Returning Puerto Rican Students Face Uncertainty

April 29, 2018

From left to right: Alex, Mariana, Sophia and Jamaris sing “Salimos de Aquí” by Fiel a la Vega while hanging out.

Dispersed around Sophia and Alex’s room one night, Jamaris and her three friends belt out the lyrics to “Salimos de Aquí” by Fiel a la Vega. Mariana leads the group, dancing around the room taking each of the girls’ hands. The song comes to a close and Jamaris hits pause, turning to her friends.

“Have you guys heard this song?” Jamaris asks, as she hits play on “Mi Duena” by Kany Garcia.

It’s a unanimous ‘no.’

She gasps, runs to the light switch and the room goes dark — only illuminated by the city lights outside. A guitar greets Garcia’s words, and the girls’ energy dims as they melt to the floor. The somber lyrics flood their ears, and suddenly, there’s only one thing on their minds: home.

It has been almost five months since Jamaris Martinez-Lugo, her three friends and 53 other students left Puerto Rico for the United States. Much of the island was ravished by the Category 5 Hurricane Maria after it struck on Sept. 20. Puerto Rico was left in ruins, with its government estimating that 200,000 residents will leave the U.S. territory by the end of 2018, causing the population to drop by 5 percent, according to The Washington Post.

In November 2017, NYU announced that it would be offering admission to 50 students from Puerto Rico affected by Hurricane Maria under the Hurricane Maria Assistance Program. After an influx of 400 applications, NYU extended its offer to an additional 13 students, bringing the total of accepted students to 63 — 57 of which decided to attend.

NYU’s program covers the visiting students’ tuition, meal plans, healthcare and housing. Three other American universities — Tulane University, Brown University and Cornell University — offered similar programs.

The process of implementing such programs was not well-received by Puerto Rican academia, who shared their concerns by writing a commentary in the Chronicle of a Higher Education. The writers stated programs like HMAP could eventually lead to lower enrollment rates and closed courses in Puerto Rican universities. There’s also the underlying fear that their “excellent students are being lured away by offers that sometimes include tuition waivers, housing and meals.” But students still believe that the island hasn’t made enough progress in rebuilding for them to return.

Now, as their semester at NYU draws to a close, students in the HMAP program are asking NYU to extend the program another semester. The HMAP Students Initiative, which has the support of 27 of the visiting students, penned a letter addressed to President Andrew Hamilton on April 27. In the letter, they cite the upcoming hurricane season and the time Puerto Rico still needs to rebuild.

NYU already has a program within the Academic Achievement Program where students from the University of Puerto Rico and the University of the Sacred Heart in Puerto Rico can study at NYU for a semester, but only a few students are even accepted into the program.

Growing up, many of the HMAP students dreamed of attending NYU. But they never imagined they’d ever get the opportunity.

“I’d always wanted to come to NYU, but it was never a possibility — it was just a mere dream of mine that I never thought would become a reality,” said Martinez-Lugo, a visiting sophomore studying Education at University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras. “The hurricane was a horrible thing, but this came out of it.”

The HMAP students come from a number of different universities, both public and private, with majors ranging from Drama to Electrical Engineering. While many of the students came from the same Puerto Rican universities, most did not know anyone when they arrived in New York.

“I think they [NYU] wanted to make sure that if you came alone, you didn’t leave alone,” Mariana Cabiya, a visiting sophomore from the University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras studying Drama, said.

Through the mixers and events organized by NYU resources such as the Academic Achievement Program and the Center for Multicultural Education and Programs, the visiting students were able to familiarize themselves with people taking part in the program — and even meet people from their home colleges. Planned activities included Yankees games, Broadway shows and group dinners. In addition to these events, students were also matched with mentors through the Hurricane Maria Mentorship Program to help with the transition into NYU.

“I think one of the biggest support systems were the people that I met here,” junior Salomé Ramirez, a visiting student from the University of the Sacred Heart, said. “We share the same story and we are here with the same purpose.”

While the students have enjoyed their time at NYU, their hearts ache for their family and friends back in Puerto Rico, who continue to suffer from the hurricane’s damage.

Mariana Cabiya and her mother wash their clothes.

“I didn’t want to leave my family without electricity,” said Adriana Melendez, a sophomore at University of Turabo studying Communications. “I didn’t like the idea of me living in an apartment with a ton of stuff while my family was without power.”

Mariana Cabiya, a visiting sophomore from the University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras studying Drama, also found it difficult to leave her loved ones behind.

“They’re like, ‘So we have to stay here while you’re in New York City?’” Cabiya said. “That kind of sucks, but it doesn’t suck that [we] get to do something for [our] future. That’s something we shouldn’t be ashamed of, or feel guilty about.”

It is safe to say that being away from home these past months has been hard for all the visiting students. Like many of her peers, Sophia Rodriguez Rosado, a sophomore in the University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras studying Communications, is ready to return home.

“Being here is awesome, but I want to go back,” Rosado said. “I want to be living what they’re living right now. I want to go through the blackouts. I want to go through having no water for a day because those are my people. I want to be there, going through what they’re going through.”

This feeling of powerlessness echoes through the HMAP students, who yearn to be there for their families as they piece their lives and the island back together. Puerto Ricans are still struggling to rebuild, especially those living outside of the metropolitan areas. Many of these small communities have yet to regain running water and electricity.

On April 12, the country suffered from an island-wide power outage, which has been categorized as the second-largest blackout in history, further proving how weak the electrical grid is. Carlos Matos, a sophomore at University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez studying Electrical Engineering, believes even the smallest of future hits could cause catastrophic damage.

“One of the power outages was because of a tree fall,” Matos said. “We cannot predict the future, but it concerns us that this infrastructure was brought to its knees by a tree. A simple storm can therefore affect in massive ways.”

Mariana Cabiya’s father tries to clear out the road covered in trees after the hurricane.

For the past seven months, Puerto Ricans have been living in a constant state of uncertainty, never knowing when the power may go out or if school will be canceled. Uncertainty is the new normal for Puerto Rico. As a result, mental health is at an all-time low. There has been an increase in depression, anxiety issues and post traumatic stress disorder among Puerto Ricans, according to a report done by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

“I have anxiety issues, I am deeply triggered by what happened in Hurricane Maria,” Matos said. “When you have that instability, that uncertainty regarding your resources — access to power, access to water — it becomes all you think about.”

Loud winds are especially triggering for those who experienced the forces of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Alex Guardiola Cuevas, a visiting sophomore from the University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras, experienced flashbacks during one of the Nor’easters earlier this year.

“During class when there was a storm brewing, I was on a high floor of [the Tisch building], and you had a perfect view of the city,” Cuevas said. “You could see the wind with the snow, and I was looking out the window thinking, ‘Oh my god, we’re going to die here.’”

Remnants of a residential kitchen in Toa Baja, Puerto Rico, where hurricane waters flooded up to the second floor of many homes. April 2017.

According to Melendez, the hurricane was a defining moment for all Puerto Ricans. They realized where the government’s priorities were — and it wasn’t with the people.

“The hurricane just made everything more clear,” Melendez said. “Last year was a learning opportunity for us. We know now that the government isn’t capable of taking care of the people in this crisis. We know that they won’t respond quickly; we already know what will happen.”

According to students interviewed by WSN, the government has worked toward rebuilding commercial areas of the island, but has overlooked rural communities. They recalled that electricity returned to Milla de Oro — the Wall Street of Puerto Rico — before other parts of the island, including hospitals.

As the lights slowly started to turn on, Cabiya noticed that only business areas had stable electricity. Cabiya, who worked at one of the largest malls in Puerto Rico, mentioned that she returned to work a mere two months after the hurricane hit.

“When the malls are lit up, but the hospitals aren’t, that’s a huge problem,” Cuevas said.

A house is right in front of Jamaris Martinez-Lugo’s grandparent’s house, the house is supposed to be on top of the blue columns on the right side but there was a flood and the river knocked it down.

For Cuevas and her friends, it seems that the Puerto Rican government values money more than its people. How the government handles its finances has been an issue for Puerto Ricans for years. Right now, the education system is facing major cutbacks, which has resulted in the doubling of University of Puerto Rico’s tuition, a decision that was made on Friday, April 20 by the federal board for the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act.

The PROMESA board consists of seven members, appointed by former President Barack Obama, who oversee the restructuring of Puerto Rico’s debt. NYU Law Senior Fellow Arthur J. Gonzalez has been a member of the board since its implementation in 2016 and said the University of Puerto Rico’s tuition increased due to utility costs — something board members have wanted to privatize in the past.

“Reliability has been an issue with the electrical system for years,” Gonzalez said. “With respect to the University of Puerto Rico, it’s a question as to how much funding can the central government afford to provide to the university. And in making that analysis — and that it can’t continue to proceed the way it was proceeding — it resulted in a tuition recommendation increase.”

The Federal Pell Grant — a type of financial aid for college students — will continue to cover tuition for those who cannot afford it. However, according to Gonzalez, the board hopes that the increase in tuition will not deter students from returning to or applying to the University of Puerto Rico campuses. The doubling of tuition has received backlash from current students enrolled in public universities.

Puerto Rican students are no strangers to conflict with the government’s finances. Last year, public schools were suspended for weeks at a time due to strikes.

According to Gonzalez, the board’s efforts are focused on structural, fiscal reforms to revitalize the economy. His priorities and the priorities of the board have been questioned by students like Matos and Cuevas.

“They hire him to keep companies from bankruptcy,” Cuevas said, in reference to Gonzalez. “The thing is, they’re looking at Puerto Rico as a business. We’re not; we’re a country. We have people that are ill, people who need education, people who need their pension, and overall, we are people. We aren’t a company.”

Jamaris Martinez-Lugo’s family collects rainwater.

The visiting students who attend public universities back in Puerto Rico have expressed concerns about returning to higher tuitions — an added problem to the current instability of the island.

“We are just stuck here in this sense of hopelessness, with this fear of what is to come because it is not in our hands to fix this,” Matos said. “In order to help my people, I need to educate myself, but my education is affected by the current state of my people.”

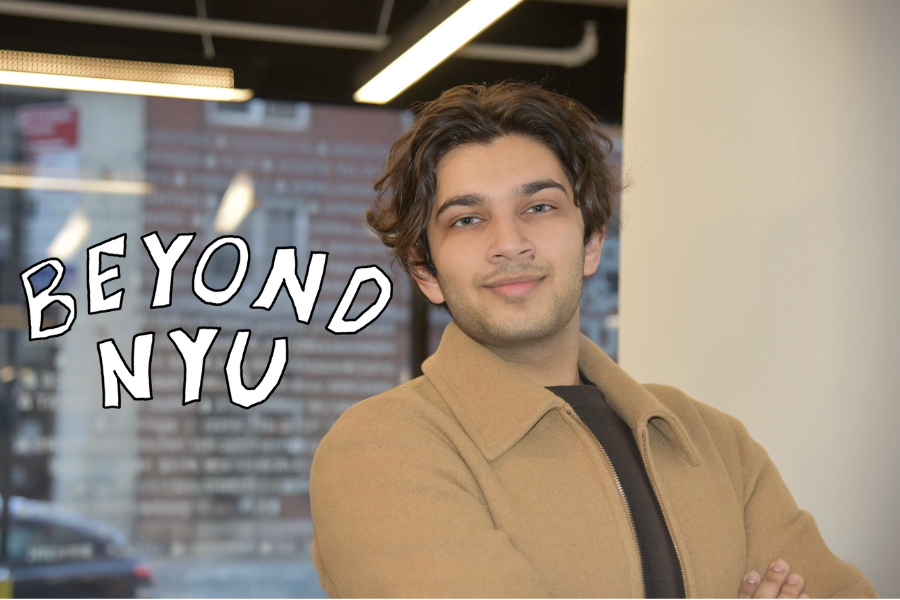

Coming to NYU for a semester has given HMAP students the chance to continue their education during such a tumultuous time. CAS sophomore Rebecca Gelpí, who recently transferred from the Sacred Heart University in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, started at NYU this past semester along with the 57 HMAP students and quickly found a community within them.

“It’s not that I didn’t make friends in my other classes,” Gelpí said. “The other Puerto Rican students came at the same time as me, and we all had such similar experiences. They gave me a community to turn to, and now they all have to return to the island, which is still not fully recovered.”

Many of the students wish to stay longer, as neither the government nor the education system is fully-functioning yet.

As a result, the HMAP Students initiative, which was created by a portion of the visiting students, posted a letter requesting an extension of the Hurricane Maria Assistance Program for one more semester. The initiative posted three versions of the letter on the morning of April 27, each garnering signatures from different groups of people — student groups, faculty and individuals.

After reading drafts of the letter, HMAP students expressed mixed feelings. Many, like Cuevas, showed their support — despite being ready to return home to their families — because at the end of the day, education is their top priority.

“In order for me, and for my family, to have a better tomorrow, I’m going to have to sacrifice a little bit of today,” Cuevas said. “And if NYU gives us the opportunity, I would really like to stay. I know once the opportunity comes, I will have to jump at it, even though I do not want to.”

Ramirez has chosen to be realistic about the situation. Although she would love to stay longer, she thinks it is unlikely that NYU will waive tuition for the same students for an additional semester.

“I just think we have to be realistic and say [we’re] not getting full rides again for the next semester, just because we want to,” Ramirez said.

Melendez feels conflicted about the letter.

“I feel like the university has given us so much already,” Melendez said. “But I do understand that there are students who are not in the condition to actually go back.”

When crafting the letter, members of the initiative emphasized how grateful they are to have received such a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“They are not being forceful or ungrateful,” Ramirez said. “They understand that the university gave them an opportunity, they understand that they are not obligated to do it again. They’re just asking.”

Cabiya shared sentiments similar to Ramirez.

“I thought, ‘How am I supposed to ask these people for more?’” Cabiya said, referring to NYU’s HMAP. “They’ve granted me everything, I don’t want to sound ungrateful in any way.”

As the song came to an end, tears started to trickle down the cheeks of the girls who were filled with the bittersweet feeling of being away. Lying under the string of photos taken back home and the Puerto Rico flag hung on their wall, they prayed for their island to heal.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, April. 30 print edition. Email Natalie Chinn, Yasmin Gulec and Pamela Jew at [email protected].