‘Man in High Castle’ weak overall, but has its moments

Amazon’s new series, “The Man in the High Castle”, offers a unique perspective on what life would be like if the Nazis won World War II.

November 30, 2015

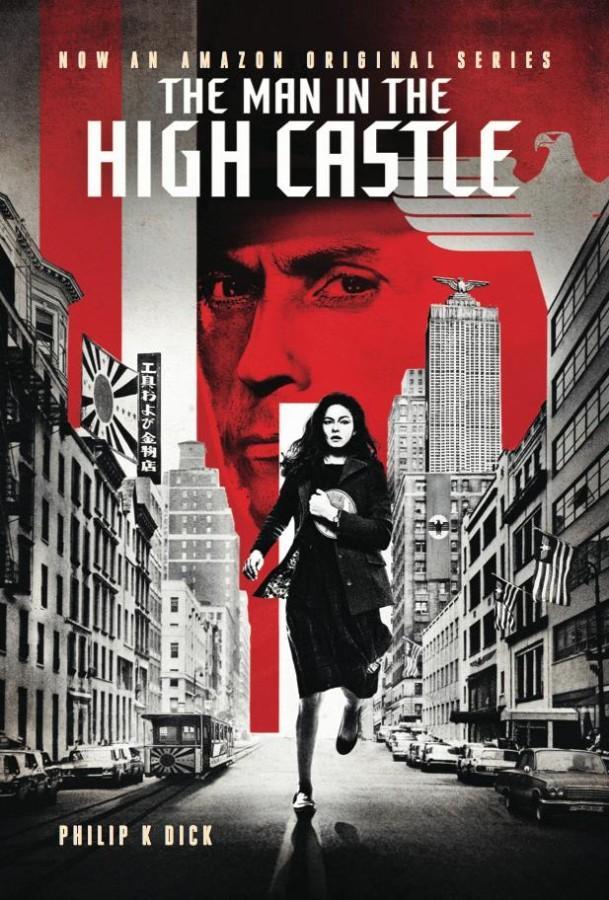

Amazon released the first season of “The Man in the High Castle” on Nov. 20. Based on the Philip K. Dick novel, “The Man in the High Castle” imagines what life in the 1960s would have been like if the Axis Powers had won World War II, thus making it Amazon’s most ambitious and longform original series to date. The program comfortably lands in the same tier as Amazon’s best shows, “Transparent” and “Catastrophe.” It utilizes its unique premise for solid entertainment, and though it hits a few rough spots due to sloppy plotting, it still satisfies by sharply tackling big ideas, most of which concern art’s relationship to power and humanity. The show makes artwork the most valuable measure of power.

While many small storylines comprise the first season, they ultimately form two major narrative threads. The first involves a Cold War-like struggle between Japan and Germany’s leaders, with the United States serving as the conflict’s battleground — think Germany after World War II. The second storyline centers on a trio of characters, Juliana Crain (Alex Davalos), Frank Frink (Rupert Evans) and Joe Blake (Luke Kleintank), who through chance events end up working for subversive groups trying to weaken or topple the Axis Powers.

At times, “The Man in the High Castle” struggles to organically develop these storylines. The plot often spins its wheels, especially halfway through the season when the character’s motivations and actions aren’t always clear aligned. Even though the show’s storytelling isn’t smooth, it manages to be tense, even gripping. Additionally, the cast is sublime; the actors bring humanity to their characters, allowing viewers to empathize with them even when the plot is weak.

However, what’s most compelling about the constant fighting between the Germans, Japanese and subversive groups isn’t the tension produced, but the objects they fight over. These three groups don’t chase after weapons, nuclear bombs or confidential reports, but after artistic works. The three groups believe that films, books, paintings, music, costumes and other artworks are the best weapons in a power struggle because they can subtly influence the ideological values of the masses.

By having its main characters obsess over artistic works, the show serves as an astute examination of how art can serve power or undermine it and how it can oppress people’s minds or free them. But the show never reduces art as a weapon; the program is sensitive to art’s relationship with humanity, how it can allow them to bond, grieve, hope and even risk their lives for others.

A version of this article appeared in the Nov. 30 print edition. Email Akash Shetye at [email protected].