The history and perception of Chinese food in the United States is long, complex and deeply rooted in racism. Narratives of “Chinese restaurant syndrome,” a term coined in the 1960s based on a fear of MSG, have followed Chinese cuisine for decades, along with the idea that Chinese food is dirty.

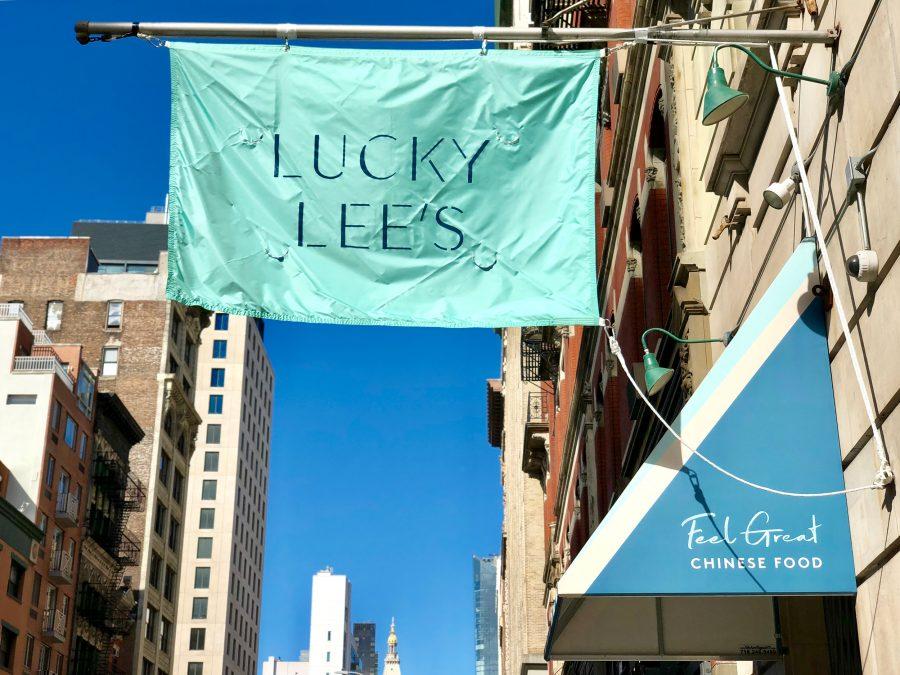

Such narratives perpetuate negative stereotypes that Chinese American communities have been fighting against. Though they started decades ago, these narratives still linger around, as seen in the controversy surrounding recently opened Union Square restaurant Lucky Lee’s, marketed as a healthy and “clean” alternative to American-Chinese food.

Jennifer Berg, associate clinical professor of Nutrition and Food Studies at NYU, dates these narratives around Chinese food all the way back to Chinese immigration into New York as a result of the working conditions on the West Coast at the time. Berg says that Chinese immigrants — leaving the high-fatality railroad jobs behind in California — moved east to New York, where they were relegated to Lower East Side laundromats and restaurants.

“Because the food was so different than what people were eating and because the general living conditions on the Lower East Side were so overcrowded with inadequate plumbing and hygiene, it started these early stereotypical [questions],” she said. “‘Chinese food is suspect, what’s in it? Is there dog in it? What types of animals go into it?’ The palette of what New York was eating was very homogenous and this was something completely different.”

This isn’t to undercut the role that racism played in these negative stereotypes.

“Society always tries to push down people at the bottom, and so recent Chinese migrants were lower on the totem pole than recent immigrants who were also low, but were white.” Berg said. “Race played a huge role in this. Race and racism.”

Decades later, the food landscape in America has changed drastically. Yet Chinese restaurants seem to be fighting an outgrowth of the battles they’ve been fighting for years: cultural appropriation. For the third time in less than a year, a non-Chinese-owned Chinese restaurant is under fire for cultural appropriation.

Following Andrew Zimmern’s controversial statements on his new restaurant Lucky Cricket last year and Gordon Ramsey’s London-based “authentic” Chinese restaurant Lucky Cat — that has no Chinese chefs — openings earlier this year, Lucky Lee’s, which opened on April 8, has come under criticism for cultural appropriation and racist language in its marketing campaign.

A since-deleted post from the restaurant’s Instagram account described the feeling after eating lo mein as “icky” and “bloated,” and offered an alternative in its “HIGH lo mein. Not too oily. Or salty.”

In an interview with WSN, restaurant owner Arielle Haspel said that she was naive in the marketing of her restaurant. “I never meant for the word ‘clean’ to mean anything other than in the ‘clean-eating’ philosophy, which caters towards a specific nutrition and wellness lifestyle,” she said.

Berg says that when looking at the incident in a vacuum, the language can come off as incredibly racist but thinks that “it comes down to whether that was their intention or whether it was just a lack of awareness,” she said. “It seems to have not even crossed their minds.”

For Berg, the intended meaning behind “clean food” was more toward the idea of lighter foods, but the connotation, given the historical context, gives it a different meaning entirely.

“You know language played a big role here as well,” she said. “The word ‘clean’ when you’re talking about an immigrant, is symbolically laden, and I’m sure she totally regrets saying that.”

A nutritionist and health coach by trade, the first-time restaurateur turned to the restaurant’s Instagram page to apologize. A post from April 15, written by Haspel, reads “I am genuinely sorry to have disappointed and hurt so many of you. We learned that our marketing perpetuated negative stereotypes that the Chinese American community has been trying to fight for decades.”

Haspel says that her intention with Lucky Lee’s was “to make people feel great when they walked in and even better when they walk out. My intention is to serve great food, great hospitality, and a great experience.”

While Berg said the apology is a good step forward and might ease the pain that people feel, “the reality was it was a decision that was made that wasn’t thought through.” She suggested that Haspel reach out to the Chinese American community, something that Haspel says she is doing.

“We started engaging the Chinese American community to understand how to make positive changes, and we started to make positive changes,” Haspel said. “Food is always something that unites people and we’re excited to move forward in that way.”

Despite the controversy, diners at Lucky Lee’s seemed unaware or unaffected by the backlash.

Chris, who only gave his first name, said he’s a repeat customer, ordering the kung pao shrimp on this particular visit. Chris said he was vaguely aware of controversy surrounding the restaurant, but he thinks that everyone was over-sensitive and overreacting.

“I don’t know what the intention of the owner was, but what I do know is there’s a general trend towards healthy eating for all cuisines,” he said. “I’m Korean. There’s a trend for that in Korean food. There’s a trend for that in American food and everything so I don’t see why there’s anything wrong with that for Chinese food.”

He also says he doesn’t conflate Lucky Lee’s with authentic Chinese food. “I grew up eating Americanized Chinese food like Panda Express,” he said. “I know they’re not great and I know they’re not great for you, but I grew up having that taste and so I like it. If there’s a healthy way of eating it, I’ll do it.”

However, other people aren’t sold on Lucky Lee’s. CAS sophomore Daryl Tan doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with the concept of “clean eating.” Instead, he has a problem with the name.

“What I don’t like is Lucky Lee’s as the name,” he said. “I know it’s named after her husband, but I feel like it’s a bit disingenuous.”

Berg agrees, saying that while Haspel’s husband’s name is Lee, it is also a Chinese last name.

“It was an appropriation of the name itself,” Berg said.

The appropriation of “Lee” and the other controversial statements such as “HIGH lo mein,” to Berg, might not have struck a nerve on their own, but the combination of multiple issues “comes out as icky.”

The professor offered some advice in the form of a tagline suggestion: “Lucky Lee’s: A Love Affair With Chinese Food Culture.” Berg believes that the owners’ love of Chinese food is genuine.

“At the heart of it, that’s why they opened it,” she said. “It was the cuisine that they love.”

This is a point of contention for Haspel as the cuisine she serves at Lucky Lee’s was inspired by her husband.

“We were proud that Lee’s name was on it because he inspired the idea to open up the restaurant,” she said.

Yet as an entrepreneur, Haspel acknowledged how far the company still has to go.

“We’re still learning,” Haspel said. “We’re still listening. I hope that we can move forward positively so we can eat well, live well and be well together.”

For Berg, this controversy can be a teachable moment.

“It doesn’t have to end with an entire population feeling really slighted and a business folding,” Berg said. “It can end with groups of people growing.”

Email Paul Kim at [email protected]