New York Bail Policies Stifle Justice

April 25, 2016

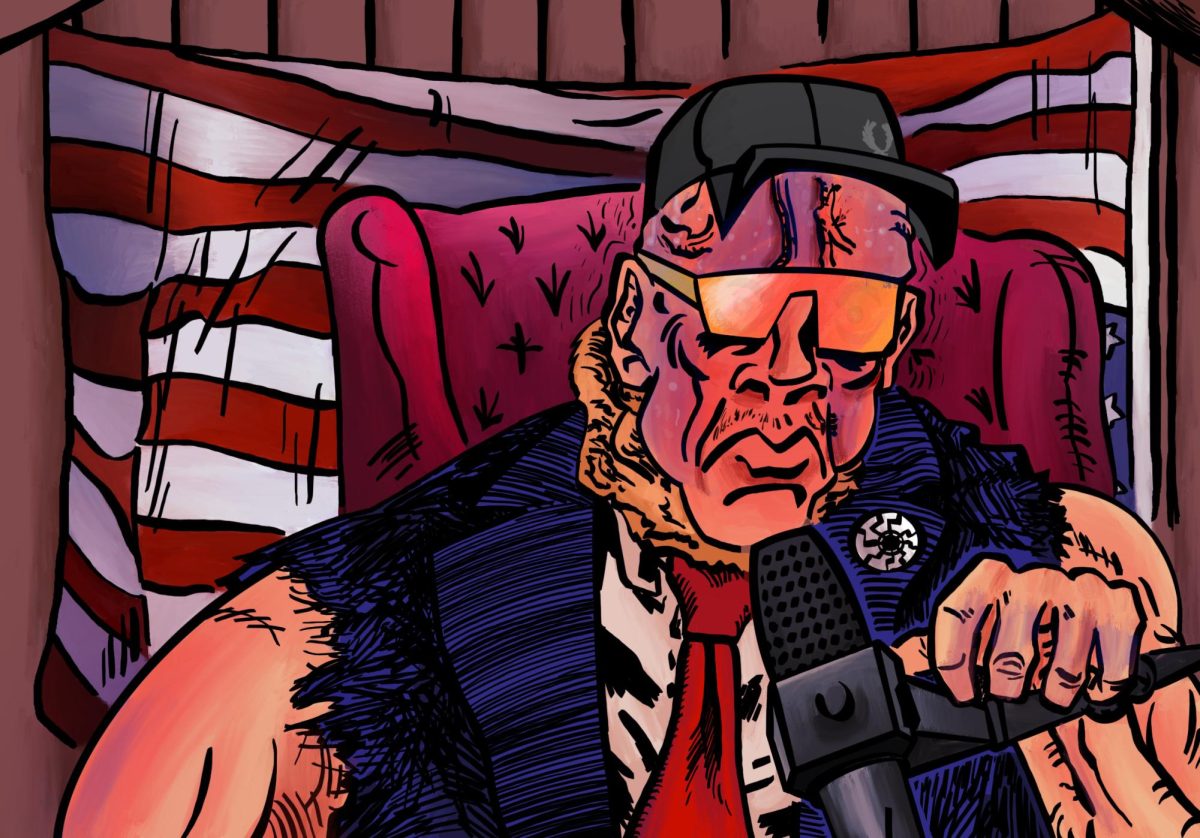

For poor black residents of New York, the defining trait of the criminal justice system is not justice — it’s punishment. From arrest to sentencing, racial biases pockmark the administration of due process and yield excessively unjust outcomes. However, there is one process housed in the criminal justice system which quietly delivers especially egregious and far-reaching decisions: the bail system.

In New York City, defendants often must post cash bail to stay out of jail in the interim period before their trial commences. Show up to your trial, and your bail money is returned to you. But if you can’t afford to post bail, you are faced with two options. You can continue to fight the charge and stay in jail until your trial concludes, which might get you fired from your job and kicked out of your housing. Or you can plead guilty, and go through life bearing an indelible mark of criminality. Thus, the cash bail system forces poor defendants to choose between the lesser of two unjust evils. Overwhelmingly, defendants in this situation plead guilty — 94 percent of state convictions are the result of guilty pleas.

Even more troubling, the sums of money which coerce defendants into accepting a plea bargain are astonishingly low. Bail set as low as $500 can prove unaffordable for many defendants. At Riker’s Island, 10,000 people a year spend their time pre-trial behind bars because they can’t afford a bail of $2,000 or less. For most NYU students, $500 might be an annoyance. But for a critical mass of people entrapped by the criminal punishment system, it is a heavy enough burden to permanently alter the trajectory of their lives. And the impact of bail isn’t limited to potential pretrial detainment — it also significantly affects the outcome of the case. For defendants who are detained for the duration of their trial, the conviction rate is around 92 percent. But for defendants who are able to post bail, return home and fight the charge without fear of losing employment or housing, the conviction rate is only around 50 percent. Cash bail incentivizes poor defendants to plead guilty in exchange for time served and needlessly inflates the number of citizens who bear the mark of a criminal record.

What are the alternatives? New York City has seen the implementation of a few useful stopgap measures, such as the creation of nonprofit bail funds in Brooklyn and the Bronx. These organizations post bail for defendants when bail is set at $2,000 or below, which gives the defendants a proper chance to affirm their innocence in a court of law. Of the Bronx Freedom Fund’s clients, not a single one went to jail for their charges.

Looking further into the future, however, the possibilities for reform are murky. Supervised release programs unnecessarily restrict a defendant’s freedom of movement, and allowing digital payment of bail wouldn’t eliminate the issue of unaffordability. This much, at least, is clear: the current system is profoundly broken and prevents the justice system from actually carrying out justice.

Opinions expressed on the editorial pages are not necessarily those of WSN, and our publication of opinions is not an endorsement of them.

A version of this article appeared in the Monday, April 25 print edition. Email Matthew Perry at [email protected].