With “Her Body and Other Parties,” Carmen Maria Machado established herself as a writer of inimitable talents. In her memoir, she brings all the same cards to the same table, but this time, it’s personal.

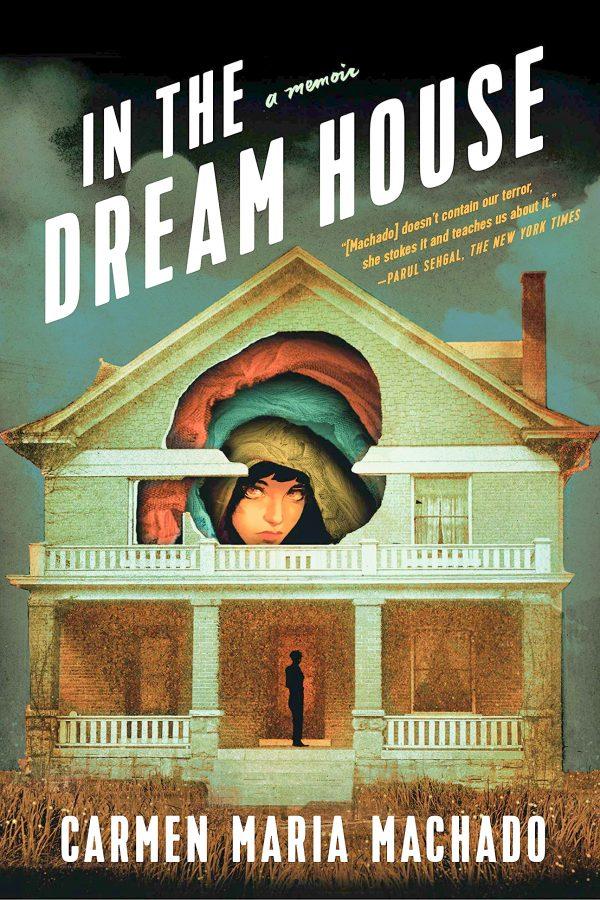

“In the Dream House” recounts a past relationship which was both verbally and physically abusive. The abuser is referred to as “the woman in the dream house.”

Machado is hyper-conscious of the implications of telling such a story. “If your family found out,” she writes, “they’d probably think it proved every idea they’ve ever had about lesbians, and you wish she was a man because then at least it could reinforce ideas about men.”

She draws from queer studies, weaving criticism and theory into the narrative, and meditates on popular depictions of domestic abuse in film and literature. She cites legal cases in which women were presumed to be incapable of abusing a partner, or in which a queer jury member was hesitant to convict another queer woman, despite evidence that this woman had been abusing her partner.

She references Saidiya Hartman’s idea of “archival silence” in reference to queer stories of domestic abuse. She also cites Louis Bourgeois who writes,“You pile up associations the way you pile up bricks. Memory itself is a form of architecture.”

Architectural metaphors abound. While we typically think of a dream house as a symbol of domestic bliss, Machado refigures it as a place of confinement, and in doing so, destabilizes our understanding of the word dream. While it might commonly be understood to mean ideal or fantasy, in Machado’s memoir, it comes to mean something more like phantasmic.

In “Dream House as Inner Sanctum,” she discusses the preciousness of interior spaces that are all our own, such as the four-walled refuge of a childhood bedroom. She recalls when, as a child, her father removed her doorknob as a punishment.

“When the door was opened, nothing happened,” she writes. “It was just a reminder: nothing, not even the four walls around my body, was mine.”

A sense of Machado’s isolation from herself persists throughout the book. All of the narrations of her experiences with her abuser — which take up the majority of the book — are written in the second person, a subversive choice of point of view for a memoir. But of course Machado’s memoir is anything but traditional. In her use of the second person, Machado both draws us into the story and displays a chilling disavowal of her experience. It is something that happened to some other person, some past version of herself that she cannot own.

If the story titled “Inventory” in “Her Body and Other Parties” was an inventory of sexual partners, “Dream House as Inventory” is an inventory of Machado’s vices and shortcomings. If her short story was a study in pleasure and in communion, her memoir is often a study in self-loathing, and how one person can teach another how to self-loathe with gusto.

Her sensual nature, here, becomes a source of shame. “You’d rather have an orgasm than do most things,” she writes in this litany of everything wrong with her. “The only way you can focus during prolonged meditation is to think about an orgy.”

Machado is often funny, such as when she describes her adolescent religious fanaticism, writing, “When other teenagers were figuring out what good and bad relationships looked like, I was busy being extremely weird: praying a lot, getting obsessed with sexual purity.” And yet the grain of truth beneath such admissions — she didn’t learn what distinguishes a good relationship from a bad one, a healthy one from a non-healthy one — is devastating.

Many of the fragments filter the dream house through various genres. To name a few: stoner comedy, cautionary tale, American gothic, bildungsroman, soap opera and lesbian pulp novel. She explores, with a scholarly tone, the limitations of some genres; the American Gothic is, for example, heteronormative by nature. Other times, she uses the genre label to characterize the story being told. In “Dream House as Sci-Fi Thriller,” for example, she describes falling asleep on a friend’s couch and waking up to an inbox full of infuriated voicemails from her girlfriend.

And then there is the project of the book, which is dream house as memoir. The memoir itself is a house, each fragment a building block, that we experience piece-by-piece but whose power we cannot fully register until stepping away, admiring the gestalt.

In “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure,” Machado asks the reader to pick a response to her abuser chiding her for moving around all night and keeping her awake. Options include, “If you apologize profusely, go to page 163,” and “If you tell her to calm down, go to page 166.” The book becomes a puzzle, one which always leads us to the same conclusion.

Through all the playful manipulations of form and essayistic digressions, Machado manages to tell a story: one of a loss of one’s self, as she falls into the traps of her abuser.

And we are along for the descent. Her early descriptions of her abuser are imbued with all of the infatuation of a new relationship. We see how she was blinded; we are blinded ourselves.

“You’re not allowed to write about this,” her girlfriend says to her after one fight. “Don’t you ever write about this.”

In writing about it, Machado brings it into being, fills an archival silence. She builds the dream house so we can step into it and explore all of its dark corners and haunted corridors.

“In the Dream House” will be released Tuesday.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, Nov. 4, 2019 print edition.

Email Julie Goldberg at [email protected].