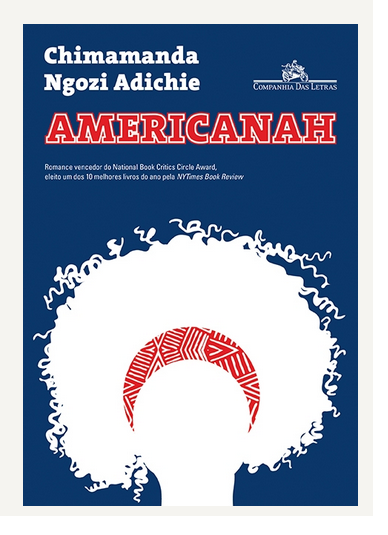

Book Review: ‘Americanah’ by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is CAS’ required summer reading, telling the story of a young Nigerian woman pursuing her education in the US.

August 28, 2017

I did something unthinkable this summer — I read the Class of 2021’s required reading, “Americanah” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, for pleasure. And I would recommend for everyone else to do the same.

Each year the College of Arts and Science assigns a book to incoming freshmen as a part of the First-Year Dialogue Program. Usually my pulse quickens at the thought of mandatory reading, but the books selected seem focused on enriching social views and opening discussions on diversity, race, and identity that can often be easier to avoid than to confront. Last year, I was pleasantly surprised by the university’s selection of “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nahisi Coates. This year, I once again found myself floored by NYU’s choice of the eye-opening work of Adichie with her beautifully written, achy and tender novel, for which she won the 2013 National Book Critics Circle Fiction award.

Americanah illustrates the ebbs and flows of life for Ifemelu, a Nigerian woman who moved to the United States for college after a series of strikes at her university in Nigeria. Readers watch carefully as she adjusts to life in America and afterwards as she struggles with finding her identity among the many chaotic voices around her.

Throughout the novel, the reader notices frequent and ongoing instances of both intentional and unintentional racism directed toward Ifemelu. We watch helplessly as she and other people of color are discriminated against in the workplace, in the dating field, at university and generally in day-to-day life — sometimes by well-meaning, but ultimately ego-centric, Americans, sometimes by those who are simply ignorant and hateful and sometimes even by other people of color.

What hurts the most about this book is that although it is fiction, it is real.

It’s impossible to truly understand what someone else’s life is like, but Adichie paints an extremely thorough outline. One particular scene where Ifemelu is taking the train to an inconveniently distant area of New Jersey to get her hair braided stuck with me in that it demonstrates the genius of Adichie’s subtle tone and peppered anecdotes. Ifemelu is annoyed by the distance that she has to travel to find a salon where she can get braids but ultimately comes to the conclusion that it would be unreasonable to expect such a place nearby with so few black locals in Princeton. A few moments later, she notices a man at the train station eating ice cream:

“The man standing closest to her was eating an ice cream cone; she had always found it a little irresponsible, the eating of ice cream cones by grown-up American men, especially the eating of ice cream cones by grown-up American men in public.”

The contrast between the life of Ifemelu and that of this man is just one piece of the puzzle that Adichie nudges toward her readers in “Americanah” — the puzzle composed of race, privilege and the destructive fist of American identity, a puzzle which explains how this country is wired to build some people up and knock others down. She is not asking for pity, she is spelling out the truth.

However, Adichie is careful not to make this the central plot of the novel. Although the world around Ifemelu does not aid in her original transition from Nigeria to the United States, the story is about her personal identity, the universal search for love and the reality of life in America for immigrants. Having moved to this country only recently myself, I couldn’t help but choke back emotions when Ifemelu describes her first few days in Manhattan, seeing my own reflection in her thoughts.

It saddens me to think of all the slick freshmen who decided to bypass this reading and blunder their way through the group discussions. It saddens me to think that the puzzle will remain deconstructed before their eyes.

A version of this article appeared in the Sunday, Aug. 27 print edition. Email Jemima McEvoy at [email protected].