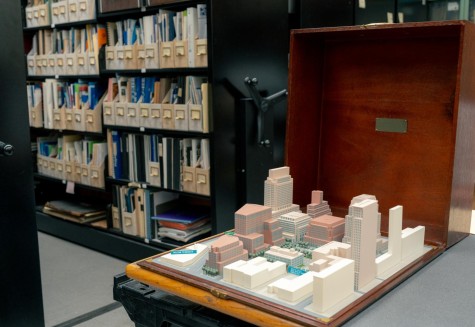

Most of NYU’s schools are concentrated around Washington Square Park, in the heart of the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan — surrounded by historic brownstones and luscious greenery. The Tandon School of Engineering, however, is across the East River, in an area known as the MetroTech Center in Downtown Brooklyn — characterized by the facades of former corporate buildings and underdeveloped outdoor spaces. Brooklyn has always been a place where different social groups have mixed and mashed, creating a rich history of culture and change. But among MetroTech’s early ’90s corporate buildings, that can be difficult to see.

The area first became a college campus in 1957 when the Polytechnic Institute — originally built on Livingston Street, where it remained for a century — moved into 333 Jay St., previously an American Safety Razor Company factory. At the time, NYU had two campuses — Washington Square in Greenwich Village and University Heights in the Bronx. The University Heights campus housed the College of Arts & Science and the College of Engineering.

In 1971, NYU was experiencing mass amounts of debt and the increase in crime in the city of New York deterred out-of-state students from enrolling at the university. To remedy the university’s financial struggles, James Hester, who was at the time the university’s president, put the University Heights campus up for sale. In 1973, NYU moved its Bronx programs back to Manhattan, and the Bronx Community College took over the University Heights campus.

In 1973, the Polytechnic Institute acquired NYU’s College of Engineering after NYU sold its University Heights Bronx campus. Finally, in a gradual process from 2007 to 2014, the school merged with NYU again and in 2008 renamed the NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering and in 2015 to NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering.