As the sequel to the beloved “BioShock,” the expectations for “BioShock Infinite” reached unprecedented heights. Overall, the game and its immersive world do not disappoint. However, while many feel this game is both a climax and conclusion to the Xbox 360-PlayStation 3 generation, “Infinite” nonetheless shares many problems common to this era.

“Infinite” takes place in Columbia, a city above the clouds claimed by its inhabitants as “heaven, or as close as you can get.” Entry into this steampunk metropolis necessitates a procession through a monolithic Gothic church and an idealized Roman garden, following a spiritual rebirth via baptism. Yet the game juxtaposes such imagery against the reality of Columbia’s clearly degenerate society.

The player witnesses a world full of patriarchy, capitalist decadence, class struggle and racism. Indeed, all of the religious imagery serves as propaganda to consolidate the rule of Columbia’s so-called prophet, Zachary Hale Comstock. Tackling such heavy themes is a rarity in gaming, giving “Infinite” an artistic depth generally unseen in mainstream releases.

All of these concepts serve as a devastating critique of American culture. While this analysis seemingly attacks America’s past, it nevertheless feels resonant.

“Infinite” is a complete departure from the undersea setting of the original “BioShock.” Unlike the dark and dilapidated Rapture, Columbia consists of bright colors and a heavily populated world. Having normal human beings going about their business until catastrophe strikes serves to make the world of “Infinite” feel truly alive and captivating.

Nevertheless, issues with the structure of “Infinite’s” gameplay detract from the impact, ultimately revealing a crucial problem inherent in the gaming industry. As “Infinite” is a first-person shooter, the player often will find himself engaged in combat. While the structure of this aspect of play shares much in common with the original “BioShock,” it has been greatly refined and polished for better gunplay. However, shooting sections happen far too often, to the point where they begin to feel mundane. Unfortunately, this, too, often inhibits forward action instead of contributing to a sense of tension.

“Infinite” falls into a problem common to all first-person shooters — there is too much shooting and not enough of everything else. The parts where the player can explore the characters through puzzles are pushed aside because of all the gunplay. The puzzles are optional due to fear that anything besides shooting would not appeal to a mainstream audience.

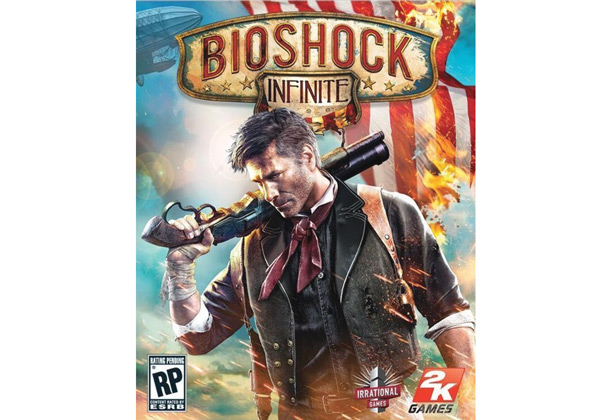

Considering “BioShock’s” immense reputation and guarantee of stellar sells, it is disappointing that Irrational Games did not take more risks. Less shooting and more exploration would have served to heighten immersion and the impact of the game’s themes. Even so, “Infinite” still astonishes and stands above other shooters for its artistic depth.

A version of this article appeared in the Tuesday, April 2 print edition. Devon Hersch is a contributing writer. Email him at [email protected].