Kleber Mendonça Filho often uses his camera to spotlight the displaced and the forgotten. Whether it was in his critically acclaimed debut feature “Neighboring Sounds,” or the 2019 Cannes Jury Prize winner “Bacurau,” Mendonça depicts people and places left in the dust with the burden of an uncertain future ahead. An expert in melding the world’s rich cinematic imagination and harsh political realities, Mendonça is one of the boldest filmmakers working in the industry today.

In Mendonça’s latest documentary, “Pictures of Ghosts,” the subject is the medium of cinema itself. Having initially made its North American premiere at last year’s New York Film Festival, starting today, the “Pictures of Ghosts” will be playing at the Lincoln Center of Performing Arts. While the documentary is primarily a meticulous examination of moviegoing culture through surveying the abandoned cinema houses in the Brazilian city, Recife, it is also a deeply personal account of Mendonça’s own journey in the world of film. Archival prints are juxtaposed with present-day footage of his hometown, not as a lamentation for a bygone era of film culture, but as an acknowledgment of cinema’s constantly shifting landscapes.

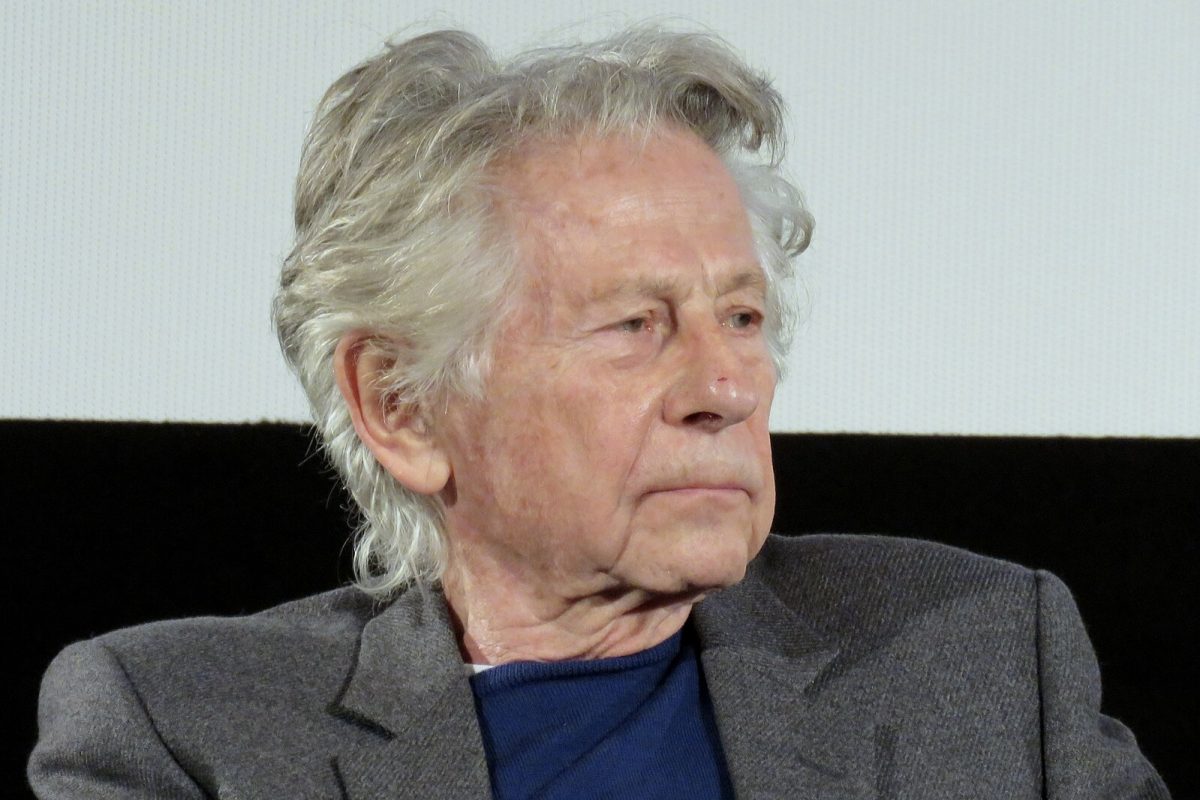

WSN sat down with Mendonça to talk about the making of his new film, nostalgia for Recife theaters, the global domination of “Barbenheimer” and the ever-changing demands of the industry.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WSN: In making “Pictures of Ghosts,” how did you approach musicality and song selection?

Mendonça: It’s not so different from casting work. It’s like finding humans to appear in the film. Music carries quite a lot of emotional and cultural weight, and it also carries an idea of time. And it should always interact with the film in an organic way.

I often — since the very beginning of making videos — could tell that once you add a piece of music to the film, you can simply tell if it is interesting, or if it is completely uninteresting, it doesn’t work.

I just wanted to end the film with myself coming out of work at night and catching a taxi, and the taxi would play “Rise” by Herb Alpert. And at some point, I would ask the driver to raise the volume, and I would look out the window and see the drugstore. I was actually worried that after so many years thinking about this song, and having made all the contacts to buy the song, I was worried if it would work. And once we added the song to the timeline, it seemed to work very well. So it really works through association, my own personal association with the song, my own relationship to the song, but also to the way it sounds.

WSN: A lot of the film seems to have come together in post-production. How did the editing inform or consolidate your ideas for the documentary?

Mendonça: During the process of planning the film, maybe six years ago, I posted a picture I found of the Veneza Cinema on my Instagram account … I think there were over a thousand comments. I could tell that this place had the same impact on myself as it had on so many other people. So I thought that it would be an important scene. I did not really write anything before I went to the location to shoot, I just shot the hell out of it. And then later, I found 35 millimeter film of the grand opening of the Veneza. So everything came together because now I have very well-shot images that photograph time.

So in terms of the ideas I kept having, they really came alive in the editing process. I have been very lucky to find a group of people who can work outside the industry standards. Filmmaking does not have the logic of a taxi meter that you start and stop. Otherwise the film would be too expensive to make. But, of course, we find some kind of agreement, and then we work together and it takes quite a long time.

WSN: In the film you feature a local cinema originally built by Nazi Germany. As a filmmaker, how do you grapple with the darker facets of your craft?

Mendonça: We all know what happened to Germany in the ’30s. It was all part of using cinema as soft power, and to build something which later would become extremely sinister in Europe. But of course, a lot of the other cinemas were bankrolled by Hollywood studios. That was also soft power, I just think that the Americans did it in a more entertaining and more interesting fashion. When you look at “Casablanca,” it is a propaganda film, but there are so many other things — it is a film — it is a beautiful film. Even when you see footage from the opening night of the Veneza Cinema in my film, it was a Universal film that was screening. It’s all part of politics. You see the governor coming in and they had a pretty good idea of how much money that place would generate in the coming years.

So you kind of have to deal with politics, but also market behavior. For example, this film was screened mostly in the wonderful art houses in Brazil, but we burst a bubble here and there, showing in bigger theaters like Cinemark. They had previously done a great job with my other films. But with this one, they kind of buried it. Maybe because it’s a documentary? You know, in July, we had “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” taking up like 90% of commercial screenings in Brazil. It’s crazy. It’s unacceptable. You cannot go to a multiplex with 15 screens and realize that all of them are screening two films. I think the “Pictures of Ghosts” is also very much about that. It’s very much about cinema and not only as a memory but also as a product because a lot of these cinemas were shop windows. They were places where films were sold. A place where ideas and ideology were sold.

WSN: Your film is very localized and planted in the theaters of Recife, but it also comes at a very transformative time in cinematic history. Did you always see the decline in moviegoing as a universal phenomenon?

Mendonça: Always. It is a universal phenomenon because the film industry — particularly Hollywood — has turned the world into its own home. All the decisions made in Los Angeles, they will somehow impact us. Some people in Brazil think the film is about a local phenomenon, but it’s happened everywhere. [The film] happened in Montpellier, Sydney, Winnipeg, Mexico City — it was just a global phenomenon. It’s also really about technology. In the ’50s, television arrived, and then there was Cinerama, CinemaScope, and then VCRs in the ’70s, cable television, DVDs and then streaming. We are always reacting to how we access images.

Hopefully the film is very much an observation on history, and not some kind of whining about how things used to be so much more interesting. It’s just an observation on how things change, and how we have to deal with it.

Contact Mick Gaw at [email protected].