Culture in the Context of Chinese Communism

Soon to be launched on Netflix, “Sky Ladder” originally premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival and focuses on Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang.

October 13, 2016

“Sky Ladder,” Kevin Macdonald’s new documentary about Chinese artist Cai-Guo Qiang, is a thoughtful look into his expansive pyrotechnic work. It also touches upon the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the mixing of art and politics and the meaning of art.

Qiang was born in Quanzhou, a city whose history is rooted in the philosophical system of Feng Shui. When Qiang was nine, the infamous Communist revolutionary and founder of the People’s Republic of China Mao Zedong launched what became known as the Cultural Revolution. The movement aimed to “purify” Chinese culture by purging anything related to capitalism or traditional, feudal eras. Qiang’s father, a calligrapher, spent all his money on books. But during the Cultural Revolution, he was forced to burn them all. For three consecutive nights, Qiang helped his father throw them into the flames, watching them become a heaping pile of ash. In the film, he started crying as he recalled this painful memory.

This narration throughout the film is not just poignant, but also successfully shows the Chinese state’s relationship with art and connects seemingly disparate events in a way that explains Qiang’s trajectory. During the period of liberalization following Mao’s death, people would say to Qiang, “although you’re a hardworking artist, it is not possible for you to surpass Picasso.” He would reply, “Why can’t I surpass Picasso?”

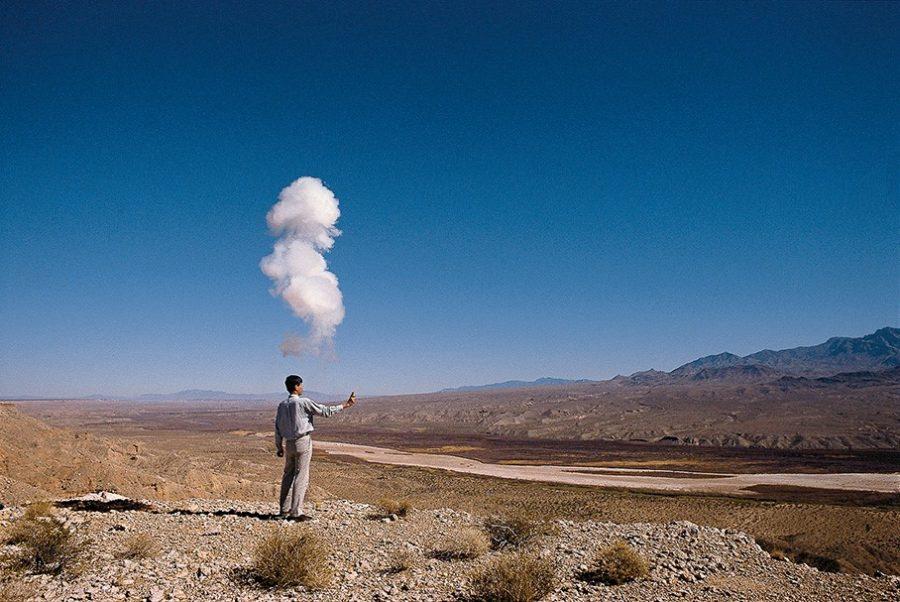

“Sky Ladder” is a good primer for people unfamiliar with Qiang’s art, but it is also a work of depth that questions what art is. One of Qiang’s styles involves taking his existing canvas works and igniting them with gunpowder, boldly making the moment of explosion into art. This particular style, one that favors spontaneity over organization, was inspired by his father’s calligraphy. Macdonald shows his audience many of these explosions, leaving viewers in awe as existing artworks are destroyed while new ones are created from the ashes.

Qiang was first noticed on a large scale after he created a fireworks exhibit in New York in 2003. Since then, he has become a renowned artist who has been employed by big organizations for grand projects. One such sponsor was the Chinese government, who taped him to choreograph the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics.

Macdonald takes this project and uses it to explore the dilemmas artists face when they get tangled up in politics. As was expected, soon after Qiang took on the project, he faced a bureaucratic hurdle. He wanted to use environmentally friendly products, but the government did not agree, thus forcing him to put aside his values. Moreover, by taking on this assignment, he was voluntarily taking part in state propaganda. People questioned his decision, and even his strongest supporters did not appreciate it.

In spite of all his accomplishments, Qiang had not fulfilled his strongest wish: to create a “Sky Ladder,” a ladder-shaped line of fire that touches the sky. Part of this stems from his upbringing in Quanzhou and a longing to connect with the unseen (in this case, whatever lies beyond this earth in the vast reaches of space), but it is principally driven by his love for his grandmother and desire to show her a great spectacle. After trying thrice in the past two decades and failing, he finally succeeds in creating it during the final moments of the film. The display is as brilliant as it is indescribable, but Macdonald expertly places us at the center as a trail of fire burns through the night sky. It is a fitting final scene that captures the effort of Qiang’s phenomenal journey and ends a wonderful documentary.

Email Ali Hassan at [email protected].