Q&A with ‘Rock Bottom Riser’ director Fern Silva

WSN spoke with Fern Silva about Hawaii, Dwayne Johnson, colonialism and cinema as a point of inquiry.

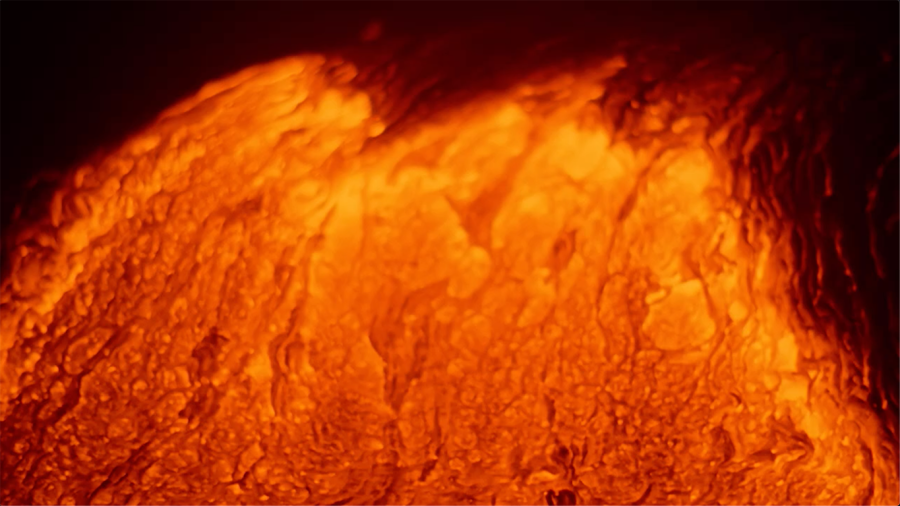

Fern Silva’s “Rock Bottom Riser” explores astronomy, navigation and colonialism as told through cultural identity and the Hawaiian landscape. The director strives to reinvent cinema as a means of visual activism. (Image Courtesy of Cinema Guild)

March 7, 2022

At first glance, Fern Silva’s “Rock Bottom Riser” is a documentary about Hawaii. But through Silva’s tapestry of visceral sights and sounds, it becomes a sui generis piece of filmmaking, exploring a history of astronomy, navigation and colonialism.

[Read more: Review: ‘Rock Bottom Riser’ rocks]

“Rock Bottom Riser” embodies a freshness in filmmaking that rejects the norms of Hollywood. Instead, it develops a new style that demands audiences become active viewers — not just passively consuming narratives, but using films as jumping-off points to embark on a voyage of research and activism relating to the subjects depicted.

WSN spoke to Fern Silva about his unique form of filmmaking, Hawaii, cultural identity, landscape and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. These topics speak to the director’s deep interest in using cinema as a means for getting viewers to take active stances toward problems in society.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WSN: Why did you decide to make a film about Hawaii and resistance?

Fern Silva: I really started thinking about making this film in 2009, when there had been an agreement that Mauna Kea was going to be the construction site for the new Thirty Meter Telescope. I read that somewhere — I can’t remember where now — but that really took me down this path where I just started pulling research from all these places, and because I felt so engaged, I had to begin digging into Hawaiian history.

The other thing too is that I made this relationship between the building of this telescope and astronomy based on my knowledge of Polynesian voyaging, ‘cause when I was younger I was obsessed with navigation and exploration. I was obsessed with Polynesian voyaging because I thought they were the greatest navigators to ever live, partly because they were able to explore the Pacific around six to seven thousand years ago and arrived in Hawaii around 2,000 years ago without any instruments.

So, I was thinking about that around 2009 and I wasn’t sure I was going to make a film, but the years rolled by and I had friends on the Big Island who I’d have offhand conversations with, so these ideas started to develop more and more, and I had a close collaborator who was spending a lot of time there and encouraging me to make a film and then things started to unfold. You know, there’s the protests of course, and Mauna Kea has now really become this symbol of resistance against corporate interest.

WSN: Your film reminded me of Patricio Guzmán’s “Nostalgia for the Light” in that it digs into the landscape it’s looking at to unearth larger truths relating to colonialism. What do you understand through landscape and how do you go about recording it? How do people define Hawaii and how does the terrain define them?

FS: I like to think of landscape as the embodied history of popular culture, the way it’s been commodified, the way it’s been affected by colonialism or some sort of occupation, and the way it looked and existed before any occupation as it relates to mythologies about a given place. I think that’s all sort of intertwined in landscape. I always think of cinema as this vessel for mythologizing a place because it often looks at places as other places. Hawaii, for example, hosted a ton of films, like “Jurassic Park,” so it could be anything from the Amazon to some mythological island at sea.

With Hawaii, I was thinking about the landscape as a character unto itself of multiple temperaments because the island is fused by multiple volcanoes that have different life spans. The landscape looks very different at different times. Some of it certainly looks like it could be another planet and I thought about that a lot with regards to Hawaii. We are here on Earth, trying to make this relationship relating to another place that may have been discovered or is from the past. That’s certainly the theme throughout the whole film — that we are looking at the past to see where we are in the present even if we are dealing with technology that is going to be built in the future.

WSN: Two things came to mind. In a previous interview, you’d made this comment about how the lava itself occupies its own space and, in its own way sort of way, colonizes space with its own wild rhythm. And regarding mythology and how Hawaii is mythologized, another person that becomes this vessel by which the culture is mythologized is Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, who appears multiple times throughout this film. I was wondering whether you could talk me through Johnson’s place in this film and what you make of this Hollywood figure working through such a subversive film?

FS: It’s funny, part of me actually really loves The Rock, although I do not identify with his level of masculinity. In terms of popular culture, I don’t know if you’ve seen “Jumanji,” but it’s a film that deals with identity and intolerance. I think anyone from anywhere who watches “Jumanji” could understand that we should tolerate one another if we change from one identity to another. I’m giving “Jumanji” a lot of credit, but I mean, everybody’s watching that film and it’s talking about identity when a lot of films aren’t.

The Rock, who I want to think is a really great guy and I do love, and although he didn’t say very much, did show up to the protests and Mauna Kea, and that made, in itself, a big difference because he has millions of followers. Because it seemed like he cared about Mauna Kea, a lot of people suddenly did. It gave it a lot more attention.

I was interested in thinking about The Rock’s identity in popular culture being related to Hawaii because he embraces it so heavily. I mean, he’s playing King Kamehameha in “The King” and it’s really tricky to think about what that’s going to look like because we’re talking about Robert Zemeckis directing it and Randall Wallace, the guy who wrote “Braveheart,” developing the script. This is going to be an insanity. Hawaii’s identity has been suppressed in so many ways through cinema and tourism fictionalizing this location and forcing it into an Americanization. I’m interested in talking about all of these things in order for people to really realize the absurdity of it all.

WSN: You mentioned wanting to see film as a point of inquiry and you mentioned “Jumanji.” A lot of people are seeing it and perhaps having these same thoughts about identity, but my worry is that where your film might open up to viewers to research, films like “Jumanji” and “Jungle Cruise” might lead general audiences to a void of thought. Is it the form of your film that elicits inquiry or the form of these other films that inhibits it?

FS: Although I do think of cinema as a point of inquiry, as if there’s just this one point, there are multiple points. I can dig from the history of Polynesian voyaging to the arrival of Christian missionaries to the first arrival of foreigners and then start talking about astronomy. Those are four points that have all of these relationships. These four points branch out and move all over the place, and I think people are really tied to creating a direct narrative with a plot to wrap all of these connections up, even in nonfiction filmmaking. I think that moving away from that could be way more informative and add a little more activity in terms of the viewer.

I’m always watching and listening to a lot of pop films and music because I know it really informs the status quo, but there’s a way of understanding how everybody is operating based on pop and there’s always a way to dissect that. I think of nonfiction filmmaking as these moments of memories, memories that you put together rather than try and fake into a narrative.

WSN: There’s an image toward the beginning of your film highlighting all these different constellations, and I think that’s a very good image that boils down what you were saying about having this one frame by which multiple points disperse themselves into several ideas. My question to you is, how do you manage to balance all these ideas?

FS: I always approach a project with a conceptual idea that’s written down. Arriving with this conceptual idea and with all this research, I approach the production and the post-production process like the whole night sky of constellations. Then, my peripheral vision starts to get a little bit smaller as I try to narrow things down while not being fully in control because I know once I’m there, things are always ever-changing.

For example, with Hawaii, I went insane researching as much as possible, reading all of these diaries, memoirs, legal documents — just everything imaginable — but I know there’s still more. I understand that we have specific connections to particular moves, conventions and strategies, and so I think about how that might work and how that might be exchangeable. In terms of shooting, simply speaking, in terms of dealing with framing strategies, what a close-up might do or how it might work in relation to an establishing shot elsewhere informs how that can be interchanged over and over and over again.

I’m thinking about this film as a puzzle that doesn’t have these specific pieces. It has multiple sides to which each piece could fit into, while also sliding into other sides and connecting with other pieces, if that makes any sense? We’re dealing with the same picture, there are just multiple combinations.

WSN: We have a lot of aspiring young filmmakers at NYU. Do you have any advice for them?

FS: There’s so many phases when it comes to getting into making films and then making films. Never lose sight of the purpose. It’s very easy for people to be surrounded with people who lose sight of the love and interest of making a film because they’re seeking all of these external rewards, like “When and where will my film play?” But what I think is important about filmmaking is that you always think about the internal reward and you don’t let the external rewards get in the way. If you’re able to have that internal reward and think about it while working on something you really care about, you’ll always be happy and your practice will grow.

Contact Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer at [email protected].