I spent more time trying to make up my mind on how I felt about “Ocean Blue” than I spent actually watching the film. The Carol Morley-directed flick is an adaptation of the Martin Amis novel “Night Train,” chronicling veteran detective Mike Hoolihan’s investigation into the murder of an esteemed astrophysicist. The main difference between the two works is that Amis’ book is a comical parody of detective fiction. “Out of Blue” takes itself too seriously, going all in on its chilling atmosphere, but making its inclusion of the numerous parodic elements found in the source material feel pretentious and cliche.

For a narrative that requires a character-driven focus, the film does a very lackluster job of developing an interesting cast. Hoolihan (Patricia Clarkson), the protagonist, is a decidedly stoic character who rarely divulges information about her past. The idea that she isn’t a compelling protagonist makes sense based on her characterization, but from a narrative standpoint, it just ends up shackling the audience to the perspective of a character to whom they have little attachment.

Other characters don’t fare much better than Hoolihan, with most of them spouting inorganic dialogue that quickly dissipates into little more than a persistent droning on the screen. The several philosophical monologues littered throughout feel vaguely smug as well, as though the movie is patting itself on the back for its own superficial intellect. A few of the characters manage to get a smartly written line out every once in a while, but those instances only illuminate the rest of the script’s faults. Despite the film’s persistently serious tone, it manages a few welcome moments of dry comedy that liven things up just a tad and remind the viewer that this movie was, in fact, based on a parody of the detective genre.

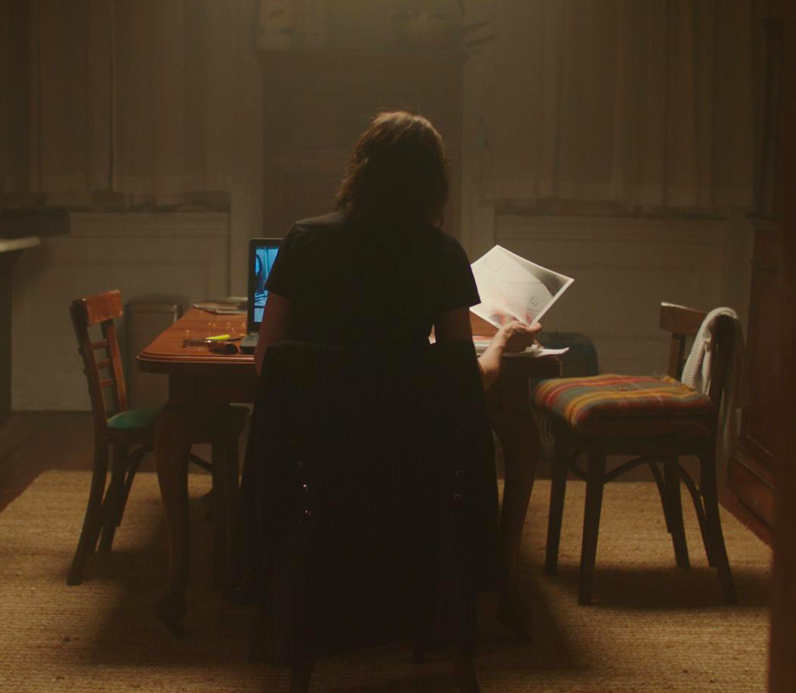

Moving past its narrative flaws, there’s actually quite a bit to respect about “Out of Blue” as a general experience. The film makes great use of its visual palette, as the cold blues befit the narrative’s lonely, existential focus. The sound design is excellent as well, keeping the viewer on edge with unexpected moments that pierce its own intimate silence. These elements, coupled with off-kilter editing and a muddled narrative, make “Out of Blue” almost feel like a dream. It barely makes sense, but it makes you feel something all the same.

The most important thing to understand about “Out of Blue” is that you should not watch it for the story. Filled with confusing characterization and bizarre sequences, the movie attempts to dress its relatively simplistic mystery in so many layers of ambiguity that it nearly defies comprehension. Instead, you’re here for style more than anything else. Once you start to accept the movie as little more than a two-hour trip-fest, it’s a lot easier to digest and enjoy.

Email Ethan Zack at [email protected]