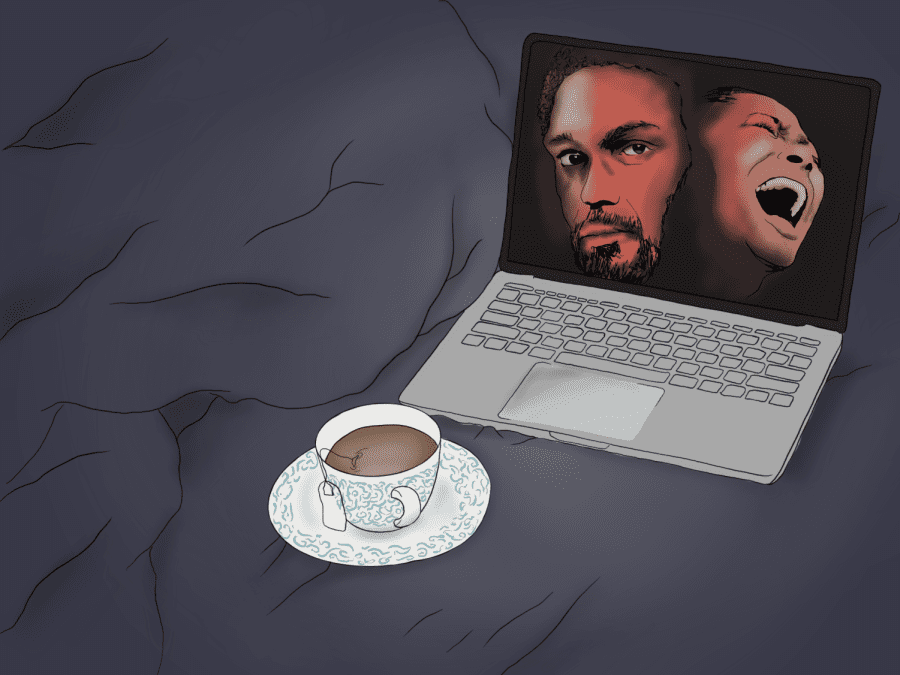

Off the Radar: Black vampire myths and addiction in ‘Ganja & Hess’

Off the Radar is a weekly column surveying overlooked films available to students for free via NYU’s streaming partnerships. “Ganja & Hess” is available to stream on Kanopy.

“Ganja & Hess” is available to stream on Paramount+ and SHOWTIME.

November 4, 2022

“Ganja & Hess” (1973) opens with a somber, gospel-inspired opening song that cryptically refers to crucifixion and blood thirst. A set of intertitles introduces the protagonist, Dr. Hess Green (Duane Jones), and immediately spells out his dark and twisted fate. Director Bill Gunn’s surrealist vampire thriller is a landmark of independent Black cinema and a singular entry in the canon of horror fiction.

A lavish upstate mansion decorated with fine art and ancient relics from the African continent serves as the backdrop for Gunn’s examination of the corruptive social elements that plague his community. Green, a rich anthropologist, is studying an ancient African culture called the Myrthians, a civilization that feasted on human blood. One night, his mentally unstable research assistant, George Meda (Bill Gunn), stabs him three times with a Myrthian dagger and subsequently takes his own life with a gun.

When Green awakens, he is surprised not only to find himself alive, but also to have developed a newfound need to drink blood. Green’s character arc displays the degradation of humanity in the face of addiction — a confident and affluent intellectual succumbing to the moral abyss. Initially, Green tries to control his bloodthirst; he only preys on those he deems the lower strata of society — criminals, prostitutes and pimps. However, as the narrative progresses, the forces of addiction override his moral principles.

This psychosexual horror is enhanced by its crude and deeply unsettling score. Composed by Sam Waymon, brother of famed singer and civil rights activist Nina Simone, the soundtrack of this film incorporates a “mixture of soul, tribal chants, gospel and trippy, dissonant experimental cues” that gives the film a constant feeling of otherworldy psychological distress. The jarring musical elements, coupled with the varied and frenetic camera work, culminate in a shock-inducing cinematic experience.

Aside from its innovative play on traditional tropes within the American school of horror films, “Ganja & Hess” is also important in the discussion of the politically ebullient Blaxploitation film movement that revolutionized Black Cinema in America during the 1970s. Blaxploitation featured Black-centric films, from directors like Melvin Van Peebles and Gordon Parks Sr.

Films associated with this movement were immediately controversial within the Black community, and America at large, for their mixture of transgressive content alongside radical politics. The NAACP claimed that the genre was responsible for perpetuating racial stereotypes and “proliferating offenses” against Black Americans.

Despite Blaxploitation’s negative reputation among general audiences, films like Gunn’s “Ganja & Hess” proved the genre as an effective mode of addressing the political reality of Black America in a stylized manner. Gunn’s fear of addiction in the Black community would indeed manifest a decade later in the deadly opioid epidemic. Fifty years later, a destructive drug culture still permeates throughout Black culture.

Even Green embodies the detachment between different classes in Black society. His apathy toward the urban underworld highlights the divisions and prejudices that are attached to Black identity. Blaxploitation films may not conform to the ideology of mainstream political groups, but they play a key role in expressing Black issues and featuring Black talent on the silver screen.

Contact Mick Gaw at [email protected].