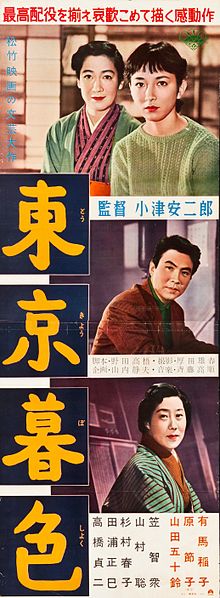

Yasujiro Ozu’s “Tokyo Twilight” (1957), restored in 4K at Film Forum on Houston Street, documents the simultaneous evolution of the Sugiyama family and the eponymous Japanese city on the eve of a modern era of urbanization and industrialization. Two sisters, the older, unhappily married Takako (Setsuko Hara) and the college-aged Akiko (Ineko Arima), grapple with the reentrance of their mother into their lives after a lifetime of absence, while their father Shukichi (Chishu Ryu) observes his daughters’ growing independence and changing sense of direction.

Ozu’s final black-and-white film is not only a portrait of a family in decline but a city in limbo, trapped between a feeling of nostalgia and the dawn of a new age. Interspersed in the narrative’s transition moments are small snippets of train stations, cafes and urban side streets which present a twilight scene of Tokyo, a place which parallels the nature of the sisters’ despair. The opening shot — a still of an industrial high-rise juxtaposes a sky crisscrossed by wires — is of the cityscape, not of the family, highlighting Tokyo’s metaphorical significance in the film. The heaviness of gray steam foreshadows a sense of bleariness and fatigue echoed by the father’s silhouette of hunched loneliness.

Like the quality of the black-and-white film stock, the acting performances feature a gradient scale of shifting emotions. Characters take their time in conversation, the actors careful to show the internalization of a previous remark before reacting with a thoughtful expression. Pauses in dialogue can feel overly ponderous, especially on the part of Shukichi, whose deep introspection counters frequent scenemate Takako’s casual detachment. Hara’s performance appears guarded and unreadable at times, which, while at first off-putting, demonstrates a difficult restraint to hide the pain she feels for her troubled sister and the obliviousness of her father.

Akiko is the most emotionally transparent of the ensemble, as she exhibits the impact the childhood trauma of her mother’s absence has caused her. This difficult past haunts Akiko as she deals with current problems: the neglect of her former lover and an unwanted pregnancy. The stress of the situation gradually affects Akiko’s posture and ability to think rationally. The visceral physical transformation the character takes demonstrates masterful acting on Arima’s part.

While slowed-down interactions seem tedious, watching for the tension between modernization and tradition provides the story with a heightened sense of anticipation. A stark contrast is visible in the juxtaposition of settings, particularly as Shukichi moves through his daily life: from his classically designed Japanese house to the cold, impersonal bank where he works, and then to a restaurant specializing in traditional eel cuisine, where the hostess wears a kimono.

As in “Tokyo Story” (1953), Ozu’s other renowned work set in the city, a sense of melancholy due to the fleeting quality of time is felt through generational distance, the root of the profound sadness in the film. Shukichi repeatedly questions his daughters’ happiness in their relationships, unable to understand that their arranged courtships go against an emerging ideal of choosing a partner for love instead of for financial or social benefits. The dissonance is summarized in a recurring passing statement: “Young people these days are impossible to figure out.”

“Tokyo Twilight” is a bit like a novel that takes some time to read, but it’s worth it to hold out on judging the film based solely on tempo. Layers of imagery and visual metaphor lie beneath the script, presenting nuanced shades of change.

Film Forum’s series “Shitamachi: Tales of Downtown Tokyo,” runs from Oct. 24 – Nov. 7 and features films by directors including Ozu and Akira Kurosawa. “Tokyo Twilight” runs Nov. 7–14 in a new 4K restoration.

A version of this article appears in the Monday, Oct. 28, 2019, print edition. Email Alexandra Bentzien at [email protected].