Since the announcement of “Sunrise on the Reaping” in June, I have been eagerly awaiting the arrival of my pre-ordered novel, ready to dive right back into the nostalgia-inducing series of “The Hunger Games.” As an avid fan of both the books and films, my expectations were exceptionally high going in.

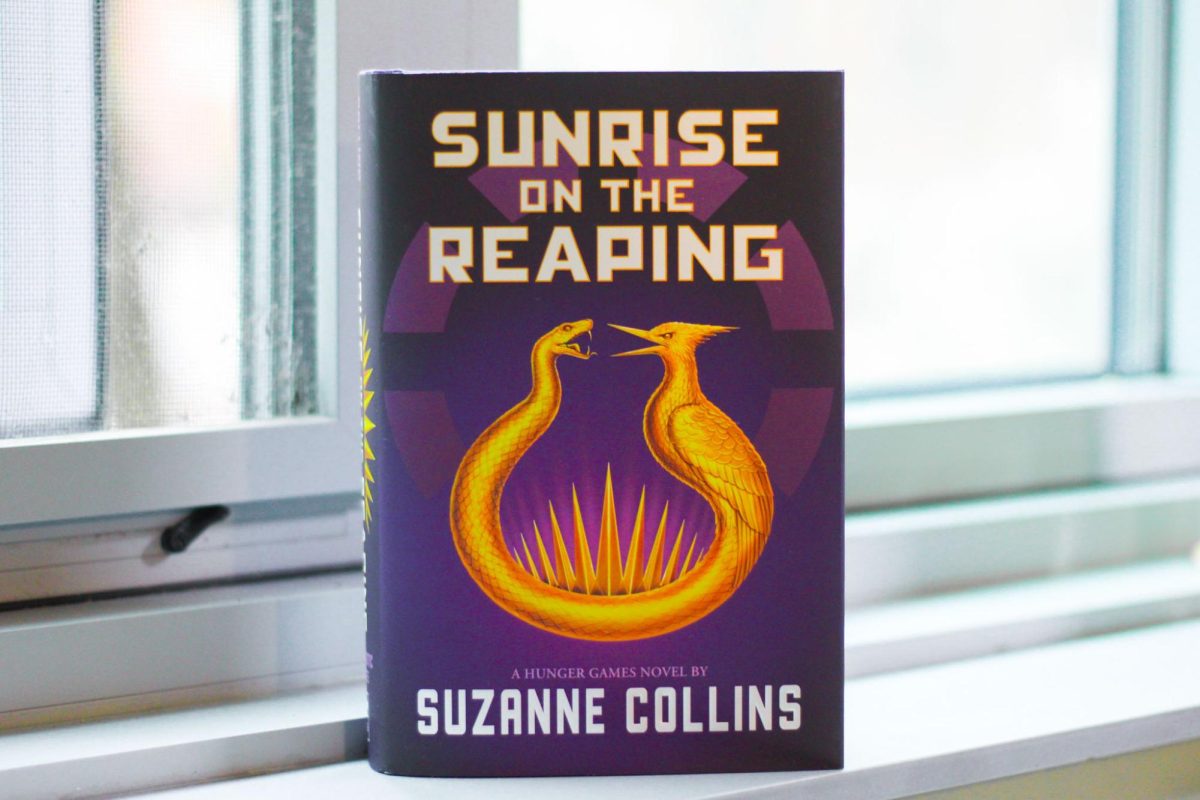

As the newest addition to Suzanne Collins’ beloved series, “The Hunger Games,” this novel, released on March 18, is the second to prequel the original trilogy, following the 2020 release of “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes.”

The dystopian universe that Collins crafted is set in the post-war, North American nation of Panem. The first novel in the trilogy, takes place in the year of the 74th Annual Hunger Games and following the perspective of Katniss Everdeen, sparked the worldwide success of the franchise. “Sunrise on the Reaping” follows Haymitch Abernathy, the District 12 mentor in the trilogy as he wins the 50th Hunger Game.

Following a similar timeline as the first “Hunger Games,” the book begins on the morning of the reaping ceremony, when the two kids from each district are called from a lottery to be in the games. However, in the 50th Games — a milestone anniversary known as the Second Quarter Quell — there are special rules, and the number of tributes from each district is doubled. Opening with the detail that Haymitch’s birthday falls on this same day, Collins takes us through the 16-year-old’s routine as a provider for his widowed mother and ten-year-old brother. After a disastrous reaping ceremony, Haymitch becomes one of the four tributes sent from District 12. His narrative is filled with loss, suffering and calculated retaliations against the Capitol — laying the foundation for Katniss later to lead the inevitable rebellion in the districts 25 years later.

One of the most apparent questions with a prequel’s release is its ability to stand alone. Though I’ll admit that reading the original trilogy will foster a deeper appreciation for details that Collins includes, I don’t think only reading “Sunrise on the Reaping” would hinder most readers’ understanding of the overall plot. While Collins does reiterate a lot of critical elements of the “Hunger Games” universe — muttations, the Quarter Quell, the process of the games — the intricate connections between this book and the others truly made it infinitely more memorable.

Any aspect of this fictional world is nostalgic enough on its own for those who grew up reading them, but the familiar names and symbols that Collins weaves throughout the novel had me flipping through the pages to find out more about these beloved characters. Beyond telling Haymitch’s backstory, this novel fills gaps of knowledge between the first prequel and the original books. Collins’ use of first-person narrative allowed for an intimate account of Haymitch’s journey in surviving the games and the events subsequent to his victory. We are finally given an explanation of Haymitch’s cranky, morose character introduced in the first book in the prequel of the trilogy, as well as his connection to the rebellion. This novel bridged these gaps seamlessly in a way that the third-person account of “The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” failed to do in a satisfying way.

What made this prequel so timely was the renewal of Collins’ political critiques. She opens this book with four quotes that set the scene for themes of censorship, propaganda and rebellion which she confidently floods the book with. Political criticisms tactfully placed in the other novels are much more explicit in this book, from the reaping day being on July 4, to the Capitol’s exploitation of kids for mass entertainment and its use of the games to exert control. Haymitch acts out these themes smoothly from the very beginning of the book, when he decides at the reaping ceremony — by minimizing the emotion he shows while parting from his loved ones — that he will not give the Capitol the satisfaction of making a show of his suffering.

The use of censorship is illustrated neatly in a scene following Haymitch’s victory, during an interview in which they replay the footage of the games. Haymitch realizes that the tape shown to the audience was an edited version of what actually happened in the arena. With this, many of the rebellious actions he took to disrupt the gamemakers and dismantle the arena itself were not seen by anyone outside the games. In diluting Haymitch’s efforts to spark a rebellion, the Capitol turned the 50th Games into more propaganda in support of its continuation.

These pivotal themes that Collins has drilled into the series were clear-cut in her second prequel, as readers are given a first-hand account of the extent of the Capitol’s censorship in regards to what happens in the Hunger Games arena versus what the audience sees. Illustrating that talks of a rebellion against the Capitol were happening well before Katniss’ time, Collins actually reveals the depth of the Capitol’s power in thwarting an uprising. Haymitch’s spark of rebellion that was quickly diminished, eventually becomes the blaze that is Katniss Everdeen’s dismantling of the Capitol.

Contact Eva Mundo at [email protected].