Paul Auster Considers Conflict and Authorship in Discussion About New Book

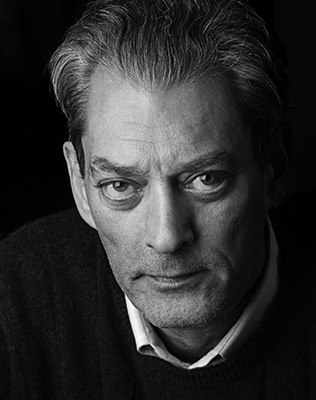

Paul Auster, author of “4321.”

February 28, 2018

On Thursday evening, acclaimed author Paul Auster spoke at Symphony Space about dichotomy, adolescence and his recently released novel, “4321.” Actor Michael Stuhlbarg — who is featured in three of the current Best Picture nominees — was also present at the talk. He did an extensive dramatic reading from the new novel.

“4321” tells the story of a boy named Ferguson born in 1947 whose life takes four separate fictional paths that run simultaneously. Four versions of the exact same boy live four parallel lives that are completely different from one another.

Stuhlbarg’s reading kicked off Thursday’s event and was a true highlight. The selection he performed from “4321” set the tone for the evening. It told the story of one Ferguson as an adolescent, struggling to find his rhythm as a young author. Stuhlbarg was articulate, captivating and affable. His acting prowess was demonstrated by his flawless portrayal of (one version of) Ferguson — bringing Auster’s voice to life for the audience.

Aside from a few comments about the length of the book and its personal significance to him, Auster mostly took themes from Stuhlbarg’s selection and augmented them to talk more broadly about the writing process and his goals.

Todd Gitlin, an author and scholar himself, moderated the discussion. His temperament balanced Auster’s well, and their discussion flowed naturally.

Auster and Gitlin discussed one interesting issue raised in the passage that Stuhlbarg performed concerning two opposing impulses in a writer: the impulse to control and the impulse to take risks. Stuhlbarg read from the novel that “all control [leads] to an airless, suffocating result. All risk [leads] to chaos and incomprehensibility. But put the two together and then maybe [you’ll] be onto something.”

Another schism mentioned in Stuhlbarg’s reading that Auster later discussed was one between the familiar and the strange, and an author’s difficult task of finding a balance between the two in his subject matter. If books are too familiar, Auster explained, they don’t teach you anything, but if books are too strange, they teach you things you don’t need to know. Authors, Ferguson and Auster included, want book plots to hang in a perfect balance between the familiar and the strange, as, according to Auster, this is the formula for a successful story.

One quote chosen by Gitlin for discussion included an ingenious metaphor used in the new novel — an enduring metaphor that explains the relationship between the individual and the world. Auster describes this relationship in terms of concentric circles, with the individual at the center and many coaxial, increasingly large circles — representing his university, his country, the world — surrounding him.

Gitlin probed Auster with an uncomfortable question, asking what Auster feels are some failures within his new book. After audience members voiced their disapproval at the question’s unfairness, Auster diverted the question somewhat, saying that this was up to his readers to decide.

The talk finished with a brief conversation about being a writer and the writing process, a process which Stuhlbarg’s selected reading documented Ferguson struggling with. Auster made his audience laugh as he added yet another dichotomous conflict to the list of ones already discussed: the constant back and forth between disgust at your work and looking at it and thinking it “actually doesn’t sound so bad.”

Paul Auster is the author of “The New York Trilogy,” “The Book of Illusions,” “Moon Palace” and “Invisible,” among other widely known works.

According to Auster, uncertainty lies underneath the surface, with all these ubiquitous dichotomies, and also above ground, with something as simple as the success of a novel being up in the air.

“The writer is the last one to judge his or her own work. It’s for other people to decide,” Auster said.

Email Emily Fagel at [email protected].