Inside the operating room during a 25-hour face transplant surgery, Dr. Eduardo Rodriguez had time to take just one bathroom break and a quick sip of coffee. The rest of his time consisted of working under the microscope to remove the face of a deceased donor and place it onto Cameron Underwood, who lost the majority of his jaw, lips, nose and chin to a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Rodriguez and his team removed the skin, tissue, fat, muscle, all the nerves that move the face and provide sensation, muscles of facial expression, the jaw, the eye sockets, the teeth, the pallet and all the tissue below the tongue of the donor. This process took about 12 hours, after which Rodriguez began to reconstruct the face onto Underwood until the end of the surgery. He connected all the bones with plates and screws, connected the major blood vessels and every single strand of nerve. Then he tailored the skin around the eyelids, around the nose, around the lips, around the neck and in front of the ears. Lastly, he repaired the pallet and the floor of the mouth.

“25-hours later, Cameron had a new face,” Rodriguez said.

In November 2005, a team of surgeons in France performed the first successful partial face transplant on Isabelle Dinoire, who lost parts of her cheeks, nose, lips and chin after her dog severely bit her earlier that year. Five years later, 30 Spanish doctors carried out the first successful full-face transplant on a man who was injured from a shooting accident. Since 2005, there have been over 40 face transplant surgeries done around the world.

At NYU Langone, the first face transplant took place in 2015 on firefighter Patrick Hardison, who suffered from severe burns while on duty. Underwood’s face transplant is the second transplant done at NYU Langone and Rodriguez’s third in his career.

While NYU Langone receives many requests for face transplants, most cases qualify for reconstructive plastic surgeries rather than face transplants. Candidates that qualify for the latter tend to suffer from severe deformities with missing tissues which inhibit the face from functioning and feeling sensations. Plastic surgeons cannot recreate those facial features from already existing skin tissues.

“For example, [for] lips, we can take tissue from your arms or thighs and we can make or draw some shapes from the tissue, so that it looks like a lip,” Rodriguez said. “But it won’t move [or] have sensations like a normal lip.”

Rodriguez completed his residency at the Johns Hopkins Department of Plastics and Reconstructive Surgery in Baltimore, where the doctor cited a notable beginning to his long journey into plastic surgery. On Sept. 11, 2001, he had just finished an operation as the first hijacked airplane crashed into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.

“In a very short period of time our institution was put on high alert,” Rodriguez said. “We were all trying to get as many of the people that were not critically ill out of the hospital to open up beds for potential casualties.”

After his residency at Johns Hopkins, Rodriguez was asked to assist in the treatment of soldiers coming back from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to complete specialized training. Rodriguez developed a great relationship with the center and received patients from different military and medical hospitals throughout the country.

“Some of them were Navy SEALs, some of them were Delta Force … really high-level operation soldiers,” Rodriguez said. “They were people who basically bleed to protect our freedoms, so it was a great honor to care for them.”

Those coming back from the war had injuries that, despite advanced surgical techniques, still limited their options for recovery. In order to secure funding, Rodriguez transplanted the face of one live monkey onto another. Then, in 2012, Rodriguez performed his first human transplant on Richard Norris at the University of Maryland.

Unlike Rodriguez’s previous patients, Underwood suffered for about 18 months — the other recipients of face transplants lived with their deformities for decades. According to Rodriguez, patients with decades-old deformities experience far more severe emotional suffering than those who get treated relatively quickly.

“In Cameron’s case, the fact that we got to him so soon, we could avoid all that emotional scarring,” Rodriguez said. “He’s going to have some emotional scarring from the injury, but it’s going to be far less than someone who lived with that deformity for years.”

One of the biggest impediments to face transplant surgery is also finding the right donor.

“Finding a donor is difficult,” Rodriguez said. “It’s like trying to find a needle in a haystack,” Rodriguez said. “We have to find someone who matches not only blood type but skin color, skeletal structure, antibody profile — we look at everything very carefully.”

Once NYU Langone found a match for Underwood through organ donor organization LiveonNY, contracting pilots flew him out right before a snowstorm — when all commercial flights to New York City were canceled — to begin the surgery.

Thanks to major technological advances in the field, the team completed the transplant in 25 hours.

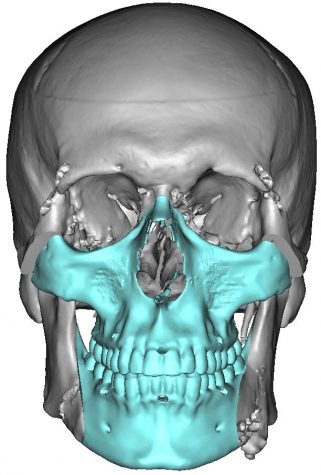

The LaGuardia Studio provided a 3D printing lab to create a mask of the donor, allowing doctors to respect the post-mortem spiritual rights of the patient’s family. Additionally, intraoperative navigation — which works almost like a GPS — helps guide surgeons to precisely place the face on the recipient. Intraoperative CT scanning then helps to confirm the placement of the new face.

The team also meticulously rehearsed on cadavers inside the operating room in order to familiarize themselves with the exact steps of the procedure. By the time they got to the operating room, they had rehearsed numerous times.

“Everyone knows what they need to do,” Rodriguez said. “We’ve rehearsed it enough and now it’s game time. Let’s do what we do best and get this kid out of the operating room. That’s what we do.”

Despite the length of the surgery, Rodriguez and his team didn’t feel fatigue.

“I don’t feel tired at all,” Rodriguez said. “When someone’s life is dependent on you, I don’t have one iota of rest or concern. There’s so much adrenaline flowing in my bloodstream that until we’re out safely, I cannot be at peace.”

The entire process was an immensely emotional one for everyone involved, but the reward of a successful surgery was worth it.

“There’s nothing more rewarding in my life,” Rodriguez said. “That’s why, irrespective of material possessions, I feel that I am rich because I can care for people like this and give them another chance at hope and life.”

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, Dec. 3 print edition.

Email Kristina Hayhurst and Meghna Maharishi at [email protected].