A Large Step for Womankind in ‘Mercury 13’

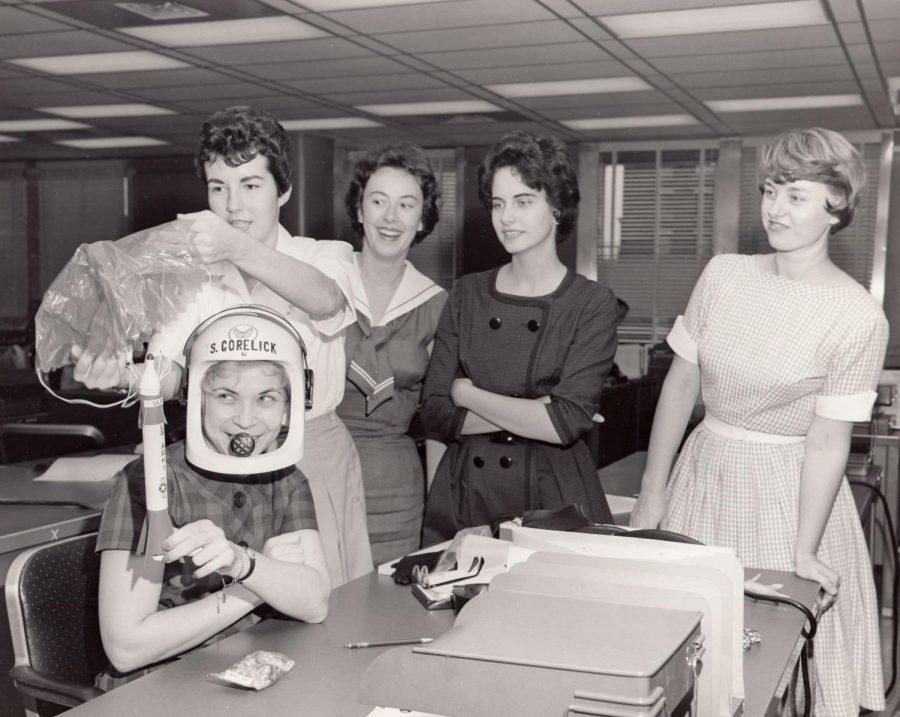

Sarah Ritley and the women of the Mercury era.

April 25, 2018

The Space Race of the 1960s was about innovation and advancement, but at the time, the idea of a female astronaut was still too out of this world for NASA to stomach.

Netflix’s new documentary “Mercury 13” tells the story of 13 female pilots who took part in grueling medical testing in order to become astronauts but were ultimately denied the position because of their gender.

The women all started off as pilots, which in itself was an occupation mostly reserved for men. Sexism pervaded the media coverage these women received throughout their careers. In an archival clip from the documentary, a news commentator’s words on renowned pilot Jacqueline Cochran landing a plane reflect the sexism of the time.

“I wonder how she looks after flying more than 293 miles an hour,” he said. “That’s fast enough to disarrange one’s hair.”

The commonality among these women is that none of them saw themselves as any less capable than their male counterparts. But because of sexist stereotypes, the efforts of these women at home and in the sky were diminished and ignored.

However, they didn’t stop fighting. To them, becoming astronauts and going to the moon seemed like a natural next step in their careers. After being chosen for a test program and undergoing extensive medical tests, the program was canceled. The women took their case to court.

“We ask as citizens of this nation to be allowed to participate with seriousness and sincerity in the making of history now,” one of the women in the courtroom said, “as women have done in the past.”

Sadly, the male-dominated space program feared the rise of women and squandered their efforts. One man even likened sending a woman to space to sending a chimpanzee to space.

“Underneath it all, it’s just some little boy who’s afraid,” one woman said, referring to this man’s comment.

Where the documentary truly excels is in its acknowledgement that, while the Mercury 13 themselves never made it to space, they had an undeniable impact on the role of women in NASA. Many of the 13 and other female astronauts remarked their gratitude for the opportunity, including Eileen Collins, the first woman to pilot the space shuttle.

“If it were not for the Mercury 13, I would not be here today,” Collins said.

A striking juxtaposition of archival footage of rocket launches and women’s rights marches illustrate the parallel histories of feminism and the Space Race. Often considered separately, “Mercury 13” makes the compelling case that these two storylines are more intertwined than they may seem. While NASA worked on sending a man to space, a tide of female empowerment swept across the nation, and a generation of women who would go on to challenge sexist norms rose steadily to the surface.

Overall, “Mercury 13” carries a strong and essential message: fight for what you want and deserve in spite of all obstacles. Even if you don’t reach your ultimate goal, you could inspire future generations to shatter expectations by following in your footsteps.

“Mercury 13” is now available for streaming on Netflix.

Email Taylor Stout at [email protected].