‘Sweet Country’ Takes the Western Down Under

Courtesy of Samuel Goldwyn Films

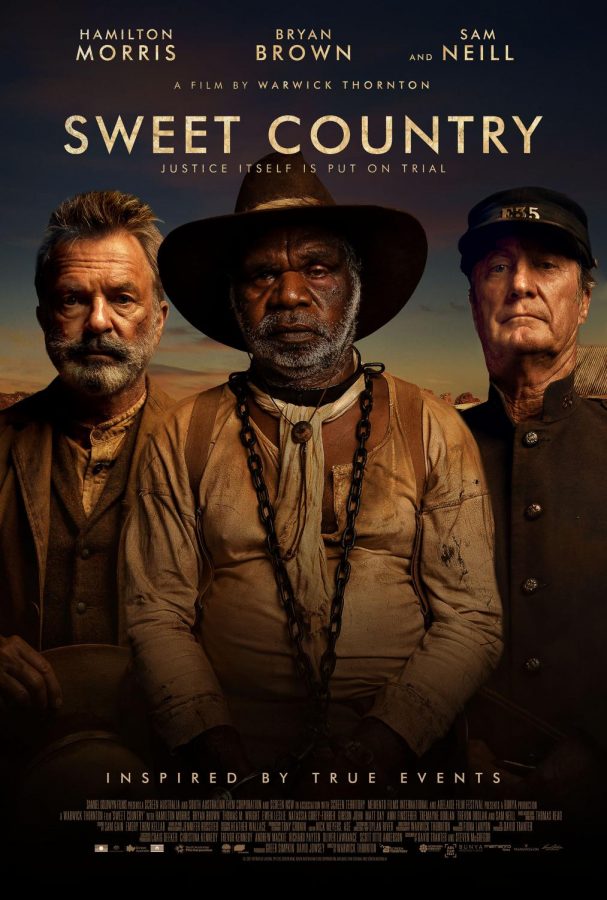

“Sweet Country” pays tribute to the golden age of Western cinema.

April 10, 2018

An unforgiving dry desert landscape, an isolated one-horse town and an outlaw on the run from the local authorities. There is a familiar tone that strikes through Australian director Warwick Thornton’s latest feature film, “Sweet Country,” as its costumes, setting and production design emulate the iconic style of Western cinema.

Set in the late 1920s in rural central Australia, Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris), a middle-aged Aboriginal man, kills an ill-tempered white war veteran in self-defense. Fearing racial injustice at the hands of the local authorities, Sam, accompanied by his wife Lizzie (Natassia Gorey-Furber), set out on foot with little provisions into the harsh Australian outback as a team of local lawmen attempt to hunt them down.

Though the characters are fictional, screenwriter David Tranter loosely based the action of “Sweet Country” around the stories that his grandfather had passed down to him. This personal connection is reflected in the film’s steady and restrained depiction of the events on screen. One such example is Thornton’s creative decision not to include any musical score throughout the film, with the dialogue and natural ambience being the only audible effects. As audiences are accustomed to the emotional guidance that music usually provides, to not include any score to is a risky move. But this decision was utilized by Thornton effectively in order to place all dramatic action back on the characters and force the audience to focus on their adversities, especially those faced by indigenous Australians.

While “Sweet Country” looks at the devastating racial issues that plagued, and still continue to plague, the indigenous people of Australia at the hand of colonizers. However, the film steers away from depicting the characters as being solely good or evil. This moral ambiguity is similar to that of the spaghetti western genre, which presents audiences with heroes and villains whose actions were often racially motivated as part of a well-defined systematic reality. For example, Thornton depicts the character Henry March (Ewen Leslie), the World War I veteran who threatens and abuses the indigenous Australians, to be sympathetic, depicting his suffering from severe Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as a result of his time spent in battle. This detail of March’s character is not used to excuse his actions, but to highlight the fact that these racial prejudices were coming from realistic human characters, rather than fictitious villains.

What is perhaps most unique to “Sweet Country” is its frequent use of flashbacks instead of dialogue to provide exposition. This feature creates a story that asks the audience to piece together the necessary information for themselves and infer the characters’ motivations. For the most part, this technique is used effectively, but the film is unclear in what it wants its audience to think. This becomes confusing and ultimately disengaging.

Disengagement is the biggest issue that “Sweet Country” will probably face with American audiences. The subject of racial prejudice is universal, and the western genre is still favorable to audiences, but the Australian culture and language is foreign. If you combine this with the film’s meditative and rarely intense pacing, lack of musical scoring and historic setting, audiences may lose interest midway through the film. “Sweet Country” does have the potential to hold its own ground due to its originality , and may ultimately foster a global conversation about Australia’s mistreatment of indigenous people.

“Sweet Country” opened at IFC Center on Friday, April 6.

Email Yianni Sines at [email protected].