The true costs of social work education

April 8, 2015

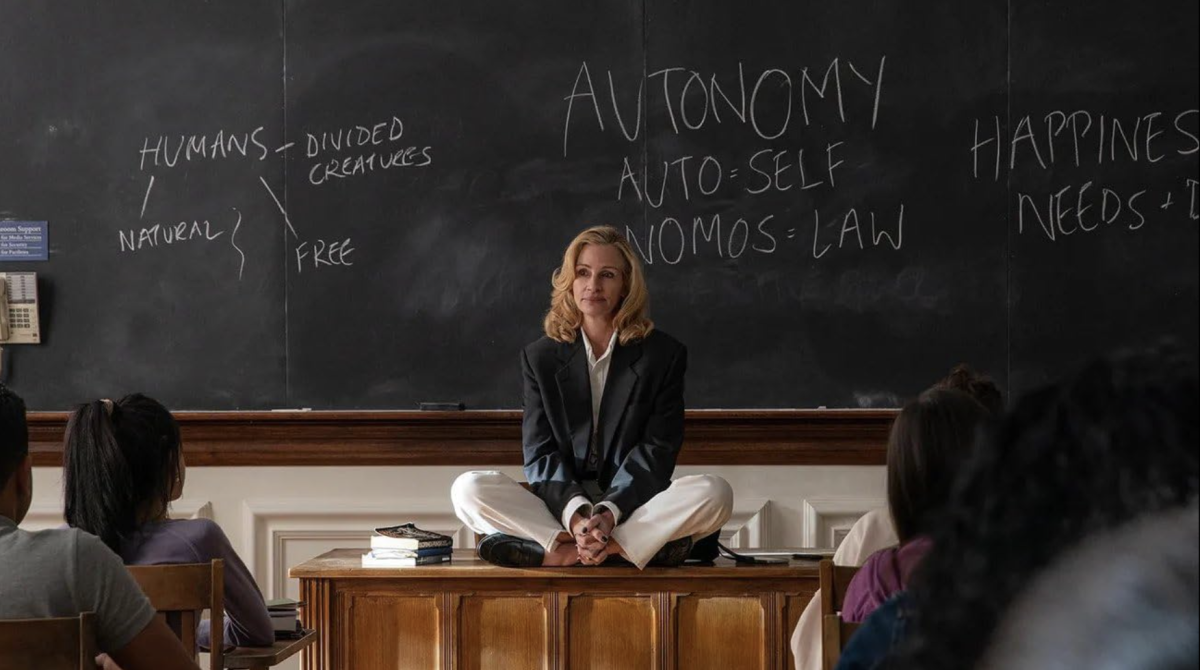

Master’s students at the Silver School of Social Work are trained to find biases within themselves that mirror the injustices of society as a whole. This ability to turn awareness inward, they are taught, is crucial to ethical social work practice. But in the face of inequality and biases in its own system, the Silver community is largely silent.

Silver students, administrators and faculty need to start talking about how the current structure of social work education goes against the field’s efforts to change society’s larger inequalities. It is time to confront the true costs of social work education. Chief among them are those of money, time, and equality of opportunity, which impact not only students but clients and the field as well.

First, the monetary costs: high tuition for social work Master’s programs is leading many students into debt.” Silver offers a variety of financial aid options to cover its more than $35,000 a year tuition, but none amount to a full scholarship. National median debt at graduation for MSW students is $32,198, while the median salary of a social worker with over 30 years of experience is only $63,000. An educational system that asks students to take on substantial debt in exchange for low financial returns does not combat economic inequality.

Next, the costs in time: MSW programs include mandatory, unpaid field internships three days a week. Students pay for these credit hours. Field internships are a component of all accredited social work programs, not just NYU, even though empirical evidence supporting their usefulness is limited. This arrangement makes it incredibly difficult for MSW students to engage in any additional paid work, let alone enough paid work to cover tuition or living expenses. For a profession devoted to expanding opportunities for oppressed groups, social work sets an awfully high economic barrier to entry for its own practitioners.

Together, these high costs introduce an even higher one: the price paid by all when the expenses of social work education translate into reduced opportunities for members of racial minorities. Data shows that black and Hispanic families in the United States continue to make significantly less than white families and that student loan debt has an especially negative impact on lifetime wealth for minorities. MSW programs’ expensive, time-consuming structure likely bars many of limited financial means from entering the field, and the above data suggests that we effectively bar racial minorities as well. It is unsurprising, then, that social work is dominated by white practitioners. Despite its mission of making society more inclusive, the structure of social work education makes the profession most feasible for white people, who already hold more than their fair share of power.

Ultimately, social work passes these collective costs on to clients. While field placements can provide positive experiences for everyone involved, many agencies where students intern lack sufficient funding and staff. As a result, students—whose prior clinical knowledge may be negligible—are sometimes overworked and under supervised. Clients, who often come from populations that are already marginalized, shoulder the brunt of these flaws when the people meant to help them lack the time, energy or professional support necessary to provide quality service. Clients may walk away unclear messages about what level of care they deserve, or worse, without having their immediate needs met. By helping perpetuate these conditions in agencies, the structure of social work education again seems to support the oppression of disadvantaged groups rather than combat it.

These costly realities would be troubling in any field, but the combination of all of them in the field of social work is devastating.

The first step in confronting these complicated issues is to acknowledge them openly as a community. This dialogue should begin at Silver not because NYU lags behind its peers but because it can lead by example. There are no easy solutions to these problems, but through collaboration the status quo can change. NYU says it is “a private university in the public service,” and for Silver to live up to that claim, it is time for this conversation.

Opinions expressed on the editorial pages are not necessarily those of WSN, and our publication of opinions is not an endorsement of them.

Liz O’Connell and Hannah Sheldon Dean are both current second-year students in the two-year MSW program at the Silver School of Social Work. Email them at [email protected].

Bryan Meisel • Apr 16, 2015 at 10:48 am

Thank you for writing this article. I have tried to discuss this in multiple classes and often find myself silenced and dismissed by my professors who tell me that my 21 hours of work each week is just “educational experience” and that my work amounts to the value of the supervision I receive.

Furthermore by being abuse to use interns as free labor, we are making it harder for us to get jobs out of school. My supervisor last year, a LMSW, was laid off and replaced by two MSW interns. Whoever wrote this article, please reach out to me. I’d love to speak with you in person.

Keba grazette • Apr 15, 2015 at 10:34 pm

I totally agree, the discussion need to take place about MSW students who have worked in the field and is experienced and still have to do field placement. I believe if you are experienced in the field, internships are not necessary. I am wasting my time doing field I feel like free labor and a extra pair of hands. I am paying childcare to do a unpaid internship and paying to be graded from an internship supervisor with a MSW that have power struggles. Why are we paying to do free labor?