After groggily dragging my exhausted and hungover body out of bed, I crept outside my dorm for a breath of fresh air and headed to the cinema. I squinted at my phone to check for available showtimes and saw that “The Boy and The Heron” was screening at the Angelika Film Center. Suddenly, while looking at the poster for the film, my shoes felt a little bit bigger and it felt like I was a kid again.

If you asked anyone who grew up in an Asian household what Studio Ghibli movies mean to them, you’re likely to hear a passionate answer on how the animation studio’s films played a big part in their childhood — it’s our version of Disney. These are films that we’ve watched since we were young and that occupy a special place in our hearts, even if we haven’t seen them for ages. From Kiki flying on her broom through the night sky with her black cat Jiji in “Kiki’s Delivery Service” to Sen and No-Face riding a train headed to the twilight horizon in “Spirited Away,” Ghibli’s images are engraved into our core memories.

As a person born and raised in South Korea, Ghibli films also stand out as works of animation that represent East Asian characters and narratives. While most animated kids films took place in a faraway land of an imagined America or Europe, Ghibli films represented values that were embedded in my upbringing. I still remember the shock I felt when I realized that Ghibli films were originally from Japan since the films felt so natural and relatable in their Korean-dubbed versions.

But at their core, Ghibli films mean so much more than just childhood nostalgia or empowering representation to their fans. They are an indication that there is a bigger and much harsher adult world outside the bubble of childhood. Ghibli films, for all their surreal spectacle, have a dark and gritty quality no other mainstream children’s animations have.

The images are much more violent and realistic. The threats are literal and nerve-wracking. The stories feel more arcane and epic. “Castle in the Sky” has one of the most terrifying depictions of weapons of mass destruction, while “Princess Mononoke” shows the astonishing power of natural wonders. Some scenes even feel like they belong in horror films. I still remember being afraid of fur coats after seeing the Witch of the Waste in “Howl’s Moving Castle.”

From all these artistic choices, we could feel that there was something deeper hidden behind the swashbuckling adventures, even as children. They were our first encounters with mature ideas like war, environmentalism and grief. Ghibli films widened our perspective of the world, serving as a bridge between childhood and adolescence.

While Ghibli films opened the doors to the grown-up world when we were kids, they remind us of our innocence and childhood as adults. For some reason, the nostalgia I feel from Ghibli films feels more sentimental than most of the media that we loved as kids. As adults watching these films, our eyes begin to drift to the ceaseless vibrance of childhood and the magical worlds of endless imagination captured on the screen.

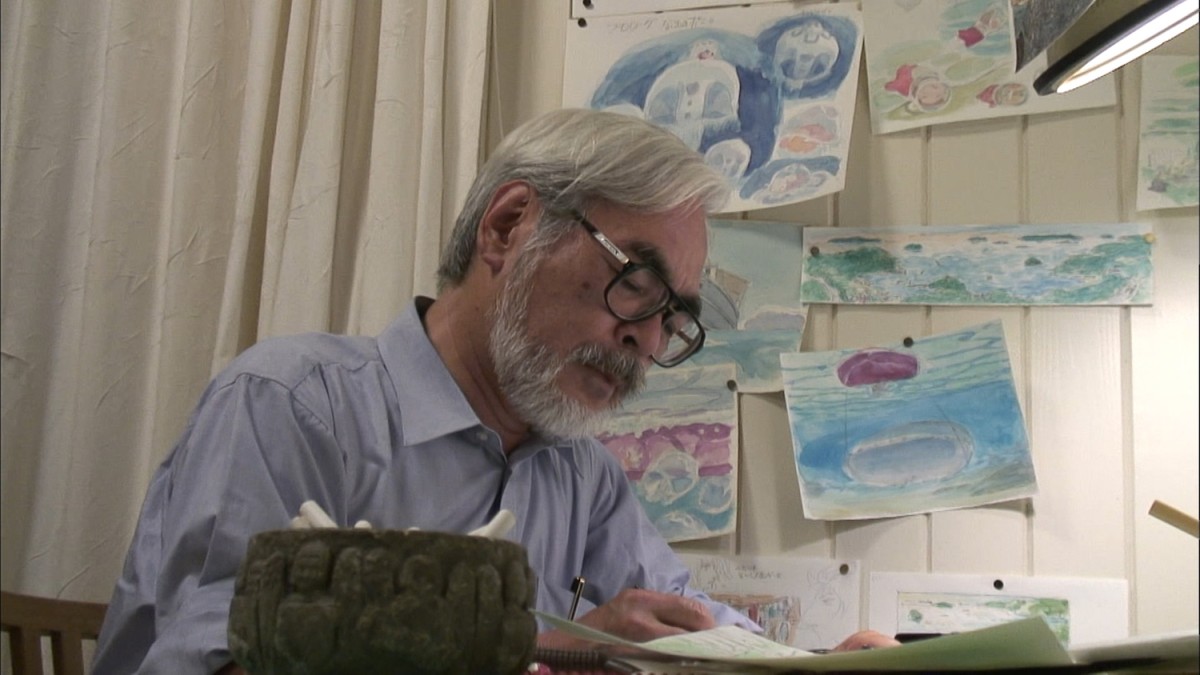

They remind us of the things we might have lost along the way — whether it be our innocence, old friends, imagination or past memories. Ghibli films not only make us yearn for our idealized childhoods when things were much more magical, but also make us reflect on ourselves and what we once had. Interestingly, this is also what Hayao Miyazaki did with “The Boy and The Heron.”

In “The Boy and The Heron,” Miyazaki turned an autobiographical memoir into a vibrant adventure into the mystical world. Through carefully-woven homages to and motifs from his past works, he reflects on his life by explaining to the audience what led him to follow the path of an artist. Though Miyazaki has again and again come back from retirement, it is very fitting that what he calls his final film puts himself back at the peak of his innocence, just like his films do for us. The film’s original Japanese title is “君たちはどう生きるか、” which directly translates to “How Do You Live?” By showing the pathway he walked in his life, Miyazaki asks the question “How Do You Live?” to the audience his films have fathered into adulthood.

Contact Tony Jaeyeong Jeong at [email protected].