Play examines abilities of brain

Related stories

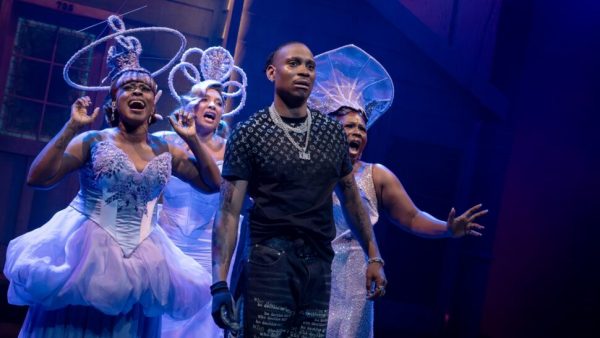

via facebook.com

For most of us, memory is supersensory. Recalling an event is more important than seeing it, smelling it or hearing it for the first time. But the sensation is fleeting, as actress Kathryn Hunter says at one point in “The Valley of Astonishment,” now playing at Polonsky Shakespeare Center.

“You can’t study a memory,” Hunter says. “It has no shape, no weight, no length.”

Yet for some people, experiences are multisensory even in the moment. Hearing a musical refrain may evoke splashes of color in the listener’s consciousness, or reading a word might bring to mind a certain shape or texture. This condition is called synesthesia, which essentially means “combination of senses.”

Written and directed by frequent collaborators Marie-Hélène Estienne and Peter Brook, “The Valley of Astonishment” presents several case studies of synesthetes, including Hunter’s character, Samy Costas.

Beginning the play working as a newspaper reporter, Samy is singled out for her unique abilities. She performs dazzling feats of memory, rattling off long lists of words or numbers as they had been read aloud to her moments earlier. Her editor sends her to visit a cognitive science lab, where she describes her mnemonic strategy of “encrusting,” which involves making an image for every word or phrase and then placing it within a mental map, so that eventually the streets and avenues in her mind become cluttered with the debris of past conversations.

“In order to understand the meaning of a word, I have to be able to see it,” Samy says.

The world of these phenomenal individuals is more colorful and musical than that of the audience, and it seems quite romantic. One young man, played by Jared McNeill, talks about what it was like to fall in love with music and to translate jazz into painting.

Yet, the synesthetes’ stories prove that the condition can be terribly overwhelming. At one point, Samy explains how the avenues and boulevards in her head have become too crowded to navigate, causing her to feel trapped in her own impressive memory. McNeill’s artist character tells one of the scientists that he has never been able to discuss his synesthesia before, always worrying that friends would call him insane. These characters think at extraordinary levels, but perhaps this only confines them to their own brains.

“The Valley of Astonishment” is extremely interesting without being cryptic or elitist. It may be a play about people who think outside the box, a subject that might normally lend itself to excess, but the production itself is spare. The set is simple, but not aggressively so, and while the few cast members do play several characters each, none of the actors make huge changes in their performance styles. There is not much dramatic action, but the nuanced subject of synesthesia is engrossing enough to excuse the flaws.

Brook and Estienne have chosen a topic that is very real while still bordering on the fantastical because synesthesia may be a legitimate phenomenon, but, for the average theatergoer, it seems far-fetched. Traveling with Samy through the “Valley of Astonishment,” audiences are forced to marvel at — and forced to fear — the capabilities of the human brain.

“The Valley of Astonishment” runs through Oct. 5 at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center, 262 Ashland Place in Brooklyn.

A version of this article appeared in the Wednesday, Sept. 25 print edition. Email Clio McConnell at [email protected].

Clio McConnell is a senior in the College of Arts and Science, studying Dramatic Literature and Classics. When she's not reading plays or casually translating...