As one doctor says in Martha Shane and Lana Wilson’s controversial documentary “After Tiller,” “no one wants an abortion.” Many of the patients in this documentary about abortion are couples who are terminating planned pregnancies after testing revealed deformities that would severely handicap the life of their child. One story presented early on is that of a college student who was raped.

If these stories are any example, “After Tiller” is by no means a simple film, and it offers a new angle on abortion, a polarizing topic that has been examined in just about every way imaginable.

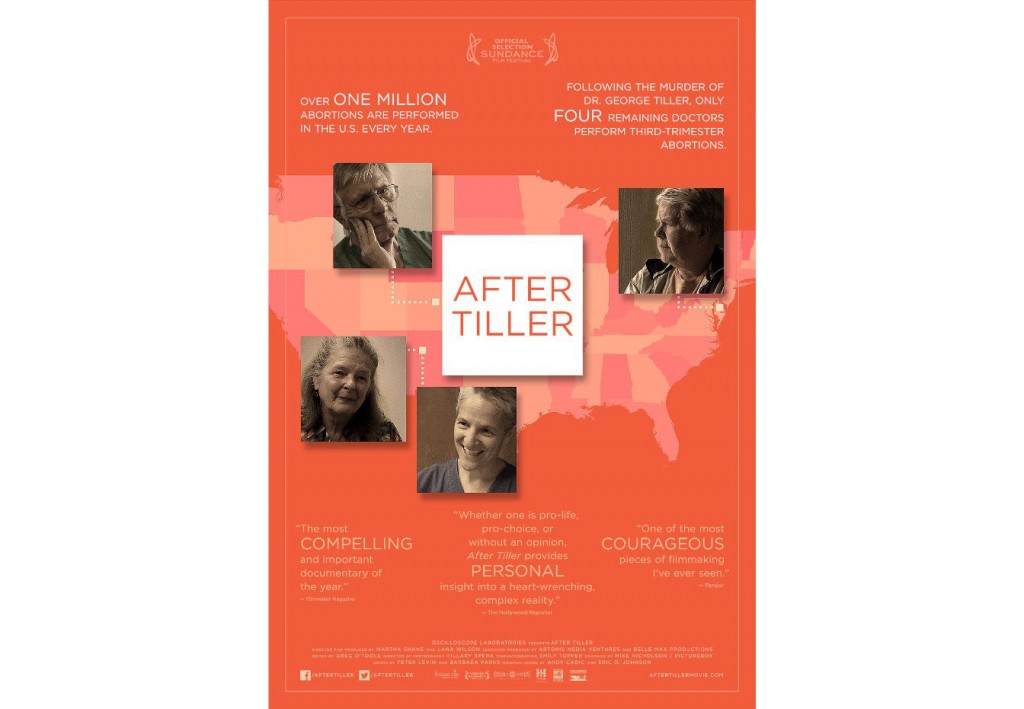

In 2009, Dr. George Tiller, while serving as an usher during a church service, was shot by anti-abortion activist Scott Roeder. Upon his death, only four known doctors in the United States performed late-term abortions. Each of those doctors appears in the documentary, sharing their insights — they only complicate the matter further.

From the opening scenes, “After Tiller” delves into the layers that the four doctors have dedicated their lives to unraveling. Shane and Wilson are invited behind the doctors’ closed doors, where patients tearfully describe their situations. The doctors and their staff not only describe the procedure or examine other options (in various cases, doctors recommend adoption), they also counsel their patients. When one patient says she cannot face her family and friends, one doctor advises her on exactly what to say. Another doctor embraces a woman and sends her home with a box of tissues.

Although the technical side of “After Tiller” is not outstanding, there is enough ingenuity in the way Shane and Wilson approach the emotional conversations like these to make the film worth viewing. By focusing on the doctors and their emotions, the film humanizes a group of people who are often the target of death threats – and that in itself is a remarkable achievement.

As the film continues, the complexity deepens, as the doctors do not permit abortions to every patient. The decision is never easy, especially when they consider the drastic measures a rejected patient may take. Unfortunately, Shane and Wilson do not dedicate an adequate portion of the film to showing how the doctors make these difficult decisions, instead showing patients who have a “more compelling reason,” as Dr. Robinson says. Showing diversity in stories, instead of focusing on fetal abnormalities, could have given the film another layer.

Nonetheless, “After Tiller” could have easily been another political documentary about a hot button issue. Instead, Shane and Wilson present a topic that commonly triggers animosity and violence in a sensitive, intimate way that makes late-term abortion a humanist issue.

Be aware that “After Tiller” is not meant to be enjoyed — instead, it is a film that should be watched with an open mind. After viewing the film, it’s very likely that your opinion might be different from the one you had before.

Marissa Elliot Little is a staff writer. Email her at [email protected].