The splashes of paint sprawled across walls found in the Lower East Side take me back to the hues of New Delhi’s Lodhi Art District, snapping pictures of graffiti on expired film cameras. The cobblestone pavements of Washington Mews remind me of the stone pathways of Delhi’s Khan Market, where I spend my Sunday afternoons window shopping with my grandmother. And sometimes, when I’m lucky enough to get a peek of the Empire State Building between tall skyscrapers, I’m reminded of chasing views of Delhi’s Qutub Minar in my childhood best friend’s Volkswagen Polo.

These connections become ingrained in me as I encounter the commonalities between New Delhi and New York City.

In all of their elements — the nooks and crannies of bustling streets, the whiffs of fleeting yet evocative aromas, and the exchanged endearments among friends new and old — I find that I am deepening my understanding of home.

I am trying to find a feeling of home within a foreign place.

This surreptitious wall built into the corner of the ground floor boasts a mural of chaos and vulnerability. Different from a bookstore or a library bookshelf where art and books are perfectly arranged, the mural portrays a series of haphazard bookshelves, spilling inks, disheveled papers, scribbled Post-its and a blinking computer. Here, images of humanity and vulnerability portray the processes necessary for creative masterpieces.

Whenever I was caught in a labyrinth of thoughts that wouldn’t properly translate to paper, my father would take me to my childhood bookstore, the Full Circle Bookstore. Between the array of books and redolent selection of Agarbatti Incense Sticks, I’m allowed to be uninspired and inspired as I search for a hint of creativity. My father is sipping tea in a paper cup near the magazine section, flipping through a Vogue magazine. He doesn’t linger though, rather giving me space as I wrestle with writer’s block until a brilliant idea emerges.

In this space, I am allowed to be chaotic — my father ensures it. Both the mural and the bookstore hold comfort, prompting me to embrace creative blocks.

I miss Diwali and the familial mayhem this festival of love and light always brings.

Each year, my family and I argue about the daintiness of warm yellow lighting versus the eloquence of classic white. Discourse then ensues over what kind of Rangoli we’ll design — Will we use dyed rice granules to draw a peacock, or will we use rose and lotus petals to illustrate flowers? Following our petty quarrels, we put our pride aside and settle for a simple design: an Om, a symbol of oneness and truth in Indian philosophy, crafted from a deep red powdered quartz. We celebrate Diwali by praying to the god Ganesh and goddess Lakshmi for our family’s protection and eating fried and syrup-infused desserts until we pass out.

We do agree on one critical decorative component: the necessity to adorn each surface of furniture with orange marigold flowers.

Half-delirious from my 8 a.m. class and walking past the U ONE MARKET — a quaint little deli tucked under a maroon awning — I am drawn to this nostalgic smell trapped within a foliage of orange. For a fleeting moment, I am home with my family; I am intricately placing a string of marigold flowers onto the hem of my parents’ mahogany door. It’s soothing to carry a piece of home with me in the form of a bouquet.

When a friend of mine was visiting New York City, she made a list of 10 reasons why she doesn’t connect with the city. “The buildings make it congested [and] I can’t see as far as my eyes want to,” she wrote. To her point, most groggy mornings I can’t see past the fleet of black and yellow cars — even at 8 a.m.

Most mornings I’ve also been awoken by the grinding and drilling of machinery — and I’m usually a heavy sleeper. I suppose Delhi, too, is full of construction. Furnished buildings stand tall, piles of bricks lie everywhere at construction sites. Houses line up next to one another, and neighborhoods are separated by mere gates. Sometimes, this lack of space is frustrating.

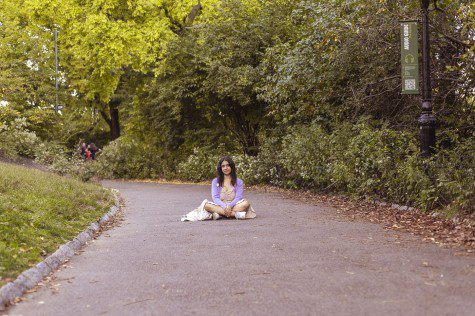

The trick to living in these cities is trying to unearth your own safe space — a haven of sorts. Liminal space is considered the time between what was and what is to come — a physical threshold between two time periods. A narrow, shrouded pathway close to The Lake in Central Park is my liminal space; it obstructs buildings and the concrete, rather presenting a view of flora. You know you can linger in this transitional, middle period comfortably.

New Delhi’s embassy and consulate area include massive houses for diplomats, but a few turns here and there expose you to empty roads with expansive greenery. A veil of Peepal trees conceal the houses, and you can’t hear a whisper from car engines. It’s bizarre to find a pocket of tranquility in a city so crowded.

There are days when I long to simply exist in this interstice. When I know I’m nearing burnout, I flee to parts of New York City and New Delhi that serve as the perfect respite — safe spaces that are mine to dwell in, away from the bustling world outside.

My father places an assortment of homegrown lilies tied together by a delicate thread on the desk in my childhood home. I adorn my new, blank dorm wall with green vines as homage to his fondness for gardening. I save a shared cigarette butt with my childhood best friend in a cellophane sheet on my pinboard back home, and I hang postcards from different countries gifted by new friends on my dorm wall. My mother’s annotated copy of “Little Women” sits on my bedside table. I secure the handwritten note my college best friend’s mum wrote for me on a container of homemade food.

I’ve come to think we’re all a collection of people we adore, places we live, things we cherish, scents we experience or tastes we relish. My dorm room wall is an attempt to encapsulate all of that. Each item hung or pasted is a tribute to beloved people, places and things.

It’s tough grappling with homesickness, especially when navigating a city so big and new. It’s natural to long for comfort and familiarity from the past, since that’s what we have known, but giving yourself the space to know this new environment is important. It’s only then that we can find new definitions of comfort, familiarity, family and home.