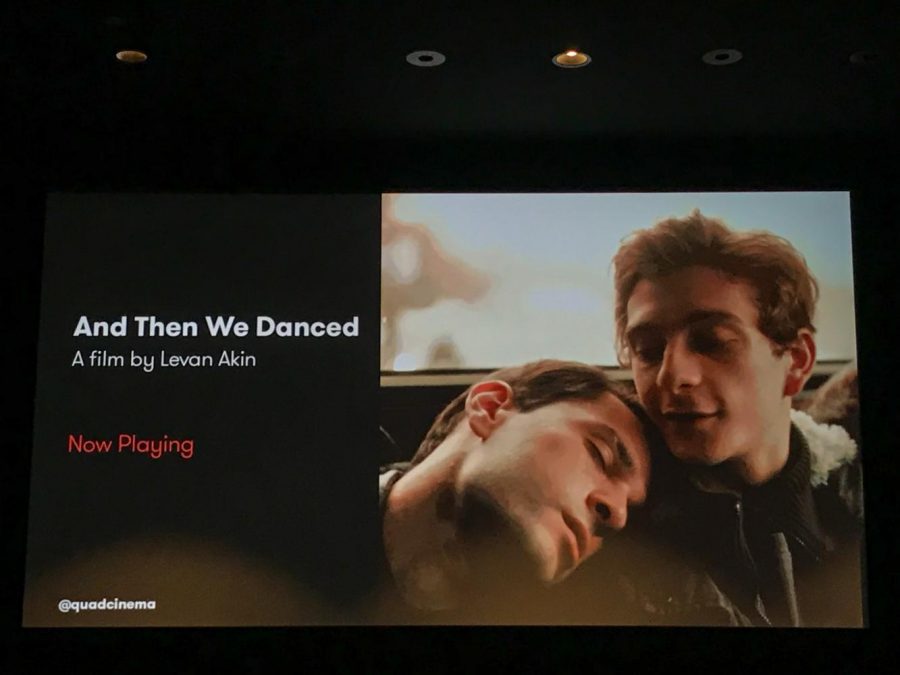

Sweden’s Oscar submission opened to buzz at the Cannes Film Festival, but in Georgia, the country the film is set in, it opened to intense protest. Due to the LGBTQ+ content of the film, many ultra-conservative nationalist groups saw the movie as immoral. They protested at the theaters and threatened moviegoers over the three days it played in Batumi and Tbilisi.

“I made this film with love and compassion. It is my love letter to Georgia and to my heritage,” stated Director Levan Akin in response to these threats on his Facebook. “With this story, I wanted to reclaim and redefine Georgian culture to include all not just some.”

The film follows Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani), a traditional Georgian dancer who has been training since he could walk for a place in the National Georgian Ensemble. When a new dancer arrives, Irakli (Bachi Valishvili), he feels both envy and desire for him. It leads him to discover the inner freedom and rebellion that lies in both his dance and himself.

23-year-old newcomer Levan Gelbakhiani is where the heart and soul of this movie lies. His performance erupts with subtle beauty and passion. The glances he gives throughout the film’s silences perfectly convey the fight going on in his head. Is he jealous of this new dancer or is he feeling a yearning for him? Both are present in just the looks he gives, and this duality of emotion exists throughout the entirety of his delicate performance.

Where the film and Gelbakhiani shine most is in the dancing. Gelbakhiani dances with both power that demands your attention and softness, which the headteacher in the film criticizes, saying, “There is no room for weakness.” The dancing in the film serves as a way to communicate things that are impossible to put into words. Gelbakhiani is masterful at using such calculated and fine movements to transmit what he is trying to say directly to the audience.

The more the film progresses, the more freedom comes into his style, and by the end, Merab is a very different dancer from where he started, perfectly mirroring his sudden awakening to his identity and self-acceptance. It also emphasizes the message of the film that — while one can be proud of their heritage — they can still allow current ideals to affect and shape them, blending tradition and modernity in both dance and values. The final dance at the end of the movie is one of the first awe-inspiring movie moments of the year. It is undoubtedly a moment that will stay in the mind long after the screen has gone dark.

The only significant issue with “And Then We Danced” is the overly-packed screenplay. The film is well-written, and the dialogue has intention, but at times it feels like too much is said. Sub-stories are a bit too emphasized instead of just allowing the audience to make their own inferences. The main beauty of this film lies in what is unsaid, in the way people find ways to communicate without words, so one almost wishes the film would cut down on some of the side stories to allow more of those moments to break through.

“And Then We Danced” is both an understated and forceful film that is deliberate in the political message it presents. One can tell that Akin fought to get this story told, and the issues in the film are dealt with purpose and grace. This film is profoundly moving and has an urgency in it that cannot be ignored. This film is truly a love letter to Georgia as it shows Akin’s passion for his heritage as well as the desire for the nation to become a more accepting place.

“And Then We Danced” opened February 7, 2020, and is playing at the Quad Cinema and The Landmark at 57 West. It is being shown in Georgian with English subtitles.

Email Kaylee DeFreitas at [email protected].