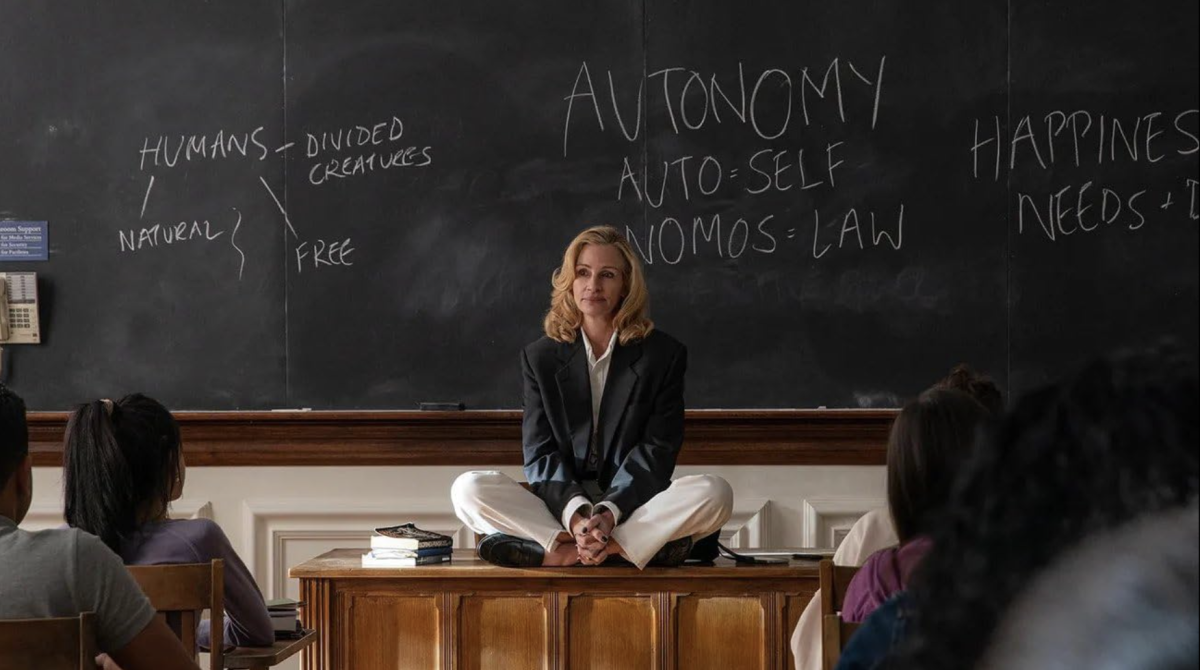

The phrase “art cinema” might traditionally make you think of a director whose films are restrained and refined — the films of a European director like Michelangelo Antonioni or Michael Haneke. But in a time where digital technology is replacing film stock, tradition matters little.

Art cinema is changing, too. Sixty years ago, audiences might have cringed at the thought of something like Baz Luhrmann’s “The Great Gatsby” being called art, but today, it’s normal for big, bold and extravagant entertainment to praised. Even “Pain & Gain” found a few critics who could embrace the film as a subversive art object.

Recently it seems that studios are more willing to fund even the most over-the-top efforts. Films like “Gravity” and “Man of Steel,” which bare the stylistic stamps of Alfonso Cuarón and Zack Snyder, both had triple-digit price tags. Neither was guaranteed to do as well as they did — both were risks in their own right.

Even if an auteur wants to make an extravagant epic, it’s possible to do that outside of the studio system. “Cloud Atlas,” a three-hour romp through time from Andy and Lana Wachowski, cost over $100 million and was entirely independently financed.

VOD and iTunes have also allowed auteurs to make over-the-top films that would never find mainstream audiences. A film like Brian De Palma’s “Passion,” despite featuring big-name headliners Rachel McAdams and Noomi Rapace, could have never succeeded theatrically due its bizarre mix of lesbian sexuality and violence, but because of its VOD release, the film found its audience.

Most importantly, it’s been the intermixing of high art and low art in the past 30 years that has allowed auteurs to take their films to baroque places. Combine a tale of loneliness with Avicii, and you’ve got Sofia Coppola’s “The Bling Ring.” Mix the wryness of a David O. Russell screenplay with the campiness of Bradley Cooper with a Jheri curl, and you’ve got “American Hustle.”

If studios were this daring 60 years ago, who knows what sort of amazing creations could’ve been made? Without these risks, this year could not have had the spectacle of “Gravity” or the extravagance of the gyrating bodies in “Spring Breakers.” In both cases, we can be thankful that studios are so willing to let filmmakers make such excessive films.

Alex Greenberger is film editor. Email him at [email protected].