The Brock Turner Law Won’t Catch Privileged Rapists

September 7, 2016

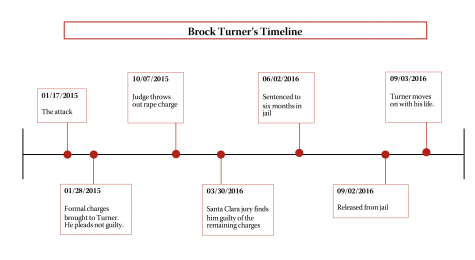

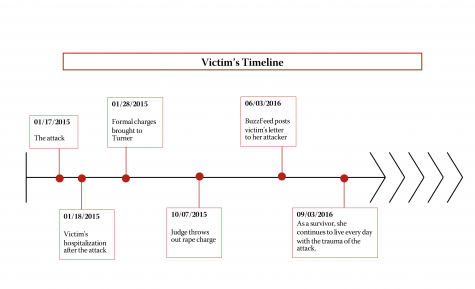

Brock Turner — former Stanford swimmer, convicted rapist and one of the most hated men in America — was released from prison after serving only three months of his already short six-month sentence. Outrage swelled again after his release, prompting the California legislature to rectify what many saw as a legal loophole allowing Turner to go free far short of the original 14 years he was facing in prison. Previously, there was no mandatory prison time for sexual assaults committed “without force,” or in instances where the victim cannot actively resist assault. The State’s amendment would add a mandatory sentence of three years for those convicted of this type of assault.

While the move, on paper, seems like a strong statement by the State assembly to address an issue sexual assault activists have been lobbying for years, it still falls short of tackling the heart of rape culture and has the potential to victimize the wrong people. Instituting mandatory minimums, for example, is not a foolproof method for reducing crime. People of color, especially African-American men, are incarcerated at a much higher rate than their white counterparts for crimes that have mandatory sentences such as drug possession. Once incarcerated, African-American men can be trapped in a cycle of poverty that can cripple future economic prospects.

The fallout from mandatory minimum laws hardly fits the profile of Brock Turner’s life: white, educated and with a sizable family war chest to pay off any necessary lawyering fees. Amendments like the one the California legislature just passed often have a disproportionate effect on people of color. While rape is a crime that should be punished irrespective of who commits it, there are enough opportunities for privileged rapists to escape the consequences of their actions to render the laws ineffective. Legislatures should take care not to confuse simple band-aid fixes like harsher penalties with proactive solutions to a complex and multifaceted issue.

If the Legislature were interested in dealing with rape culture head-on, it should look into laws that increase the culpability of college administrations, both public and private, when rapes are committed by their students. Landmark legislation such as the “Yes means Yes” consent bill mean that California is taking steps to make their state system work in favor of rape victims, but getting to the point of reporting a rape to law enforcement can be a harrowing process for students fighting against universities that are eager to protect the reputation of their institutions. Creating an environment where rape culture itself is shunned on campuses and among all students, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, is key to stemming the tide of assaults carried out by privileged men like Brock Turner.

Opinions expressed on the editorial pages are not necessarily those of WSN, and our publication of opinions is not an endorsement of them.

Email Emily Fong at [email protected].