As the unyielding forces of social media platforms like TikTok and Letterboxd continue to condense the world of cinema into addictive one-line reviews and jarring music video edits, the most popular opinions of online film enthusiasts are amplified, seemingly becoming universal. With the total democratization of film criticism, audiences hold films — and, by extension, filmmakers — to a high standard, with each of their works being meticulously analyzed and broken down by a harsh online community.

A select group of artists, performers and cinematic luminaries finds itself at the center of this discourse. They are not simply human. They have transcended to the status of messianic figures — saviors of an art form that is constantly on the verge of death and epochal change. Like a congregation of rabid zealots, legions of armchair critics and film bros get on their knees to praise films, lambasting anyone who contradicts their holy judgment.

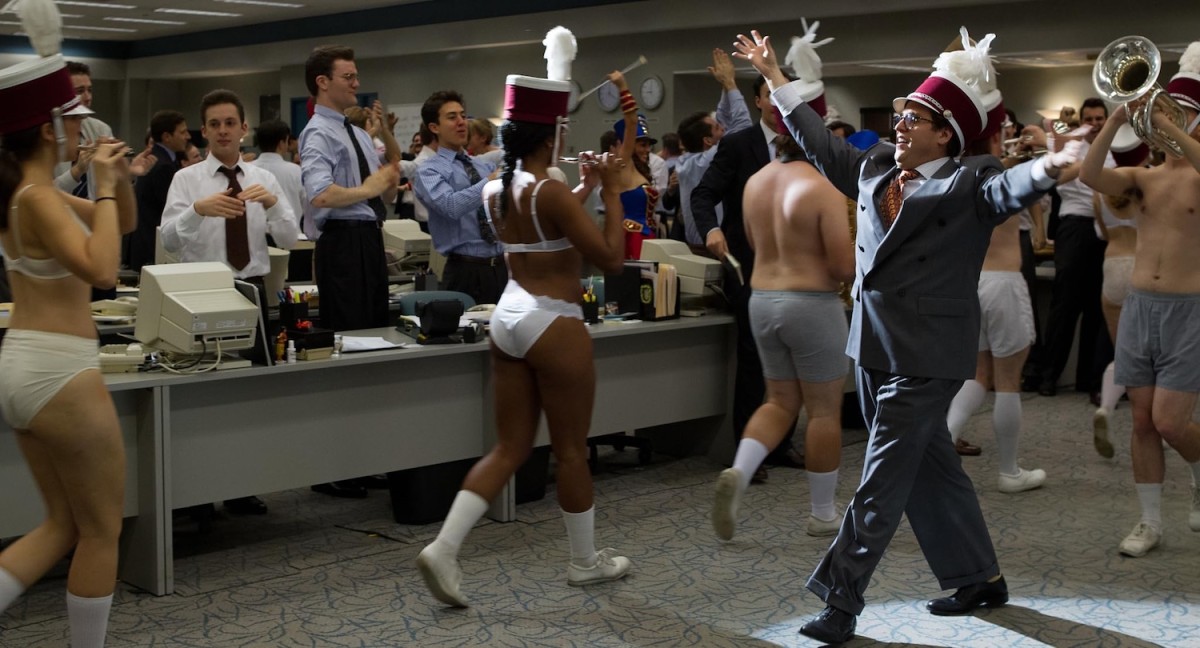

This obsessive nature of fandoms is most apparent in the discourse surrounding Martin Scorsese’s Jordan Belfort biopic, “The Wolf of Wall Street” (2013). A decadent cocaine-fueled foray into the infamous Stratton Oakmont offices, the film is based on Belfort’s memoir, which shares the movie’s name. The three-hour tour of corporate America’s opulent underbelly has been lauded by critics and fans who consider it a modern masterpiece. Despite the continued praise for the film, though, it is undeniable that the film’s presentation of Belfort and its reception have developed into a toxic element of contemporary culture. With the release of Scorsese’s newest film, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” it seems pertinent to re-evaluate the impact of one of the most pivotal works of his career and the toxicity “The Wolf of Wall Street” seems to incite.

The New Yorker’s Richard Brody defends the film’s exuberant glorification of toxic finance office culture as a representation of the day’s political moment. He argues that critics who find themselves repulsed by the film are engaging in an exercise of moral superiority, protesting all too much their immunity to the film’s temptations. The film holds an average four-star rating, and Letterboxd reviews from users like Ticker2000 assert that watching the film is akin to seeing “a Dali or Pollack [sic] in person,” and that “living to see this achievement in film-making only makes someone’s life more full.” The consensus appears to be that the film is nothing short of a miracle — that it’s Scorsese’s crowning achievement in his filmography of crooked and flawed men.

Jordan Belfort slots perfectly into Scorsese’s canon of contemptible men. He may not be a hitman for the Italian mob like Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill or a wife-beating boxer like Robert De Niro’s Jake LaMotta, but Leonardo DiCaprio’s Belfort is a predator consumed by masculine pride. All in an effort to stay afloat in the all-consuming torrents of a late-stage capitalist society, he pops Quaaludes and smokes crack, further spiraling right into the palms of his greatest nemesis — the federal government. Unlike Scorsese’s other frontmen, however, Belfort is completely devoid of any humanity at all. He is purely stimulated by financial gain.

Belfort profits off the everyman, cheats on his wives, rats out his accomplices and never truly faces the consequences of his actions. How do we find a way into such an innately loathsome character? While cinema often presents amoral or unlikable protagonists, these characters typically have some form of humanity or nuance that the audience can appreciate. Scorsese and DiCaprio, however, leave nothing for viewers to latch onto. Underneath a seething infatuation for money and luxury, Belfort’s character is completely hollow. He is a symbolic representation of the mechanisms that fuel corporate America.

While moviegoers shouldn’t expect fictional protagonists to embody a morally just and politically righteous path, the filmmaker must humanize its subject. In a medium that relies on channeling empathy, what happens when a film fails to build an emotional connection between its viewer and the main character? You begin to ask why you care, and what ensues is a complete dissociation from the narrative playing out on screen. No matter how epic the yacht party is or how thrilling the financial stakes are, there is no reason to root for — or even care about — Belfort. He is not a redeemable villain, nor even a morally nuanced anti-hero. He is simply an objectively repulsive manifestation of society’s worst impulses.

From even just the first five minutes of the film, I prayed for the inevitable downfall of the Wall Street titan. This is not because I feel as though I have a moral authority over the film’s depiction of Belfort’s crimes, but rather because of Scorsese’s failure to place victims at the forefront. There is a fine line between navigating the morally gray and glorifying human suffering. Accepting the claim that everyone is vulnerable to the temptations that consumed Belfort effectively implies that all humans are vapid creatures who lack consciences.

A conversation about a film like “The Wolf of Wall Street” would be incomplete without considering the wider culture around the film’s reception. While a filmmaker’s intent may be one thing, art does not exist in a vacuum of highbrow critical analysis. A project’s evolution as a cultural entity is also important. Scorsese’s fans may argue that the film successfully illustrates the rise and fall of a flawed character, but Belfort isn’t just a character — he’s a real person.

With 2.1 million followers on Instagram, the real Jordan Belfort continues to enamor and hoodwink individuals at a large scale. Under a post promoting Belfort’s latest book tour, the comments section is filled with users praising Belfort as a “mentor,” an “industry expert” and the “goat.” TikTok and Instagram edits use quotes from the film like revolutionary chants to rile up the masses of overworked business school students. Despite being ordered to pay at least $97 million to his victims, Belfort has yet to pay back the majority of this sum, and he continues to make a living from giving speeches and profiting of his personality.

Perhaps “The Wolf of Wall Street” truly is a representation of our times. Instead of the crooked protagonist seeing a tragic downfall at the hands of a benevolent government, corporate injustice continues to thrive. Maybe what resonates with viewers is not the temptation of a lavish lifestyle, but rather the dream of being able to live a life free of consequence, as an agent who operates outside the matrix of legal order and political society.

With sigma bros and gym lads screaming their subversive doctrine at the top of their lungs, decrying the emasculation of the modern man, it’s easy to think that the toxicity of “The Wolf of Wall Street” is representative of modern cinema and culture as a whole. In reality, the average person is able to approach the world with more nuance and compassion, not purely through a cynical lens.

Contact Mick Gaw at [email protected].