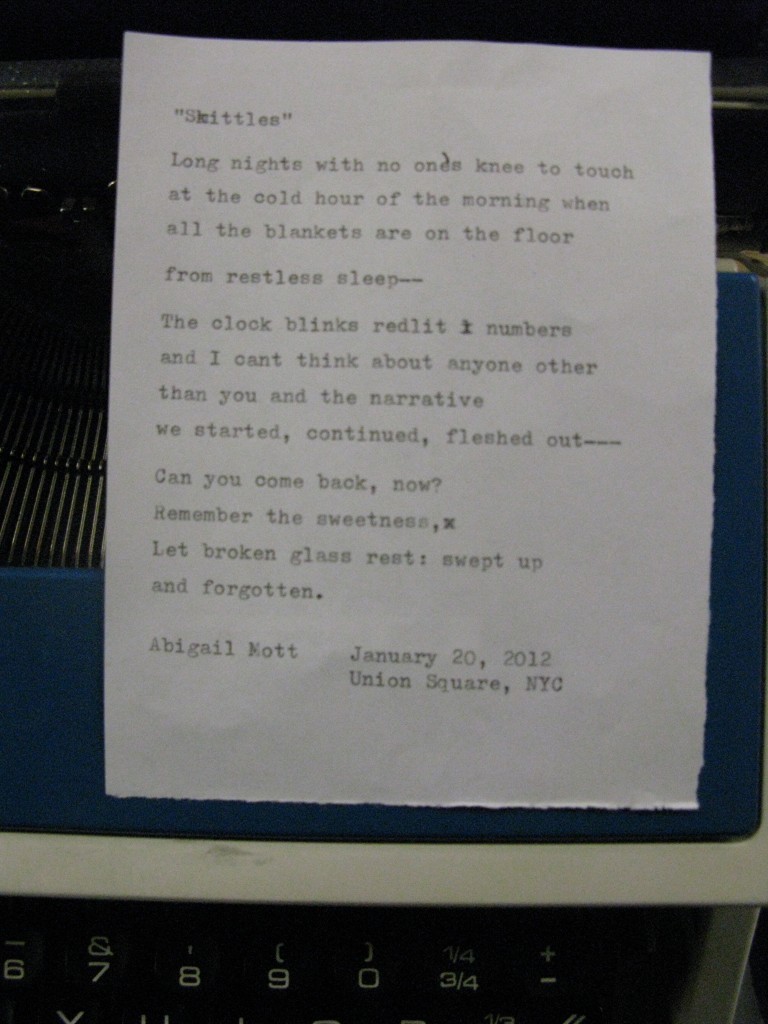

Clickety, click, click clack. The ribbon spool adjusts and the typebars dance. Clickety, click, click. Ticking stilettos and tapping loafers collide and clash. Click, click, clack. Abigail Mott’s fingers flutter over her typewriter as if tickling an instrument. And as she plays instead of notes, words of poetry fill the page line by line.

As the great poet Jean Cocteau once said, “The poet doesn’t invent. He listens.” And in her little niche in an accented corner beneath the streets of Union Square, Mott looks and listens. Beside her feet, an unobtrusive yellow sign reads in Sharpied bold lines: “NAME a PRICE. PICK a SUBJECT. GET a POEM!!” A customer walks up, in hand a $20 bill.

“I would like a poem, for my wife,” he says shyly. “She’s a poet, too. She’d like that.”

Smiling, Mott slowly opens her little black briefcase and takes out a half sheet of paper. With a flow of her long fingers through her beaded necklace and a careful placement of her wrist, off she goes again.

There was something startling and disarming about that sight, especially to a twenty year-old journalist watching from afar. But was it the awe of realizing that she promised spontaneous art at the customer’s whim? Or was it seeing a fashionable young woman seated before an unfashionable bit of technology, producing a unique, tangible sheaf of poetry?

Hype today about the iPad 3, tomorrow about a new social media platform. Myspace, Twitter, Tumblr, WordPress. Digitalization excess. Perhaps in the whirlwind rush towards a wider World Wide Web, we’ve lost the individual. The human element has all but disappeared when you find rhyme generators and ‘instant poetry’ forms that allow anyone to ‘create’ a poem instantaneously. The LOLs and OMGs rhyme with :)s and XOXOs. In our digital world, what has become of what Mott believes to be the “ultimate form of expression?”

“The poet has the ability to make the poem like a musician makes a musical score,” said Matthew Rohrer, an English Professor at New York University who specializes in poetry. “We can control exactly the way it is read.”

Abigail Mott is just one example of a small group of young people harkening back to a seemingly slower-paced world. But the transition hasn’t been easy and cyberspace is making it much harder for younger aspiring writers.

To understand Mott’s quandary, one must understand her passion. For Mott, it all began with a chance encounter last year with a kindly gentleman on the streets of San Francisco. His vintage Underwood 315 typewriter and promise of spontaneous poetry mesmerized and pulled at her until she could resist no longer.

She approached him, and he explained. It was instant poetry to test his capabilities with a cash bonus on the side. And then he said the magic words:

“Hey, maybe you can do it.”

From there, her love affair with spontaneous prose began. Mott recalls the excitement building as she shared her new discovery with friends and family, and they soon became test subjects for her new, quirky talent. Then, the stage was set and together Mott and her friends organized her debut at the Golden Gate Park.

“I remember my first customer wanted a poem about the universe,” chuckled Mott. “So I wrote a tiny little poem. My friends would be yelling next to me, ‘She’s practicing, get a poem for free!”

Since last August, it’s been nine months into the project. And already worried siblings are badgering her with questions.

“When are you going to get a job? How are you making money?” Mott recalls her brothers saying. When asked how much money she makes, Mott simply replied, “Who knows? I don’t really keep track.”

But the truth is, Mott would never be able sell her poems on the Internet: people expect those for free. The streets of New York City are much kinder.

“I see something like this, and I think: ‘This is mine,’ you know? Created for me,” said Angela Kuan, 35, gently placing her poem in her bag. “You can’t Ebay that.”

My shock from encountering Mott at her wooden desk in the subway station will soon parallel the startling disappearance of all conventions and rituals that accompany poetry-writing. They will fade just as the quill and candle have faded, as the typewriters and dictionaries have faded. But what will happen to poetry itself?

“It will be the same, no matter what kind of machine people write it on,” said Rohrer. “I think platforms like flash player and such where the poems sort of unfold on screen in front of you are basically ridiculous fads, and don’t and won’t help readers with poetry. Poetry already has an incredibly successful and perfect format: the poem.”