Whitney exhibition shows why Puerto Rico is not an American paradise

Ending on April 23, “no existe un mundo poshuracán” highlights the talent of more than 15 Puerto Rican artists.

(Natalia Palacino Camargo for WSN)

April 4, 2023

In the United States, we often forget to consider how our national history has not only been shaped by colonialism, but how it has shaped modern colonial projects. Modern colonialism is especially relevant to the history of Puerto Rico’s struggle for autonomy — the island has passed from colonial Spanish rule to annexation by the United States.

In a 1901 Supreme Court decision, Puerto Rico was declared an “unincorporated territory,” which effectively rendered it a colony. The island has been under U.S. sovereignty ever since. Its inhabitants have no voting rights outside of local elections — Puerto Ricans cannot vote for president, and do not have a voting representative in Congress.

The difficulties that Puerto Ricans faced after Hurricane Maria were only exacerbated by the ongoing effects of imperialism. Problems that had been percolating before the catastrophe made it much more difficult for the island to recover from the Category 4 hurricane, which struck in 2017.

This exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, “no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria,” presents a view from inside the island as it deals with these issues. The title highlights the impact of the hurricane, nodding to the feeling that, for Puerto Rico, a world could never exist as it did before — in part due to the government’s failure to rebuild the island after the devastating event.

The project is divided into five sections: “Fractured Infrastructures,” “Critiques of Tourism,” “Processing, Grieving, and Reflecting,” “Resistance and Protest” and “Ecology and Landscape.” Altogether, they offer uncensored perspectives and provide a platform for Puerto Rican artists to respond to the island’s imperial history and the events that followed Maria with their artwork. “no existe un mundo poshuracán” is the first exclusively Puerto Rican exhibition at a major U.S. museum, featuring more than 50 artworks from over 15 intergenerational artists.

This thoughtfully curated exhibition voices the concerns of Puerto Ricans, and emphasizes the failure of various entities to serve the island since it came under U.S. rule. Featuring a range of media, including painting, installation art, video, photography, poetry and performance, the exhibition highlights feelings of despair, abandonment, and community. Hopelessness over $90 billion of damage and the failure to improve infrastructure led to a sense of solidarity amongst islanders, forcing them to turn to their own communities for mutual aid.

Works within the exhibition’s “Ecology and Landscape” section focus on the transformation of the landscape and the destruction of its abundant vegetation. In her textile work “Ir y venir (Come and Go),” artist María Lucía Varona delicately embroidered the sunny landscape of the island and displayed the islanders’ history of emigration, often in search of better opportunities elsewhere. While the textile depicts eyes gazing at airplanes flying to and from the island, what stands out from this work is the inscription in its margins. “El pueblo salva el pueblo” translates to “The people save the people,” an expression of community in response to the neglect Puerto Ricans have experienced.

The irony of this neglect is explored in the “Critiques of Tourism” section, with pieces like Sofía Gallisá Muriente’s video, titled “B-Roll.” The video shows promotions geared toward tourists that say, “The government is bending over backward to help,” referring not to islanders but to U.S. investors, as the island continues to be gentrified. In 2021, Bloomberg named Puerto Rico a “paradise” for crypto inventors due to its zero-tax policy on short-term capital gains.

These laws were part of former Gov. Ricardo Rosselló’s attempt to attract foreign interest, and while they painted the island as a blank slate ready for investment after the hurricane, the level of damage is a direct result of decades of neglect and exploitation of its people.

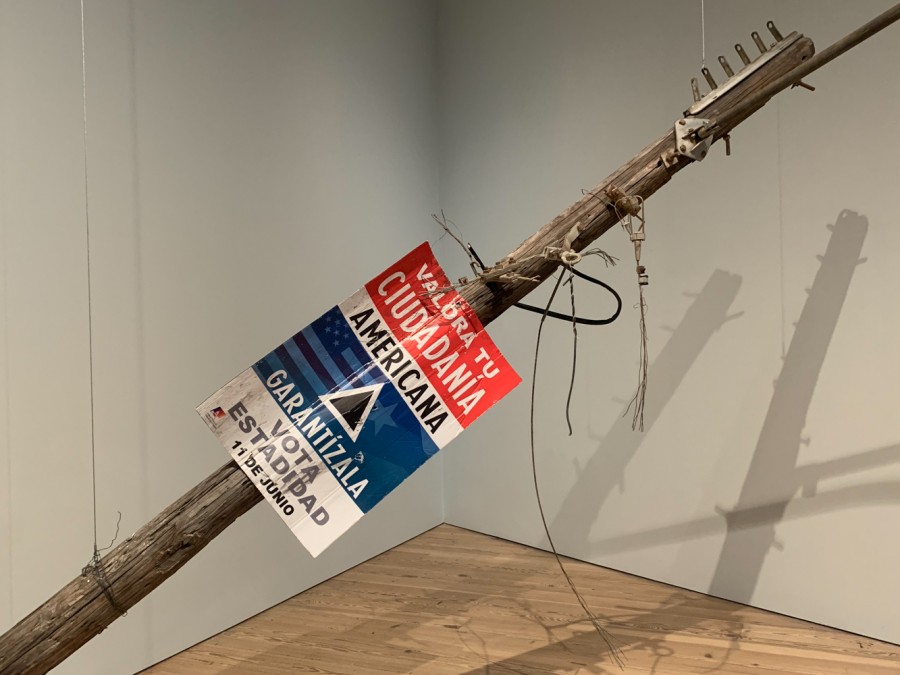

In “Fractured Infrastructures,” artist Gabriella Torres-Ferrer presents “Untitled (Valora tu mentira americana),” which draws a direct connection between the ramifications of the hurricane and Puerto Rico’s status as U.S. territory.

Torres-Ferrer’s piece shows a photograph of a broken lamp post with affixed propaganda telling Puerto Ricans to “value their American citizenship.” The lamp post itself is also installed in the space. In the piece, Torres-Ferrer refers to a nonbinding referendum that took place before the hurricane, in which 97% voted for statehood over independence with a meager 23% turnout. The work reflects on the hopelessness of Puerto Ricans in effecting government change — they are left helpless by overbearing debt and the 2016 enactment of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act — which, ironically, translates to “promise,” and has caused funds to go to repaying debt instead of funding the island’s recovery.

The paintings of Rogelio Báez Vega also capture the nature of this failed promise — he paints abandoned infrastructure, such as a school in “Escuela Tomás Carrión Maduro, Santurce, Puerto Rico — New on the Market” and “Paraíso Móvil,” commenting on the contrast between governmental inaction and the paradise-like lifestyle of some.

The exhibition turns an eye to the experience of islanders that have often been neglected, and the artists present powerful work, empowering through unity instead of victimizing Puerto Ricans. The struggle lived on the island is not simply a matter of natural tragedy, but, as the work shows, it is evidence of an ongoing problem of inequality in which very few are benefiting from the capitalist system in place, and vast numbers of communities are enduring the greater effects of environmental destruction.

Gamaliel Rodríguez’s painting, “Collapsed Soul,” reflects on Puerto Rico’s reliance on the United States for the shipping of basic goods. Showing the sinking of El Faro, a container ship that capsized during Hurricane Joaquin in 2015, the piece is a symbol of the frustration of the island’s dependence due to a 1920s law named the Jones Act, which requires all cargo delivered between U.S ports to be done by ships with American crews. The work is also a reference to the history of how the United States came to acquire the island, as the country won the Spanish-American War after sinking two Spanish squadrons and, consequently, Spain surrendered its Caribbean colonies. Despite their forced patronage, former U.S. president Donald Trump, assisted the most affected victims by throwing rolls of toilet paper at them, painting a picture of the United States’ lack of care.

In “no existe un mundo poshuracán,” the viewer is presented with a sprawling narrative of the difficulty of being Puerto Rican today. The exhibition does not only reflect the effects of Hurricane Maria, but all the underlying problems it brought to light.

Contact Natalia Palacino at [email protected].