On May 8, 1987, Senator Gary Hart withdrew from the 1988 presidential race. It was the end of his campaign, but only the beginning of an era rooted in sensationalism, celebrity and pop culture.

Hart was a shoe-in for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Everyone expected it, but no one could have predicted the sudden downward spiral his campaign would soon take. A rumor of an extramarital affair with Donna Rice — then a model and actress — was a turning point in his campaign, but more importantly, it changed the face of American politics.

In “All the Truth Is Out,” the book that inspired the upcoming film “The Front Runner,” author and political columnist Matt Bai returns to Hart’s story, but to tell it through a different lens. He reflects on how Hart’s scandal wasn’t just the downfall of one man — it was the downfall of an entire political world at the hands of the media.

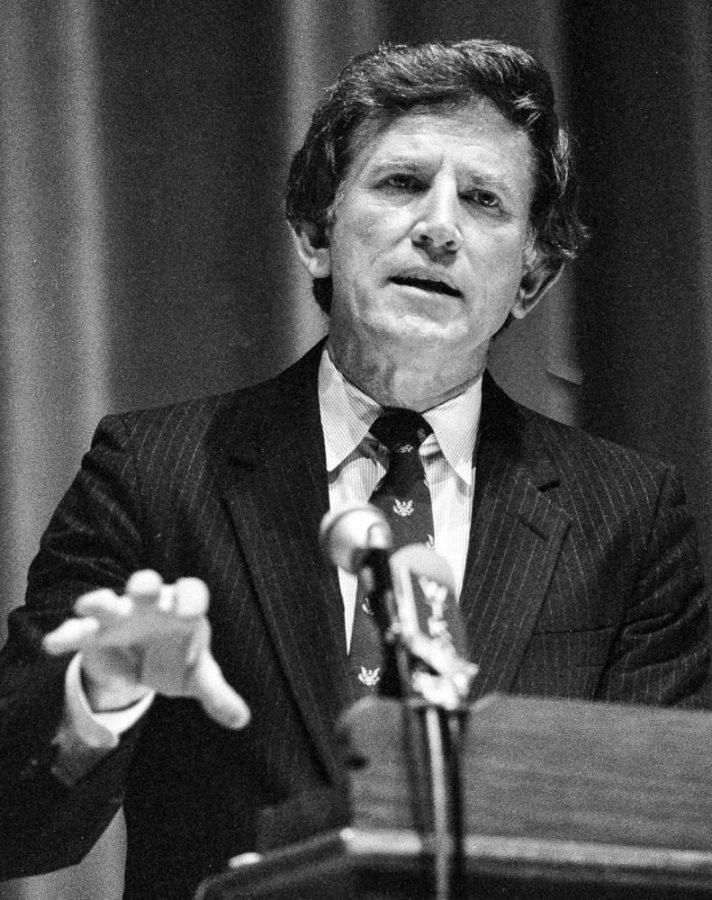

WSN spoke with Bai about his book, Gary Hart’s unique character and how politics have changed since that fateful week in 1987.

Washington Square News: “All the Truth Is Out” was published four years ago, but a lot has changed in that time with the Trump administration and even media itself. How do you think media has evolved and changed politics?

Matt Bai: The political moment that we’re living in since that time is very much consistent with the events and the message in the book. The point to me of the story of 1987 was always that that was a moment where politics and entertainment collided, and ever since we treat politicians more like celebrities. When you create a process that treats candidates like celebrities, you’re inevitably going to draw celebrities into your political process. To me, there’s a direct through line from Hart to Donald Trump. There’s been some really good journalism done on this administration and there’s certainly an awareness that the process isn’t working, but I think there’s still a reluctance among leading journalists and journalism organizations to really reckon with their role — our role — in bringing this moment about. It’s fine, and I think appropriate, to oppose and stand up to President Trump’s bullying of the press and his reckless campaign against the credibility of a free press, but along with that, I think there’s some responsibility to reckon with what we did to help create this moment and to help make him possible.

WSN: Do you even think that it’s possible that we might return to an era of journalism, if such an era even existed, where we can just report on the truth and what’s happening?

MB: Nobody’s going to make me the journalism czar and I don’t really want to be, so I never considered it my role or my ambition to remake the media or tell other journalists how they should behave. To the extent that I was making a point about journalism in the book, it’s the point I make in the end, which is that we all have agency and responsibility and judgment. For the entire time I’ve covered politics, there’s been a feeling that stories are just out there and moving of their own volition and that we’re just twigs in a current and the current carries us where it carries us. If one organization is covering a story, then you have to cover that story. There’s been a sense that we don’t control the flow of news; we just have to go cover it. I think that’s a mistake. I think the one thing I wish we could all agree on is we do have a responsibility to exercise judgment about every story. There is no one rule that says “you cover a personal life if A, but you don’t cover it if B.” Every case is different. The thing that has to govern us is our individual judgment. For too long, I think we’ve abdicated that. We’ve basically said, in every other aspect of news, we are gatekeepers and we make judgments, but when it comes to the personal lives and celebritization of politicians, we just throw up our hands and abdicate because that’s what the voters want and there’s nothing we can do.’ Every individual reporter and individual editor gets to make decisions that enable us to go to sleep at night feeling like we’ve been the journalists that we set out to be. Hopefully, if any young journalist took anything from the book, it was that.

WSN: In terms of Gary Hart, you mentioned the ’80s was the clash between entertainment and politics. What do you think was the cultural aspect of the ’80s that made this happen?

MB: There were a lot of forces churning in the mid-1980s that you can see, in retrospect, made that moment inevitable. If it had not been Hart, it would have been someone else. He sort of walked into it. You were about a decade removed from Watergate and the renewed emphasis that that scandal had put on the character — the moral character — of politicians. You had the rise of the feminism on the left which changed attitudes [toward] adultery. You had the rise of the moral majority on the right, so that suddenly personal behavior mattered a lot more than it used to. Then you had the birth of the satellite TV. You had the flyaway satellite dish and cable TV and punditry which played a huge role because it meant that you could essentially follow a story from anywhere, minute-by-minute, and the goal was to keep viewers in their [seats] and that creates more of an entertainment cult. All of those things were churning on the edge of our politics in the mid-1980s and Hart walked into it. A lot of the underpinning of the book is that it was easier to see 25 or 30 years later than it was at the time.

WSN: Do you think Hart’s character got in the way of his success in the sense that he refused to for one, he refused to corroborate Donna Rice in any of this and he kept coming back to this accusation instead of just one time saying, ‘no, this didn’t happen?’

MB: [Hart] came from a different era of politics. He didn’t believe the public or the press [were] entitled to that information. When you create a process that demands a candidate be willing to subject himself or herself to any level of scrutiny and disclosure and humiliation, you’re going to draw into that process a certain kind of candidate. You’re not going to get Gary Hart. Gary Hart wouldn’t have run 20 years later because you’re not going to get someone who values privacy and dignity and a certain remove from public life more than holding the office itself. You’re going to get people who will do anything to win and say anything to win. The process by which you select your leaders has a tremendous amount to do with how they end up governing. The real point of it is, is not what Hart was or was not willing to do, the point is who is willing to do that and what that means for our politics ever after.

WSN: I want to go into the film a little bit. When you were writing the film, how was that process like — did you find it more difficult than when you were writing the book?

MB: It was more difficult only because I didn’t know anything about screenwriting when I started out. It was less difficult in the sense that I had tremendous partners. I had this great collaboration with Jay Carson, who I started out writing with, and Jason Reitman, our director, who is just a brilliant writer and director. It’s not an especially hard story to tell on screen because it has these six or eight or 10 vivid scenes that are both real and incredibly cinematic. The challenge for all of us is that we set out to tell a really complicated story around a bunch of different characters. We didn’t want you to just sit on Hart’s shoulders the entire movie, we wanted you to see the dilemmas that everybody faced: the candidate and the aides and the journalists. We wanted to give each of them their argument. We didn’t want to make anyone a villain or a hero. And we wanted it to feel real. We wanted you to feel like you were dropped into the world of political campaigns in 1987. That was challenging. It’s an unusual and chaotic movie with a lot of characters and a lot of dialogue happening at once. It’s a movie that, as Jason [Reitman] says, is constantly asking people in the audience what they should be paying attention to and what they should be listening to.

WSN: What do you hope the audience takes away from the film?

MB: We all hope that they take away different things. That’s the goal of this movie, not to leave you with a message. [We want to] to leave you a little bit perplexed and to have people walking out of the theater, arguing about it or talking about it. We’re really asking people to reflect on the decisions that everybody made at that moment and where we are today and how those things relate. We’ve been overjoyed to this point to see in the screenings and festivals people really having a conversation about it as soon as the lights come up and different people taking away different lessons and siding with different characters.

WSN: Do you think that with how the media is now and the current political administration people will find it relevant and if that might affect how they view it in retrospect?

MB: I hope they find it relevant because it is relevant. When Hart gives that withdrawal speech at the end, he says ‘I tremble for my country when I think we may, in fact, get the kind of leaders we deserve.’ I think that really hits people and is, in some ways, the whole point that you want people to be debating. They may take away different lessons for how its relevant but it’s clearly more than just a period piece. At the same time, we don’t make that connection for people. We don’t bang you over the head with it. We’re telling a discrete story of a moment and it’s not a message story, it’s a pretty gripping, cinematic story that stands on its own

WSN: Hart said, “A man’s judgment had to be measured over 15 years in public life, not by a single weekend.” Do you think that extends to presidents and public leaders? Is it possible to judge politicians with this moral spectrum?

MB: I hope so. You’ve seized on a part of the book that’s really important to me. It’s a theme that I come back to in a lot of my work, which is the idea that people are more than a moment and they’re more than their worst moment. Sometimes, a person can do something so egregious, I suppose, that it does define their character and who they are. I think that’s at the center of the book: it’s asking can we judge character and judgment and fitness in the context of a life and in the context of a career, rather than discarding people and making heroes of them one day and then berating them the next? I think that is, in some ways, the test of a sophisticated and constructive media. I would go so far as to say that it has to be a hallmark of a media that helps its country vet candidates, which is the ability to see people for the whole of their careers and lives just as we would want people to see us. I certainly hope we get better at that.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, Oct. 29 print edition. Email Daniella Nichinson at [email protected].