Exhibit proves shocking, thrilling

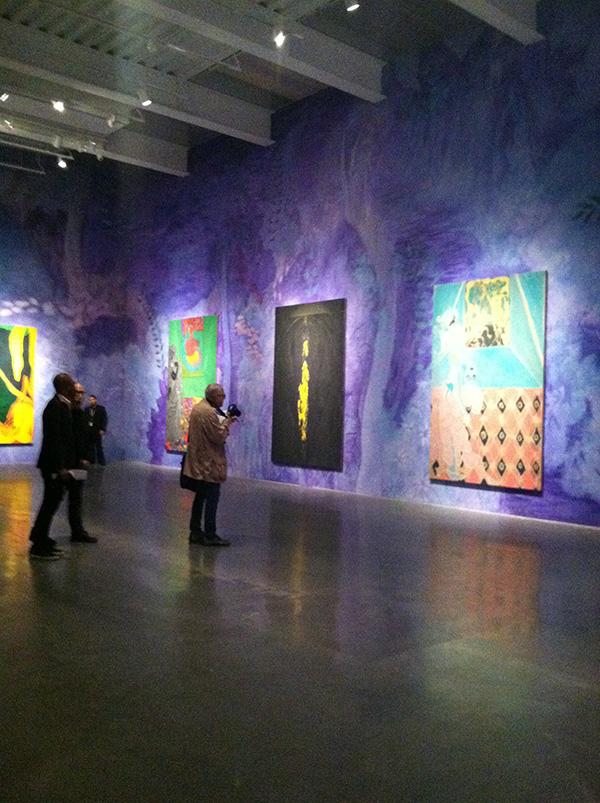

Chris Ofili’s new show, “Night and Day,” featuring colorful and jarring paintings, can be found in the New Museum.

“Chris Ofili: Night and Day,” the New Museum’s retrospective of the controversial British artist, opens with a shock to the system, the kind that makes it easy to forget that the rest of the exhibition even exists. Ofili’s work should not be surprising anymore — the almost two-decade-old, acrylic-on-linen paintings strewn with map pins, glitter and resin featuring blaxploitation-like heroes are known for their shock value.

In a classic moment in New York art history, former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani temporarily pulled city funding from the Brooklyn Museum after it showed Ofili’s “The Holy Virgin Mary” (1996) in its 1999 show “Sensation.” The work of art, like any of the paintings in this gallery, is still sensational today. It depicts a familiar personage — the blue-robed Virgin Mary, shown with her left breast exposed, depicted just as any Renaissance painter might have done it. It is not outlandish, however, to say no Renaissance artist would have painted the Virgin Mary as a black mother figure.

Few other painters in the history of art would have been so daring as to underline Mary’s sexuality by juxtaposing her with collaged porn images of black women exposing themselves. Fingers are ready for insertion while a religious figure sits ready for her portrait. This is not your grandma’s religious art.

Then there is the elephant dung, which at this exhibit replaces Mary’s breast and is thankfully scentless. The painting is propped against the wall instead of hung and, like all others in the gallery, it sits on two big balls of dung. Dung is a running motif in Ofili’s work, and it is used to defile his black subjects, who engage in all sorts of unspeakable activities. Though these works use it for shock value, his later red, black and green paintings, produced for the Great Britain pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, use it as a more poetic means by incorporating dung into the garish, colorful compositions.

Ofili’s influences are sometimes put front and center. In one particularly memorable painting, he reimagines Rodin’s “Thinker” as something like a black stripper, making it more Gauguin than Rodin and critiquing the ways artists commonly depict black subjects. Unfortunately, Ofili’s inspirations become more obvious and his work becomes less risqué as the exhibition progresses.

The beautiful 64-part “Afromuses” installation aside, “Night and Day” becomes less involved with ideas of racism, black images and ideology as the show continues. It also becomes less interesting. Though Ofili’s “Blue Rider” paintings depict that time of night when things are just barely visible, they lack any interesting subtext. They may recall the Rothko Chapel in their bluish darkness and installation style and they may be well-crafted, but they are plain. Only one painting, “Iscariot Blues,” in which a banjo player fails to notice a hanged man swinging among the leaves near his porch, has any lasting effect.

“Night and Day” climaxes with Ofili’s newest work, which is not memorable either. These thinly painted works about Trinidadian nightlife — Ofili has lived in Trinidad since 2005 — have little substance to their decidedly Cubist style. Still, they feel fresh, which is more than could be said for most artists’ work.

The New Museum’s exciting show is proof that Ofili cannot be pigeonholed into being a black artist who makes art about race. It may be less interesting when he leaves the topic he is known for, but “Night and Day” is nothing less than thrilling.

A version of this article appeared in the Wednesday, Oct. 29 print edition. Email Alex Greenberger at [email protected].

Alex Greenberger is an Editor-at-Large who has been at WSN since the first weekend of freshman year, bringing him to his sixth semester at the newspaper....