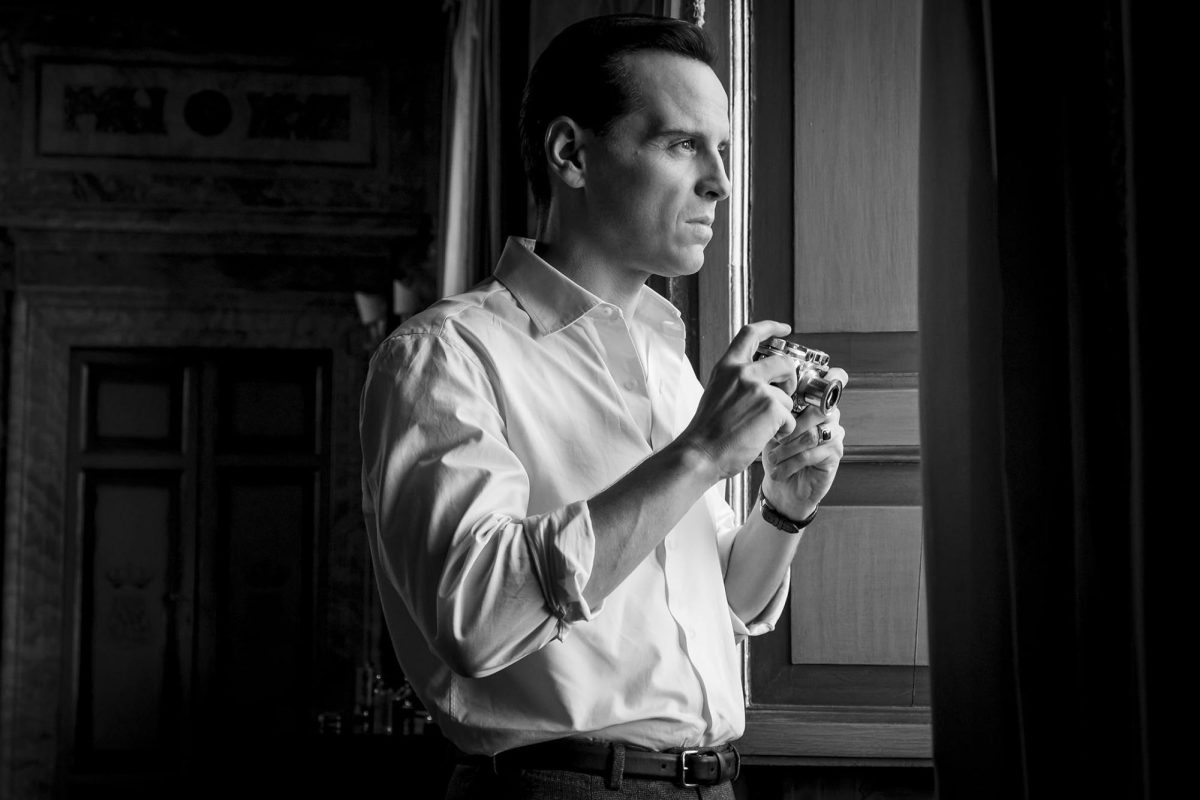

Irish actor and internet darling Andrew Scott, most famous for his portrayal of the hot priest in “Fleabag” (2016), returns to television with director Steven Zaillian’s new Netflix limited series “Ripley.” Besides having Scott’s daring eyes dazzle our screens, the noir series offers a darker spin on its 1999 counterpart, “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” Casting a matured version of its titular character, this series feels more ambiguous.

Scott stars as Tom Ripley, who runs menial debt collection scams in New York City. The small-time con artist lands his biggest gig yet, hired by a wealthy man to look for his free-roaming son, Dickie (Johnny Flynn), in Italy. Tom takes off to the coastal town of Atrani, and becomes acquainted with Dickie and his suspecting girlfriend, Marge (Dakota Fanning). As the two men bond, they eventually go on a trip that enacts a chain of events: hotel stays, murders, evasion and many lies.

Although shot entirely in black-and-white, the reimagination of the whimsical ’90s thriller shines through in its dark tones. The eeriness of “Ripley” is brought to life by the performance of the main cast. Fanning’s deadpan delivery sets the tone for Marge’s lurking confrontation. At the end of the series, Marge tensions with Tom are heightened, as she observes Tom’s odd behavior and begins to suspect that he has something to do with Dickie’s missing ring. Scott’s raw portrayal draws contrast between the con man’s facade of nonchalance, enhancing the character’s enigma in his nervous gulps and fidgety hands. Between Scott’s frowns of pretend confusion and Fanning’s forced smiles, antagonism gradually develops as their lives intertwine.

Most known for writing “Schindler’s List”, Zaillian’s adeptness in employing camera angles as motifs invites viewers to read between the lines. The film is shot though extreme high, low and bird’s eye view angles; statues, paintings and animals consistently grace these frames. The camera often pans over stoic faces directly, evoking a bone-chilling feel of surveillance. Inanimate objects are characterized to be watching Ripley carry out his scheme despite no other human character witnessing — those who do end up dead. This omniscient perspective also symbolizes premeditation on Tom’s end, and on a closer look, his fate seems predestined.

Compared to its ’90s counterpart, Zaillian’s “Ripley” sees a pessimistic tale of the con man. Themes of moral ambiguity bounce off the adoption of black-and-white filming, as opposed to the cartoonish feel of the older version. The use of wide shots where characters are proportionally smaller than their grandiose Italian backdrops gives “Ripley” the impression of a theatrical performance. Close-ups of the character’s blemished faces are mixed without cohesion, capturing realistic human tendencies while retaining a degree of artificiality.

The most notable difference between the two versions is that Tom, Dickie and Marge are middle-aged in “Ripley.” The plot moves spontaneously, just as the characters’ personalities emulate what a college-aged person would be in real life. Dickie is a wealthy playboy whose carelessness dooms him to Tom’s schemes, while Marge is portrayed as an innocent bystander. However, Zaillian’s choice of aging the characters adds layers to their psyche. Dickie may be rich, Marge may be innocent and Tom’s ploy may be condemnable, but their identities are not all one dimensional. Dickie’s affluence doesn’t seem to corrupt his generosity, and Marge is not excused from feeling contempt for Tom’s closeness to her boyfriend.

In spite of Ripley’s killing and scheming, his anguish, loneliness and desolate financial situation evoke sympathy for a relatable phase in life — lack of identity. “Ripley” prompts viewers to rethink the traditional notion of an anti-hero.

Contact Kaitlyn Sze Tu at [email protected].