Wagner student to speak at UN

September 29, 2014

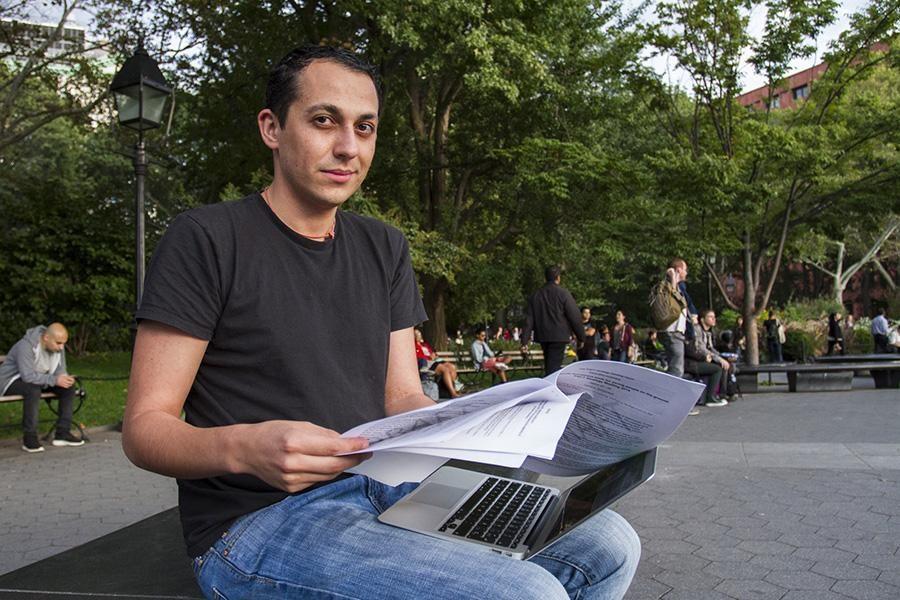

Aram Barra, a student of Wagner’s Global Executive MPA, is pioneering change on drug legalization policies worldwide.

Barra has been invited to the 2016 U.N. General Assembly Special Session, which will focus on drug policy.

“My job will be to speak to all the nations to help define a position, question their current position or identify why they agree or disagree with certain policies,” Barra said.

Barra has garnered a range of experience working with various international organizations, including the British think tank Transform Drug Policy Foundation and Mexico-based Mexico United Against Crime.

He has advised countries including Mexico and Uruguay in past U.N. assemblies to simplify the complexity of drug policy in a global platform.

“I act as the officer for Latin America to foster reform across the continent of the legalization of drugs including cocaine and cannabis,” Barra said.

The reform that Barra wants is part of his effort to create a community of like-minded countries that support change in policy. The issue at hand is focused on two main arguments: the proportionality of prison sentences and whether current international conventions serve their purpose.

Barra called for a consensus among all nations on a unified drug policy to alleviate inconsistency between legality and prohibition.

“In Latin America, more women and young people are prosecuted and imprisoned for small-time trafficking, while only halfway around the globe, in North Africa, parts of the Middle East and of Southeast Asia, individuals are subject to the death penalty,” Barra said.

An international classification deeming drugs as being useful or not is yet another discussion in the labyrinth of drug policy, he explained.

“It’s not only confusing, but also not fair that there are countries that are producing, other countries that are prosecuting and some with both aspects,” Barra said.

Specifically, Barra referred to Mexico as a country that is ineffectively prosecuting individuals for simple possession crimes.

“It’s a bad policy because it distributes resources poorly, criminalizes people who are not upping the ladders of organized crime [or a] bad influence to society,” Barra said.

Barra explained that the overemphasis on prosecution does not equally distribute federal money to fund health programs. Therefore, resources are not used efficiently for a suitable drug policy.

Barra spoke highly of Uruguay’s current model, which imposes three methods of regulation instead of simply relying on prosecution. Although Barra is optimistic about using Uruguay’s drug policy as a model for other countries, he acknowledged that conservative governments will be less likely to welcome reform. However, a growing number of like-minded countries have made clear that the international law should be responding to the current circumstances of the drug policy.

“Policies need to be effective and efficient and bound by human rights,” Barra said. “When we start putting moral arguments before policy, policies usually end up being bad policies.”

Barra spoke about how he envisions an international drug policy that will ensure fair standards and uniformity.

“I really hope countries move to regulating with drugs, beginning with cannabis and ending with all drugs,” Barra said. “I would like to see a world where an individual that uses drugs is not criminalized.”

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, Sept. 29, 2014 print edition. Email Nina Jang at [email protected].