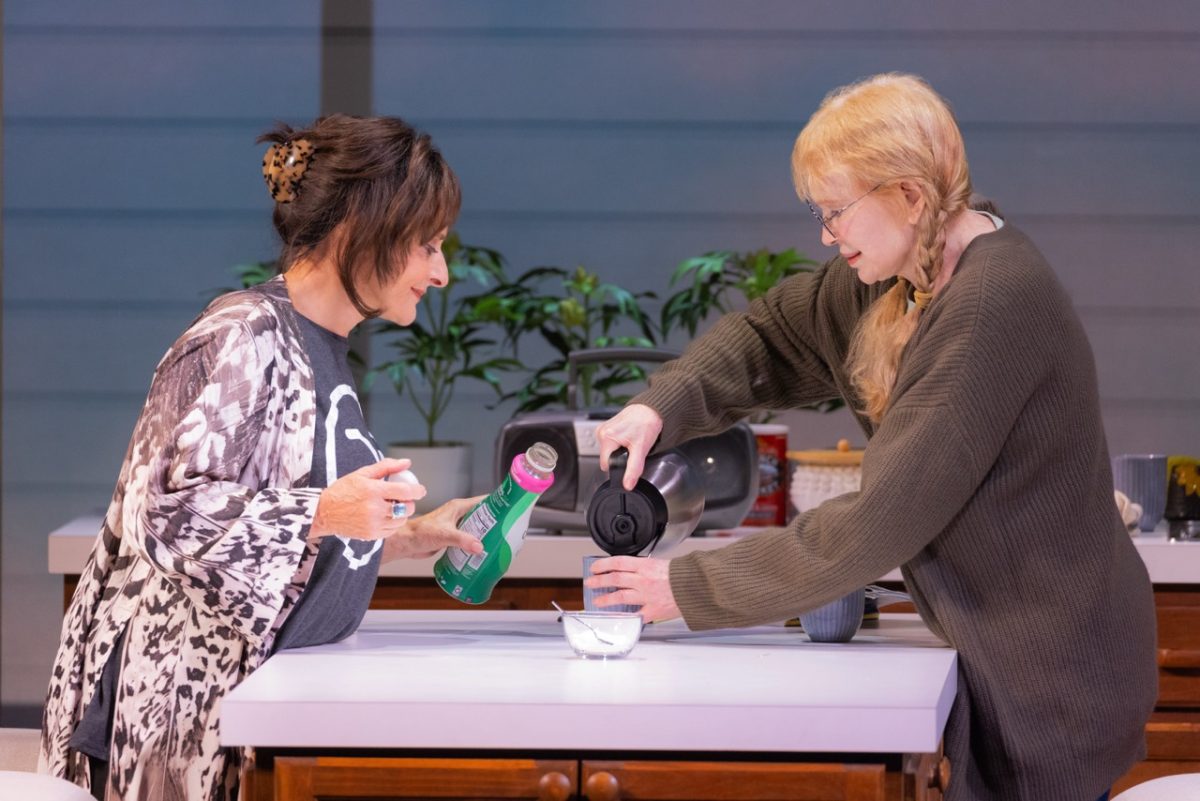

Once the stage lights come up, the audience is greeted by a slice-of-life comedy. The differences between the two characters are immediately apparent as Robyn (Patti Lupone) moves into Sharon’s (Mia Farrow) Iowa City house. Robyn is a pessimistic New Yorker in her 50s, and Sharon is a glass-half-full 65-year-old from Indiana. They become quick friends despite their differences as they bond over their complicated relationships with their children, a love for causing mischief and a shared entrepreneurial spirit. Sharon’s childlike curiosity about her new roommate leads her to constantly implore Robyn for details about her past. Robyn is unrelenting, but as more and more questions pile up, they both have to reckon with the previous mistakes in their lives that have led them to where they are now.

With her midwestern perspective, Sharon’s concern over Robyn’s experience living in the Bronx is as endearing as it is funny. Farrow’s performance makes every word come across as overwhelmingly sincere, even when questioning Robyn about whether a vegan diet includes meat or eggs. Farrow finds the humor and joy in everything her character does, causing the audience to cling to her every word. LuPone, a three-time Tony Award winner and Broadway legend, plays Robyn’s stone-cold demeanor with a loving hand. When Robyn pushes back against Sharon’s belief that most New Yorkers are gay with the line, “I think actually there are a lot of straight people in New York,” LuPone is careful to ensure that her sarcasm never crosses the line into cruelty.

What starts as an economic exchange between Robyn and Sharon quickly turns emotional as their lives become increasingly entangled. However, the play struggles to present their emotional struggles authentically. The material is frustratingly hollow, brimming with the potential for deeper interpretations but never fully committing to it. The writing touches on morality, loneliness and identity, but only half-heartedly alludes to the topics through comedy. This hesitation to explicitly examine these ideas makes the play feel surface level, lacking any distinctive point of view.

Silverman’s material isn’t as inspiring as the performances. Approximately 80 minutes of the 90-minute play are jokes, mostly repeated one-liners that quickly lose their novelty. Much of the storytelling depends on an invisible character on the other side of a landline, with one actor stuck on stage with the phone and drowning in the silence of the unheard person on the other end. It’s hard to achieve any sort of dramatic payoff when half of your play relies on the actors and audience hearing nobody. The emotional moments scattered throughout the play come so far out of left field that the audience isn’t sure whether they should be laughing or crying, and the writing isn’t strong enough to encourage either of the two. Robyn’s strained relationship with her daughter is revealed through a phone call, but the scene then shifts to Sharon joking about her son’s girlfriend. The audience never fully understands the character of Robyn’s daughter after that because the rest of the play only makes vague references to her.

The production of the play does very little to support its jokes. The set by Bob Crowley is empty where it ought to be full and cluttered where it ought to be simple. An attempt at a realistic set design of a kitchen drowns out the actors, and the wooden beams used to suggest the roof of the house draw the eye to dead space on stage. The lighting design by Natasha Katz is pretty, but fails to evoke anything in the audience beyond its appearance. More often than not, the stage is plainly lit with a projection of a blue sky and clouds behind the set. One lighting sequence calls back to Robyn’s fear of tornadoes and another shows the sun rising on an empty stage, but neither of these moments lasts long enough to suggest any deeper meaning.

Director Jack O’Brien highlights the play’s emptiness before it even begins when the two actresses walk onstage with their names projected onto the set above them. LuPone and Farrows’ names are already on the marquee outside the theater and inside the playbill, so this gesture makes the experience about the stars rather than the play itself. O’Brien may use it to get the inevitable first-appearance applause out of the way, but what it really does is set up the beginning of the production’s failures: It isn’t an honest depiction of life but a performance of one.

If you want to see a Broadway legend like LuPone up close or see Farrow show off her comedic chops, “The Roommate” isn’t a bad time. However, if you want to watch a thought-provoking play that leaves you ruminating on your life, you’re better off staying in with your actual roommates.

Contact Chantal Mann at [email protected].