The Korean peninsula has had a dynamic history of violence, turmoil and power division — with a constant influx of foreign influences, the region fueled artistic ingenuity. With works dating from prehistoric to contemporary times, “Lineages: Korean Art at The Met” highlights the efforts of Korean artists to adapt to these changes.

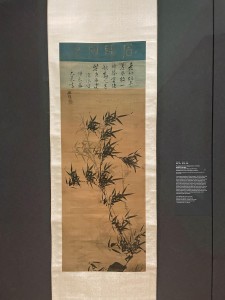

The artists draw traditional techniques and inspiration from visual art forms, like calligraphy. The layered bamboo canvas painting from the early 17th century, “Bamboo in the wind” by Yi Jeong, who goes by the artist name Tanuen, serves as a representation of tranquility, with its dual tones of light and dark colors. The work represents the Chinese philosophical ideas of Daoism and Confucianism.

The philosophies are also represented in the calligraphy, translated by Tim Zhang, which reads, “Aged bamboo has grown unevenly / Branches lift together in the breeze / Desolate and sparse, seeking to stir people / Lingering response found nowhere else.”

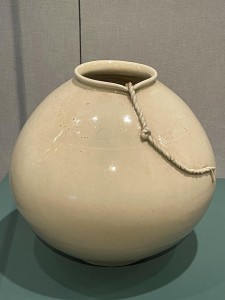

Lee Seung-taek’s “Tied White Porcelain” — depicting a ceramic jar with a rope coming out of it — features similar values, even though the pieces of art are separated by centuries. “Tied White Porcelain” is an example of Korean pottery called a moon jar. Moon jars — spherical, white-porcelain jars made by joining together the two hemispheres — have become globally recognizable thanks to the 2018 Winter Olympic Games held in PyeongChang, South Korea, as the ceremonial lighting of the cauldron was inspired by the distinctive white porcelain.

Since the 20th century, moon jars have been seen as distinguished pieces of art that persevered despite authoritarian circumstances. The autocratic regimes of the ’60s and ’70s placed a surcharge on items that aligned with the nationalist agenda, regardless of practicality. Lee’s “Tied White Porcelain” destabilizes this narrative with ingenuity. The rope, fused to what lies inside, is a catalyst unaffected by the stringent laws. The piece maintains a strong sense of identity, despite strangling parameters.

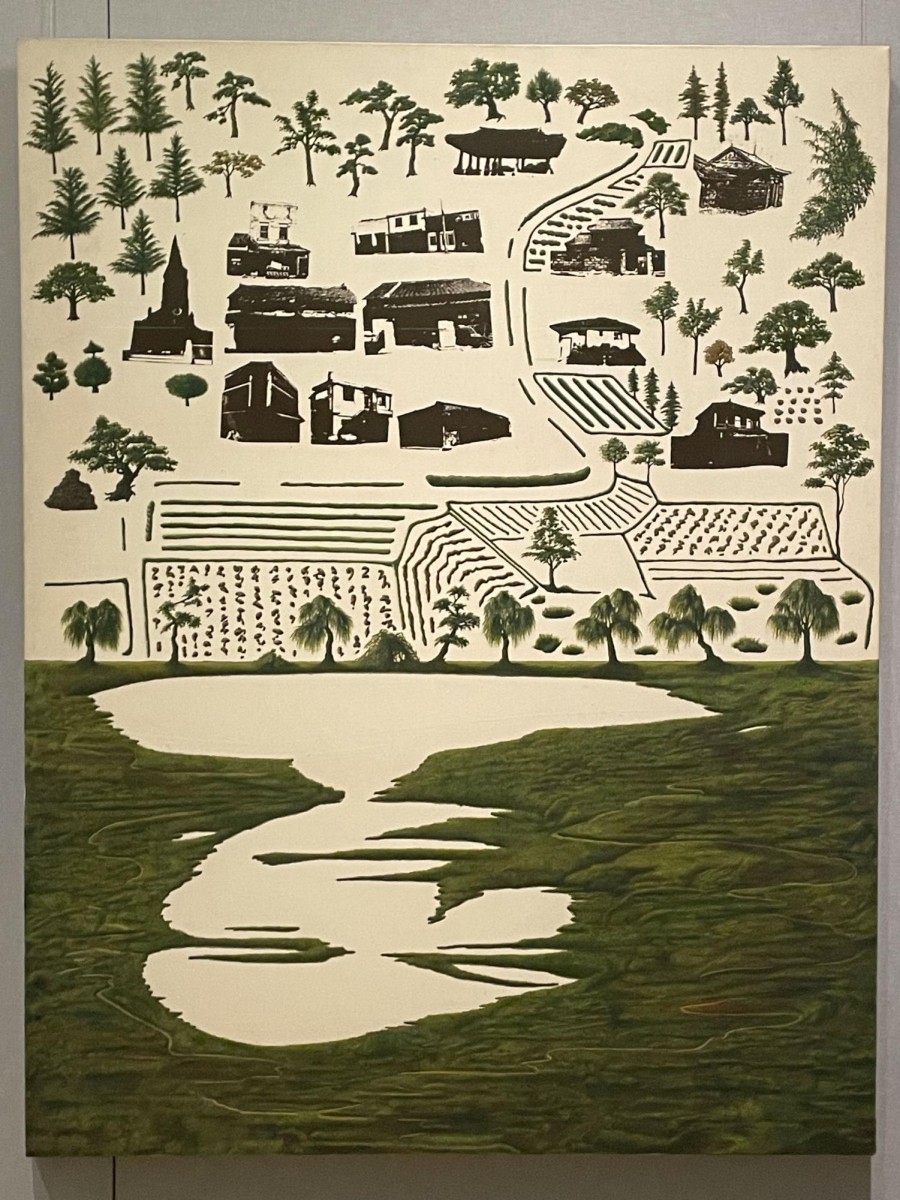

Kim Hong-Joo’s untitled 1993 oil painting visualizes time and setting with its halved composition, representing the demilitarized zone — which resulted from Korea’s division into two separate states. The top section of the painting features a civilization in the process of change, with farms and road-like pathways throughout, conveying a sense of space.

In the lower portion, the composition compresses, creating a trapped feeling. The plush green fields spiral with a speckled body of water in the center, which is an abstracted portrait of Kim. Contrasted with the top portion, the bottom is reminiscent of a blissful walk away from civilization. There are trees along the bottom of the separation line, blocking the luscious view to anyone but the spectator.

This abstract depiction of society produces objective differences. The time surrounding this piece is categorized by political strife, division and uncertainty. Knowing this, Joo’s oil painting still does not favor realist or conservative views, as he does not conform to social and political precedences — he instead paints his own perspective.

Both Lee and Kim’s works represent the pride, resilience, love and pain of contemporary Korean artists. These artists push boundaries, while recognizing what’s at risk if they step over the line.

Korean artists have undergone incredible challenges like autocratic governments, military service, financial insecurity and a lack of recognition. From authoritarian regimes to newfound democracies, uncertainty is inevitable. It can be incredibly unpredictable and dangerous for artists who are unwavering in their beliefs.

Maintaining core values while also setting new precedents for Korean society is an overarching theme of the exhibition. Each work embodies Korean merits while alluding to the events and emotions from the country’s complex history that inspire the works.

Contact Constantine Moore at [email protected].