Review: ‘In the Margins’ imagines writing without writers

Elena Ferrante’s new craft-based book demands that contemporary literature rely only on the merits of its prose.

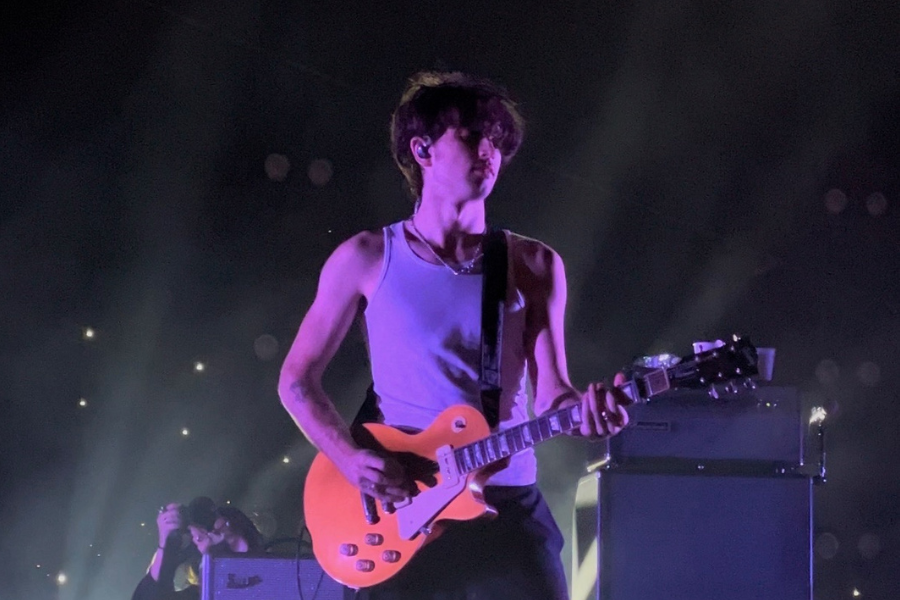

Elena Ferrante is a pseudonymous novelist best known for her Neapolitan Novels series. (Staff Illustration by Susan Behrends Valenzuela)

April 18, 2022

As soon as any writer has made it in the literary scene, it seems that they immediately come out with a book about writing. From Stephen King to Ursula K. Le Guin, these works share authorial techniques with the public and help burgeoning artists understand that every writing process looks different. In this context, one may find it odd that the famously pseudonymous Italian writer Elena Ferrante has decided to author a craft-based book of her own.

Released in English on March 15, “In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing” is Ferrante’s contribution to the instructional genre, containing a series of transcribed lectures. The Italian author has penned a series of standalone novels as well as the Neapolitan quartet, a collection of four novels that tell a singular story. She has risen to prominence in the U.S. following the translation of these works and has a similar audience to writers like Ottessa Moshfegh due to her ironic and intense portrayal of abandoned women. The fact that no one knows Ferrante’s true identity has also increased her popularity and appeal.

“In the Margins” is a strong collection and differs from the regular topics in Ferrante’s fictional works. Still, the author writes succinctly with her signature dry but creatively constructed style. In this book, Ferrante highlights how the writer should always ask themselves if their stories contain enough syntactical strength to function without utilizing their personal background as a crutch. The author sees this as a contemporary trend that every non-pseudonymous writer in the public eye falls into. Ferrante uses “In The Margins” to outline the alternative techniques that make up her own writing process. In addition, she also outlines the development of a more diverse literary canon.

Much of her style, Ferrante says, emerges from her study of classical writers like Dante, Dostoevsky and Keats — quintessential members of the predominantly male literary canon. Yet, in contemporary times, she urges women to create a literary style of their own that challenges this traditional masculine one.

The differentiation between the predominantly male traditional literary canon and a new inclusive form of writing in this formulation isn’t stereotypical. One wouldn’t be able to group all works in the traditional literary canon within a set of gendered characteristics or calling cards. For Ferrante, masculine writing is any writing by male author that has historically maintained a monopoly on the literary articulation of human experience. Ferrante’s conception of inclusive writing is a literature on the margins with untapped potential. It doesn’t have definitive rules and is still being formed by female authors and writers of other underrepresented demographics. “In The Margins” emphasizes that it is essential to build these literary movements so they can become classic like romanticism, realism and modernism.

Throughout the text, Ferrante celebrates a few female writers who prove that there are other ways of writing. This is most prominently displayed in her section on Virginia Woolf’s theory of storytelling, which outlines a kind of intentional ghostwriting that allows a story to speak through the writer, not vice versa. The writer, in this case, is not pushing their own agenda, and only serves as an intermediary between the created story and the tangible page. In re-examining Woolf’s approach, Ferrante looks to the existing alternative literary canon for literature’s path forward.

Ferrante agrees with Woolf and rewrites her theory to be less metaphorical. Ferrante instead argues that in the actual text of a novel, the writer doesn’t mean anything. What really matters about a work is the effectiveness of the story. Romanticizing the identity of the writer can cause a reader to find quality in a work that, technique-wise, is actually quite mediocre. Ferrante argues that a writer should be anonymous in their writing process and shouldn’t count on their biography to make their text stronger.

Of course, Ferrante’s literal anonymity makes this collection stand out against other writing how-to books. It feels as though a true master is relaying her wisdom to the reader — the writing speaks for itself.

For musings on writing, Elena Ferrante really is the contemporary author of choice. Her theories make her audience question their preconceived ideas about the craft. Her gaze is incisive, and her accusations recognize the vanity, guilt and noble purpose of the writer from inside the profession.

“In The Margins” makes one thing clear: Literature is not about the writer, even if it emerges from their mind. Once the writer has done the work of putting their story to paper, their responsibility for it is done. The author gives it away to the public in an effort to create a new canon. While writing, the author must do all they can to maintain control of their writing so that once released into the world, it can stand and thrive on its own.

“In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing,” translated into English and published with Europa Editions, can be purchased wherever books are sold.

Contact Lillian Lippold at [email protected].