Halloween is approaching, and one literary legend may be rising from the dead.

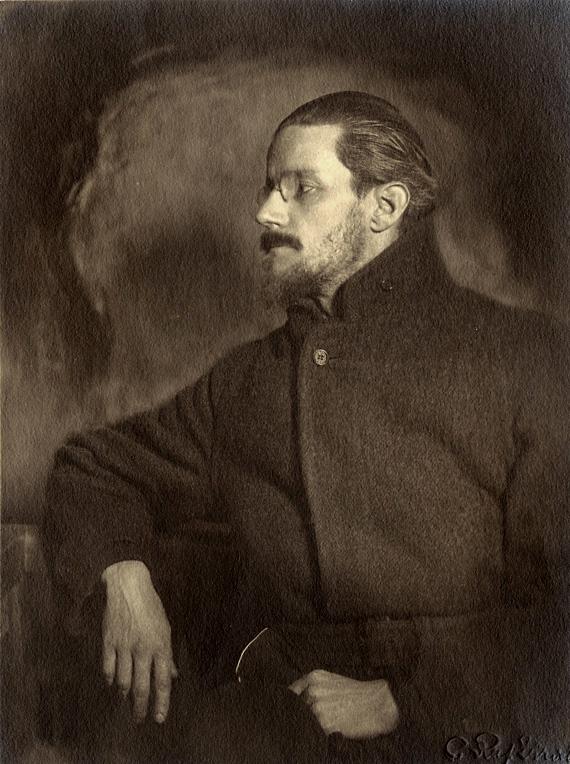

To be relocated and reinterred, that is. James Joyce is currently buried with his wife Nora Barnacle at the Fluntern Cemetery in Zurich, Switzerland, where he spent the final years of his life. But Dublin city councillors have proposed a motion to repatriate Joyce’s remains — that is, move them from Zurich to Dublin. Barnacle’s remains would also be transferred.

The councillors are calling for the lord mayor and chief executive to write to the Minister for Foreign Affairs, and while the motion was passed on Oct. 13, a number of hurdles would need to be conquered before Joyce’s body could actually be repatriated. The first of these would be the cooperation of the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Like many Irish writers, including Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw and Samuel Beckett, Joyce spent much of his life away from his birth country. The last time he visited Ireland was 1912, a full 29 years before his death in 1941. Since 1904, he had been living abroad in Trieste, Paris and Zurich.

Wilde and Beckett are both buried in Paris, while Shaw rests at his home in St. Lawrence, England. Another Irish writer, Maeve Brennan, spent the greater part of her life in the U.S. as a writer for The New Yorker. Her remains are buried in Queens.

Of course, Ireland acted as the backdrop to much of Joyce’s writing and informed his greatest works of literature. When asked towards the end of his life if he would ever return to the country, he said, “Have I ever left it?”

“If you want to find James Joyce in Dublin you can, through his works,” NYU Professor and Irish Studies scholar Dr. John Waters told WSN. “At no point, ever, did he express any desire to be buried in Ireland.”

What Joyce did express was a continued pull toward or at least an interest in Ireland, even as he took up residence abroad. When he lived in Paris, he allegedly loved to quiz visitors on Dublin geography, asking them to name shops and pubs on various streets.

Brennan similarly looked for signs of Dublin while living in New York City, sans the cross-examining of bewildered tourists. Noting a three-cornered shadow on the pavement on 42nd Street, she wrote, “It was exactly the same shadow that used to fall on the cement part of our garden in Dublin, more than fifty-five years ago.”

For Joyce and Brennan, Dublin was inescapable. But that doesn’t mean it was where he wanted to rest for eternity. Through his life, Joyce had a fraught relationship with his home country.

Under the influence of the Catholic Church, Ireland was wary and censorious of Joyce’s writing.

“Ulysses,” the writer’s crowning masterpiece, was effectively banned — it was never imported into the nation at all, for fear of repercussions.

When Joyce attempted to publish “Dubliners” with Maunsel & Co., the process was repeatedly suspended due to concerns over public reaction to the purportedly obscene and anti-Irish stories.

“His final resting place in Zurich testifies to his life of voluntary exile and his search for artistic and intellectual freedom,” Waters said. “He pursued that outside of Ireland because the Ireland of his youth denied it to him.”

Ireland is now eager to claim Joyce as their own, and the timing of the council’s motion is certainly dubious. The councillors are set on bringing the remains back to Ireland before the 2022 centenary celebration of the publication of “Ulysses.” It follows that they may be motivated primarily, if not entirely, by mercenary concerns.

“The repatriation of the bodies of James Joyce and Nora Barnacle is only being proposed because of a belief that it will contribute to literary tourism in Ireland,” Waters said.

Fritz Senn, founder and director of the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, believes the Swiss government would be resistant to the motion, largely due to the popularity of Joyce’s grave among Zurich tourists. “Many people go to his grave, so there would be an issue,” he told The Guardian.

Waters is in agreement with the vast majority of Joyce scholars in his belief that the Dublin City Council can honor Joyce’s memory in more productive ways.

“Whatever money Dublin City Council would devote to a Joyce grave or memorial, should be spent on the homeless and the arts and the youth mental health crisis,” he said.

NYU Professor Dr. Kelly Sullivan similarly believes Joycean commemoration should take place in the form of funding for conservation and maintenance of significant Joyce landmarks in the city.

She pointed to the house on Usher’s Island, the setting of Joyce’s short story, “The Dead,” as a prime example. When the house went up for auction in 2017, the Dublin City Council said it had no interest in purchasing it. Now, she worries it will suffer the fate as 7 Eccles St., the home of the fictional protagonists of “Ulysses,” which was torn down in the 1960s.

While Ireland arbitrarily names streets and bridges after Joyce, actual literary landmarks are often forgotten and left to rot.

“It’s a sad irony that the bridge over the Liffey connecting Usher’s Island to Ellis Quay on the north is the James Joyce Bridge, but the 1775 house where Joyce’s aunts taught music and had annual holiday parties remains in a state of disrepair,” Sullivan said.

While it is unlikely that the City Council will actually reallocate their funds in this way, it appears equally unlikely that they will be able to gain not only the approval of Joyce’s grandson and literary executor, Stephen Joyce, but also the cooperation of the Swiss government. Working with Switzerland will require active pursuit of repatriation on the part of the Irish government.

“Think you’re escaping and run into yourself,” Joyce wrote. “Longest way round is the shortest way home.” What exactly “home” was and will be for Joyce remains contested.

A version of this article appears in the Monday, Oct. 28, 2019, print edition. Email Julie Goldberg at [email protected].