Steve Locke isn’t just angry. The artist’s work, spanning painting, sculpture, prints and other media, foregrounds the connections between anger, power, shame, desire and love. He is also unapologetic in emphasizing his own human complexities as a queer black man in a time and place where they are constantly denied.

“Steve Locke: in the name of love,” a survey of works by the 56-year-old Boston-based artist, is currently showing in the Gallatin Galleries on the first floor of the Gallatin building.

After seeing one of Locke’s shows last year at Lower East Side gallery yours mine & ours, Keith Miller, the curator of the Gallatin Galleries, invited Locke to show his work in the space.

Locke, a professor at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, also came to NYU in mid-February for a reception, speaking about the show and his artistic practice in conversation with Miller.

Locke’s work is bracingly frank in its examination of queer sex and desire. The piece called “rapture” partially comprises 12 lithographs of men engaged in sex with invisible, partially clothed men — as if they had been carried away by a sort of Biblical rapture, leaving their clothes behind.

“when you’re a boy…” is a wall of pencil sketches, watercolors, polaroids and other images, almost all depicting men and their bodies, clothed and unclothed. Some of the men were lovers of Locke’s who died during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. The piece reaches from floor to ceiling, filling the viewer’s field of vision with an archive of longing and queer desires.

“It was really important it felt like it went on forever,” Locke said.

While Locke’s mere existence as a black queer person is already politicized in a country still reckoning with racism and homophobia, he isn’t afraid to lean into the overtly political. He still emphasizes his inescapable personal connection to these structures of oppression.

“rapture” also includes a tapestry printed twice with a photograph of Locke as a child. In each image, the boy’s eyes are obscured by a black bar, printed with white text — “God is love,” reads the first; “you little f-ggot,” reads the other. The final element of the piece is a video loop of a man preaching about the sinfulness of homosexuality; Locke encountered the footage running when he was a child on Boston public access television.

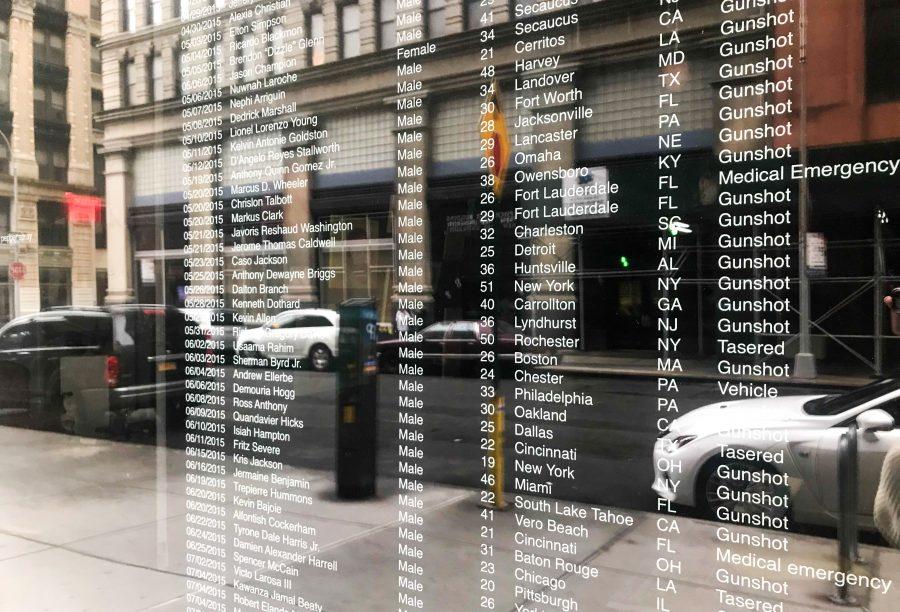

“A Partial List of Unarmed African-Americans who were Killed By Police or Who Died in Police Custody During My Sabbatical from Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014-2015” is a clinical catalog of the names, dates and manners of death of black Americans killed by police. The sheer scale of the list is shocking, but its presentation — as a window decal, facing the street — implicates not only the gallery-goers but anyone who passes by.

“People don’t have any mercy,” wrote James Baldwin in his novel “Another Country.” “They tear you limb from limb, in the name of love.”

“in the name of love” — it’s an apt choice for this empathetic body of work, one that doesn’t shy away from the complexities of suffering, or of love.

“Steve Locke: in the name of love” is showing at the Gallatin Galleries, 1 Washington Place, through March 1.

A version of this article appears in the Monday, Feb. 25, 2019, print edition. Email Alex Cullina at [email protected].