Ascending the steps of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a vibrant banner adorns its exterior and advertises its newest exhibition, “Mexican Prints at the Vanguard.” The entrance to the gallery mimics this energy with a mustard yellow wall marked with the exhibition’s title, warmly welcoming visitors into the space.

“Mexican Prints at the Vanguard” showcases over 130 works of printmaking by many artists from the 18th to mid-20th century. Mexican printmaking is a rich part of the country’s history, having served to educate and influence the Mexican people. These prints appeared in newspapers, books and advertisements, using the medium as a primary mode of communication to broadcast the contrasting concerns of the government and the citizens. The exhibition’s prints convey the collective memories of the Mexican people and their culture against a shifting political backdrop.

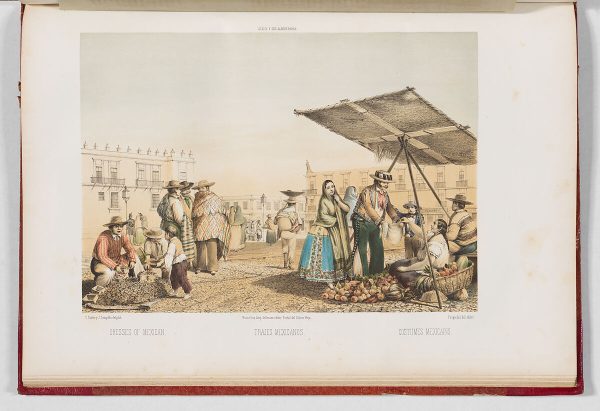

“Mexico y sus Alrededores. Colección de monumentos, trajes y paisajes,” created by various artists, is one of the earliest works selected in the exhibition. Printed in 1855-56, the piece depicts a market in Mexico City near the National Palace, where vendors sell their goods. The buildings in the background are beige and subdued, highlighting the more colorful subjects in the foreground. A young woman on the right of the piece wears a china poblana, a traditional style of dress for women in Mexico, and pulls her shawl tighter across her body. The men wear sombreros, wide brimmed hats that protect them from the sun, and sell their goods in the market. This piece highlights traditional dress and allows viewers to glimpse into the daily life of the average person in 19th-century Mexico.

Prominently showcased in this exhibition, José Guadalupe Posada was a key player in “establishing the global identity of Mexican art,” creating more than 15,000 prints during his career according to the text on the walls of the exhibition. He illustrates “broadsheets, reports of crimes and natural disasters, and ballads (corridos) about popular heroes, bandits and current events.”

One print showcases Posada’s classic technique of depicting individuals as skeletons for social critique. In this illustration, skeletons in various costumes –– such as wings, top hats and cloaks –– race on bikes alongside each other. The race seems to have taken an aggressive turn. Having been crushed by their competition, a few skeletons lay on the road in agony. Each of these skeletons represent a newspaper, satirically commenting on their impetuous competition created by the tense political environment.

The Mexican Revolution, a prominent feature in the exhibition, was catalyst of the development of contemporary Mexico. The revolution began on Nov. 20, 1910, with the rebellion against authoritarian President Porfirio Díaz, and what followed was 10 years of armed regional conflict. A presiding demand of the people during the revolution was the redistribution of the agrarian land to peasants, which had been taken during Diaz’s rule.

“Plate 1: Indigenous Mexicans being forced from their land, from the portfolio ‘Estampas de la revolución Mexicana,’” created in 1947 by Francisco Mora, is the first piece in a collection of 85 prints depicting events surrounding the war. On the right side of the piece, a man wearing a sombrero sits on a horse and raises a whip over his head. In front of him is a line of Indigenous people being forced to leave their farmland. The line of people continues into the hills in the background. The Indigenous person in the front of the line holds their belongings in their proper left hand, their child in their proper right, and keeps moving forward.

The war ended with the creation of the Constitution of Mexico in 1917, and the country entered a period of reconstruction. This period included, according to the exhibition description, “free-market capitalism, the redistribution of land back to farmers and a cultural sea change that promoted secularism and core values associated with nationhood.”

Printed in 1924, “Rich people in hell” by Jean Charlot embodies a common sentiment held by political artists at the time: hatred toward the rich. This sense of hatred grew during the revolution and gained more political strength once the farmers were given back their land. The work is a woodcut piece with a wealthy man and woman carved into the center, and their affluence is indicated by the man’s top hat and the women’s pearls. The people pose with shocked expressions and appear to be falling as frightening figures surround them. Some of the figures have devil horns and others hold pitchforks, while the negative space is used to create flame-like structures. Prints like this provided citizens with a vehicle to express their discontent towards those in political power.

“Mexican Prints at the Vanguard” spotlights art’s boundless potential to spark change in the face of political distress, documenting this change for future generations to reflect on. Principally, the exhibition highlights the artists as vanguards, those who pioneer the development of new ideas, leaving a colorful archive of Mexico’s history. Viewers travel through time and gain insight into the struggles, triumphs and resilience of the Mexican people during a period of political and social turmoil. This exhibition provides both an education in Mexico’s history and a moment to reflect on how art has and continues to document our lives.

“Mexican Prints at the Vanguard” is on display at The Met through Jan. 5, 2025. Admission is pay-what-you-wish for NYU students with ID.

Contact Siobhán Minerva at [email protected]