If you care about movies, you’ve probably seen recent backlash against the use of generative artificial intelligence in best picture front-runners “The Brutalist” and “Emilia Pérez.” If you’re alarmed, that’s completely natural. Despite its declining ratings over the past few years, the Academy Awards still have considerable cultural capital and, at first glance, it seems particularly offensive that the two films with the most nominations this year cut corners.

In an interview with Redshark News, “The Brutalist” editor Dávid Jancsó said that generative AI was used in two ways: dialogue adjustments and architectural designs. Ukrainian software company Respeecher trained an AI on the lead actors’ voices to adjust some of their vowel sounds to make the Hungarian dialogue more accurate. This was done with the actors’ consent, and the AI effectively molded the actors’ voices to mirror Jancsó’s pronunciation as a fluent speaker.

Upon further examination, this issue has further nuance. Director Brady Corbet clarified in a statement for Deadline that the film’s production designer Judy Becker and her team “did not use AI to create or render any of the buildings,” and that “all images were hand-drawn by artists.” However, this seems to be contradicted in a 2022 interview where Becker said she used the AI program Midjourney “to create three Brutalist buildings” and had them “redrawn by an illustrator.” The sequence at the end of the film shows these modified drawings.

“Emilia Pérez” director Jacques Audiard claimed that for some of the songs, the team used Respeecher — the same software company as “The Brutalist” — to extend the vocal range of lead actress Karla Sofía Gascón. Respeecher trained AI to effectively auto-tune Gascón’s vocals using the voice of co-composer and French popstar Camille. Gascón is also under fire for her recently resurfaced racist tweets, in addition to AI usage in her performance.

Despite concerns surrounding the implication of using AI, the training data for these vocal models was ethically sourced, and its use did not rob creatives of work, compensation or otherwise replace creativity. The models were trained on voice samples provided for by the actors and adjusted with the voices of others already on the team. The process is similar to popular AI videos on social media involving character or celebrity voices, except in this case, both parties actually consented.

If light touching up is enough to disqualify a film from awards eligibility, take away Rami Malek’s Oscar for “Bohemian Rhapsody,” where vocal stems from Freddie Mercury were spliced with Malek’s vocals. Aiding actors to better embody their characters with technology does not rob them of the talent they put on screen, but obfuscates more important concerns with using generative AI for art.

But why did Becker, an Oscar-nominated and talented production designer who has worked on highly artistic films like “Brokeback Mountain” and “We Need to Talk About Kevin” decide that her team should use Midjourney to pre-render architectural sketches in “The Brutalist,” even if for just three images? Are she and her team lazy? Does she not value artistic craft? Or was she working on a gargantuan, star-studded three-and-a-half-hour-long film with a paltry $10 million budget and razor-thin margins? As a matter of principle, I do not support Becker’s use of Midjourney, but I am much more frustrated that this movie was given a budget $90 million less than 2024 best picture winner “Oppenheimer,” a drama of similar scope and length.

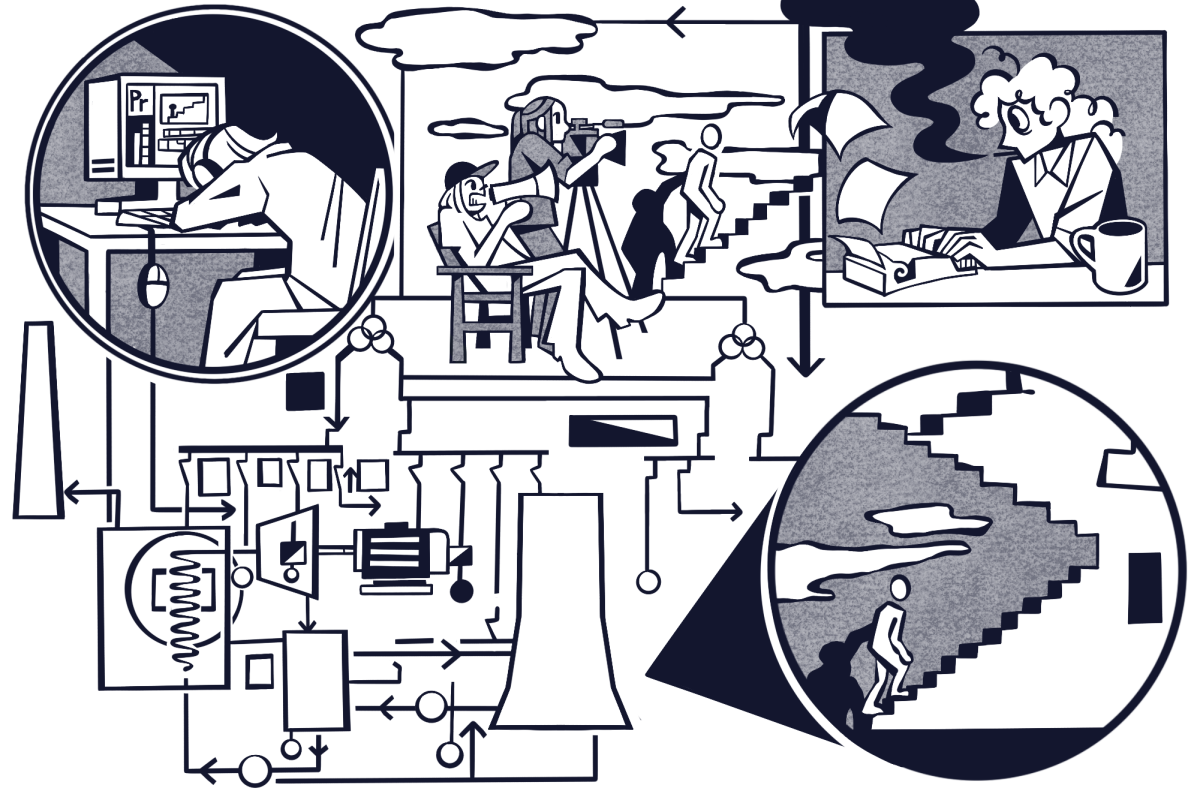

The acting nominations for “The Brutalist” and “Emilia Pérez” don’t represent much of a marked change from the current paradigm in audio engineering. However, I can’t help but worry just a little about the precedent that “The Brutalist” sets with its use of Midjourney. The Academy Award nomination is less concerning — the touch-ups real artists did in post production show that artists are being awarded, not thieving bots — but the cost-cutting miracle that the film represents seems like a slippery slope. Whether or not “The Brutalist” is terribly profitable, it is a $10 million film which could’ve easily cost much more had the accounting not been completed with a fine-toothed comb and some of the work been streamlined by AI. What happens when the wealthiest CEOs — who as of 2022 now make an average of 344 times the average salary of a typical worker — decide to gut the production budgets of more films? Do we want to live in a world where computers, rather than enhancing our creativity by streamlining work, reduce art to a mere tool for generating capital?

Contact Max Vetter at [email protected].