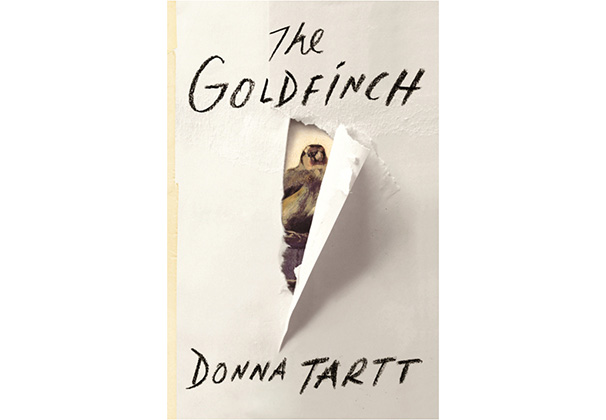

It has been 11 years since Donna Tartt last graced the literary world with her dominant prose, and her return to the bestseller shelves and to the hearts of readers worldwide proves nothing less than spectacular. Her two previous novels, “The Secret History” and “The Little Friend,” established Tartt as a master of detail and storytelling, but her third book may be her best yet.

At just over 770 pages, “The Goldfinch” begins in New York City and chronicles the life of Theodore Decker. The story opens on the most pivotal day of his early adolescence and ends as he reaches adulthood. Tartt’s conversational yet elegant prose prevents such a large book from feeling too dense. The piece is told from Theo’s poignant point of view, as if he is telling this story just for the reader or for anyone who is willing to hear it.

He recounts the rainy afternoon he and his mother, through a series of fateful encounters, decided to go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As his mother shows him a painting she had always admired, titled “The Goldfinch,” the museum is bombed, and Theo’s mother becomes one of the many casualties. When he regains consciousness among the rubble, Theo briefly chances upon a dying museum-goer, who gives him a ring and directions to deliver it. Hastily, Theo agrees to this request and grabs his mother’s favorite painting before escaping the debris. He is alone, without a parent and with little more than a strange ring and a stolen artwork. Theo’s gripping tragedy unfolds as this scene sets the precedent for the rest of his life.

Devoted to her protagonist, Tartt guides the reader through Theo’s reactionary lifestyle, as he returns the ring and is subsequently introduced to new friends, a new home, his previously absent father and other twists of fate. The scenes and the characters change rapidly, but the two constants are Theo and the stolen memento of his mother. Various storylines and connections sprout from Theo’s life — some that thrive and some that fade. But the painting, his symbolic burden and reminder of his past, always remains.

Most importantly, the reader always cares about Theo, a nihilistic and deeply flawed character who endures unrequited love, unbearable guilt and a drug addiction, all of which resonate with some of the hardest aspects of being human. He is a fully three-dimensional character, an appealing yet gritty individual struggling to find peace and truth in a life plagued by chance, both beneficial and detrimental. His universal struggles make him so sympathetic.

“The Goldfinch” is a striking text. While it is by no means a quick read, it will certainly feel like one. Through intense and effective development, Tartt ensures her audience cannot forget the character she has created. Indeed, once the reader has endured Theo’s struggles alongside him, it is impossible to shake the experience in the wake of such a thrilling tale.

A version of this article appeared in the Wednesday, Nov. 6 print edition. Mary Hess is a contributing writer. Email her at [email protected].