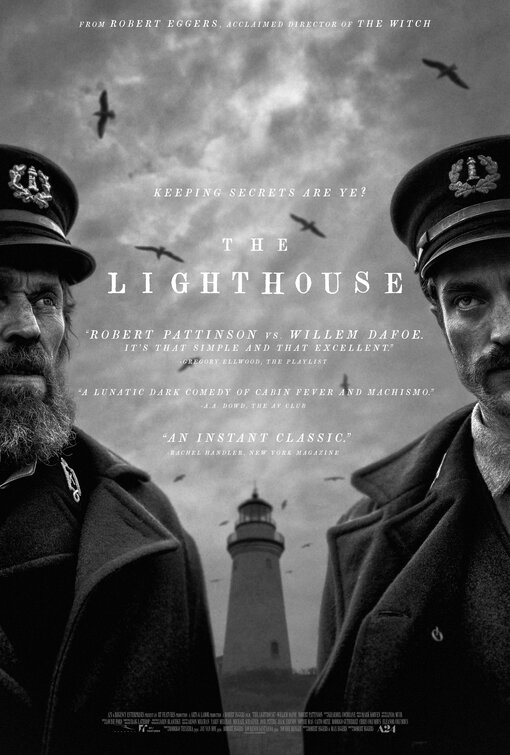

“The Lighthouse” could have been nothing more than a novelty. The stylish black and white veneer of the film that harkens back to early cinema ensured a unique visual treat at the very least, but if it didn’t have meaningful substance to match, it risked being little more than an aesthetically enticing yet shallow piece. Thankfully, Robert Eggers’s second directorial outing runs as deep as the ocean blue itself, offering a deliriously thrilling piece of psychological horror.

Somewhere, out on an island in the Atlantic Sea of the late 1800s, live two unhappy lighthouse keepers. With nowhere to go, no one to talk to besides each other and nothing to do but work and get drunk, the unlikely duo have little but the other’s begrudging companionship. With this basic plot frame, “The Lighthouse” defines itself a disturbing study of passive aggression, selfishness and how many put-downs one can tolerate before they snap.

Robert Pattinson’s Ephraim Winslow and Willem Dafoe’s Thomas Wake serve as perfect foils to one another, with Winslow as the meek, quietly resentful working man and Wake as the irritating, superstitious (and surprisingly gassy) veteran. The main source of the levity in the narrative comes from the two spending the entirety of the film attempting to figure each other out and their constantly changing dynamic, flipping from enemies to friends to enemies once again. At its core, “The Lighthouse” centers around this power struggle. From their first few interactions, it’s already clear that these two characters are barreling down a course bound for collision and the tension never lets up.

It doesn’t take long into the narrative for things to get trippy either, as Winslow’s sanity quickly starts to wane. The movie’s frequent hallucinatory, dreamlike scenes are thoroughly chilling and add a pronounced sense of dread. These sequences introduce several fantastical elements that would ordinarily require a little more justification for existing in a non-supernatural world, but their abstract nature offers a sort of out, allowing the film not to frame them as definitive truths. Much of the story is told from the perspective of Winslow, who, with his increasing dependence on alcohol and his own secrets to hide, hardly constitutes a reliable narrator. This ambiguity grants a delightful amount of room for the viewer to speculate about which events did and didn’t happen, allowing them to make up their own mind about the significance of each scene.

But perhaps the biggest treat of the movie is how lovingly it crafts its murky atmosphere. The set design feels wonderfully aged, evoking the weather-beaten, sand-bleached fixtures of old, rickety beach houses. You can practically smell the salty sea air as it smothers the claustrophobic island and living quarters of the two main characters. The sound design of creaky, dilapidated floors, waves lapping on craggy island shores and ever-watchful seabirds screeching in the distance set the mood flawlessly. “The Lighthouse” drips with coastal horror stylings and effortlessly recreates the mysterious atmosphere of classic nautical folklore and ghost stories.

The technical design of the movie must not be understated either. Returning to monochromatic visuals, mono-audio design and an aspect ratio that’s nearly square all make the movie feel genuinely analogue, as though it were a classic film lost to time that has finally been rediscovered for all to see. Its soundtrack, which also somewhat harkens back to classic horror and suspense films, is downright spine-tingling and complements the eerie backdrop of the film well.

So are there any problems with “The Lighthouse” at all? Well, you might not understand it. Not in the snobby, abstract cinema way either. You literally might not understand it. Both characters, Wake especially, speak in Northeastern American sailor jargon true to the time period, paired with classic nautical accents. It sounds great and helps set the briney tone of the film, but it can often be hard to discern the actual dialogue of the characters. Even when you can make out their words, their frequent use of bizarre expressions may leave you feeling even more lost. This is used for comedic effect — Dafoe’s character often erupts into nonsensical soliloquies that last for minutes on end — but that doesn’t change the fact that it muddles the narrative at times. You probably won’t know exactly what’s happening at certain moments of the plot, which helps add to the movie’s disorienting nature, but also gets frustrating at points where you just want to know what the hell is going on.

Any minor nitpicks are easily forgiven though, because “The Lighthouse” offers one of the most unique cinematic experiences coming out of the industry today. It’s bold, it’s experimental and, above all, it’s downright weird. Employing classic cinematic design on top of the film being a period piece almost lends it a sense of fragility. It’s a new movie, but it also comes pre-aged, and it takes so many risks that any substantial missteps might have broken it apart altogether. Fortunately, “The Lighthouse” feels antique in all the right ways.

A version of this article appears in the Monday, Oct. 21, 2019, print edition. Email Ethan Zack at [email protected].