Every semester, thousands of aspiring doctors, engineers, surgeons and researchers square up against a common foe, one they must tackle before their days of hypothesizing and diagnosing can commence: the exam. In preparation for this struggle, they spend many hours being talked at by a professor amid a sea of blank-faced peers. While the majority of undergraduates run into large exam-focused lectures at some point, for STEM and pre-medical students, it’s the backbone of their educational experience. We know that general chemistry isn’t typically taught seminar-style. But can that be reimagined?

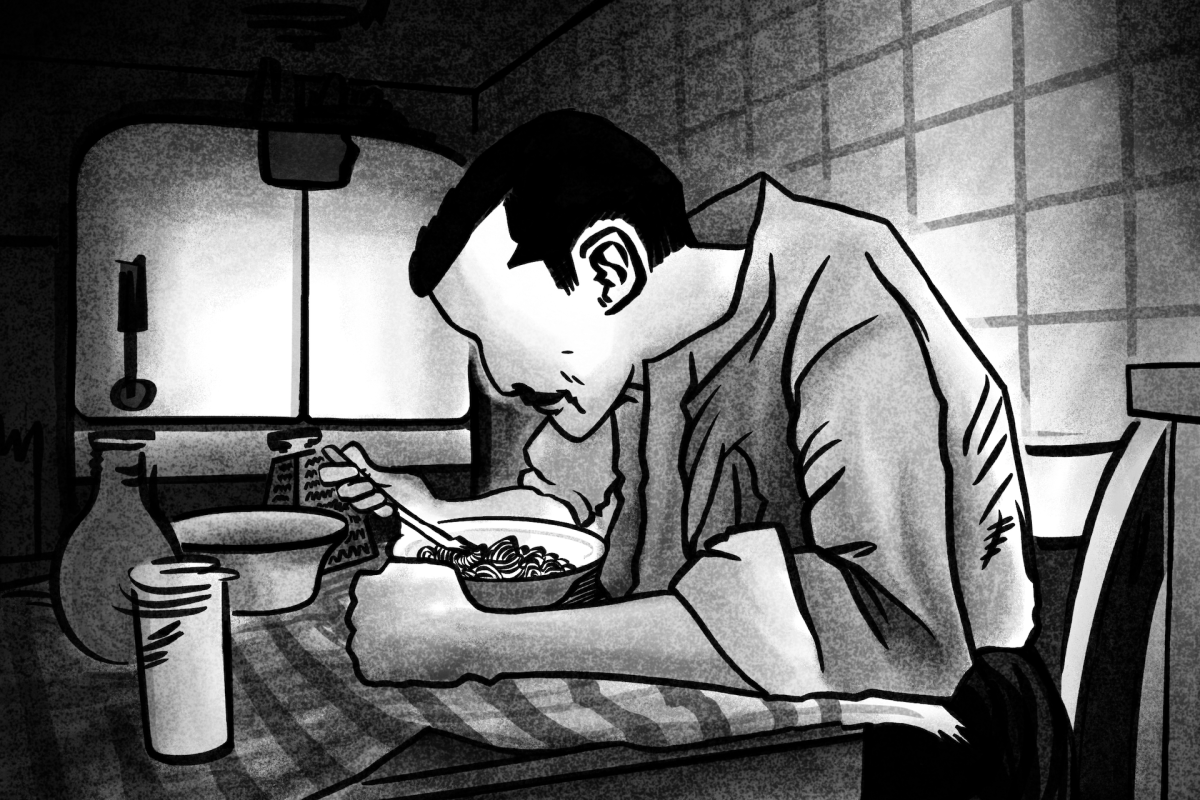

Given the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it scope of most science lectures, most students need to digest material in the most time-efficient way possible in order to stay afloat, rarely getting the chance to pick apart the abstract ideas thrown at them. The textbook-to-exam coursework doesn’t take into account the soft skills that modern medical and research careers demand. There are other means of evaluating students beyond their coursework, but a solid GPA is crucial to being competitive in STEM — not only for medical and graduate school applications, but for the more hands-on research and internship opportunities where original ideas and team players really shine.

While grasping complex material and working well under pressure are crucial, true success and innovation require more than just standard scientific chops; scientists need the abstract thinking skills of philosophers, the persuasiveness of law students and the creativity of artists. Being a scientist means stabbing at problems in a dark box with a long stick; one seldom sees exactly what they’re dealing with, and alleged facts are constantly being rewritten when new discoveries are made. Thinking as quickly as possible in a straight line is counterproductive in the field. And given the constant need for communication and collaboration — whether with fellow researchers, physicians, nurses or patients — as well as the myriad of presentations physicians and researchers must give at talks and conferences, exams alone cannot accurately reflect a scientist’s competence.

Admittedly, not all science classes are taught entirely via lectures. NYU offers several science courses in seminar-style discussion and problem-based learning. Even so, these classes are few and far between, and most still base grades on nothing more than a few quizzes and exams, with lab counting for a small additional portion. Furthermore, the majority of these classes are offered only to juniors and seniors who have already made it past the grind of infamous, lower-level weed-out classes like Principles of Biology and Physics I. Though conceptually challenging, much of the strain of these classes comes from their format. Thus, many creative and passionate aspiring science majors may find their initial courses unfulfilling and drop out for a more interactive degree path, despite their strong ability to grasp the material. By turning students into information-grinding machines, the current system alienates the philosophically-minded future researcher and the group-oriented future doctor, depriving the world of their potential.

Naturally, many practical constraints prevent an ideal undergraduate science education system, the most obvious being the large number of students pursuing STEM subjects and the lack of resources for individualized learning. Furthermore, given the wealth of topics at hand, there doesn’t seem to be time to explore concepts from another angle. The idea is not to completely change the traditional lecture or exam (or to ask students to write philosophical essays on benzene). But small steps can be taken toward a more dynamic approach that will bring life to studying science and produce a more holistic transcript.

NYU could rethink weekly recitation sections — normally spent rehashing lecture material in a smaller setting — as seminar-style supplementary classes. Textbook readings could be supplemented by excerpts from peer-reviewed articles depicting real-life studies relating to class material. Group discussions can invite students to pinpoint potential flaws in the research taught in class, or solutions to questions that are still up in the air. Students can design their own studies in groups or present related studies of their choice. Regardless of the method for change, one thing is certain: being a neurosurgeon depends on more than one’s ability to write open response questions on genetics or fill in a physical chemistry multiple choice quiz.

Opinions expressed on the editorial pages are not necessarily those of WSN, and our publication of opinions is not an endorsement of them.

A version of this article appeared in the Tuesday, Feb. 19, 2019, print edition. Email Vivian Holland at [email protected].