Restyling Glossy Print for the Ballroom Floor

By Anna de la Rosa, Deputy Culture Editor

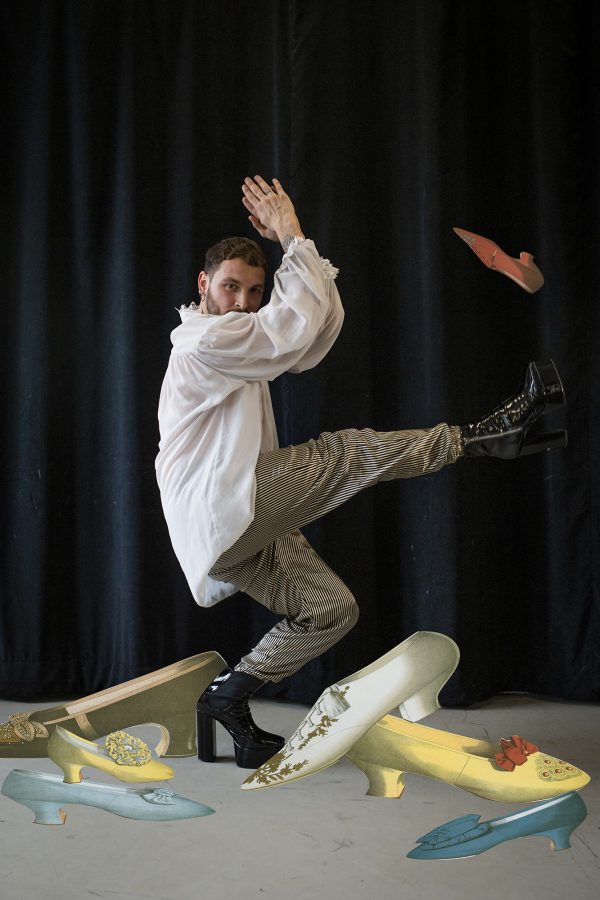

![]() trike a pose.”

trike a pose.”

For many, the word “Vogue” brings to mind Madonna’s iconic 1990 black-and-white music video. In a sleek black pantsuit with her hair coiffed in a ’20s-reminiscent bob, the renowned singer hits and “clicks” her arms in sharp movements to frame her long lashes and sultry pout. Her movements, however, remain fluid rather than defaulting to a staccato.

People may assume Madonna’s model-like poses were inspired by the glossy pages of the acclaimed magazine of the same name, but this isn’t the full story. The pop queen’s video actually references dance moves — inspired by the fierce positions of the models in Vogue magazine — she saw at Manhattan’s Sound Factory Bar in 1989.

While voguers manage to look as if they were born naturally dripping in finesse, this physical prowess is only cultivated through hard effort and dedication from those seeking to achieve the rank of an icon. The angularity and rigidity of these precise arm and leg motions are softened by feats of flexibility. When performed correctly, the symmetrical movements appear effortless.

In the 1970s and ’80s, the underground drag ballroom scene brought voguing to center stage. The balls were competitions that consisted of individuals, usually drag queens, who would perform in different genres and categories. During the ’20s, ball culture emerged in New York City as an exclusive phenomenon, which led black and LGBTQ communities in Harlem to establish their own in the 1960s — with a twist.

Queer individuals, particularly those of color, competed in various categories such as Butch Queen (cisgender gay men), Sex Siren (oozing sex appeal) and Face (emphasis on facial features). While balls and competitions were taken seriously, they primarily offered a space for those not accepted by society to be who they wanted to be in a nonviolent and liberating way.

The epitome of acceptance and foundation for the communities within ball culture were the Houses. The Houses would compete against each other, and each typically had a defining feature that the members identified with — for example, the House of Xtravaganza was known for having the prettiest faces.

One House transformed the underground ballroom into a stage for dance. Willi Ninja, the founder of the House of Ninja, is recognized as the “Grandfather of Vogue.” He began dancing at seven and his self-taught talent led him to Greenwich Village in the late 1970s. While Ninja did not invent voguing, his stylized movements redefined and legitimized the dance form, making it something that could be taught to the Virgin Vogue, or the newcomers to the ball scene.

A living legend and the first Father of the House of Ninja, Archie Burnett saw Ninja as a brother. Burnett started voguing as the accidental product of being exposed to parties and clubs, such as Tracks Cafe, where voguing was taking off. He remembers the day when Ninja came bursting into rehearsal stating he was going to create a House.

“[Willie] lived in Flushing, Queens, which was a very Asian-populated neighborhood, and [he] was very interested in the martial arts,” Burnett wrote in an email to WSN. “He was an enthusiastic martial arts movie aficionado!”

Captivating every person’s attention at the ball, Ninja duck-walked while clicking his arms, moving seamlessly into a dip. He threw his legs over his shoulders while twisting his back and bending his fingers, leaving no body part stagnant as he performed. Burnett explained how voguing music — which evolved from disco and Philly soul to “pounding house beats” — was crucial to informing these sharp and agile movements.

“You are creating pictures and poses that move within [the] time aspect of music, and the goal is to make a perfect picture with each click or beat that the music provides,” Burnett said. “You challenge yourself to create patterns and musicality within the framework of how a two-dimensional source as a picture will be translated with a three-dimensional body on beat.”

Complete with pops and spins, voguing movements were used to throw shade, or subtly insult toward one’s opponents. While these motions made to kill the competition were jerky and contorted, Ninja was graceful, living up to his namesake.

Some balls were held to practice realness, or the ability for queer participants to pass as straight. Dancers dressed up as realities that they couldn’t take on, whether it was as a corporate executive or a supermodel. While some may argue that these behaviors qualify as glorification or stylization, they were merely means of survival — practicing putting on a convincing front to be able to survive the real world and its harsh view of queer and marginalized individuals at the time.

While the drag ball scene and voguing were products of the LGBTQ culture in New York City, they also served as gender fluid displays that both gave a home to and reflected the many nonconforming voices in society.

Ninja was one of the stars of Jennie Livingston’s award-winning 1990 documentary, “Paris Is Burning.” Livingston, who was first exposed to voguing in Washington Square Park while she was taking a summer class at NYU, highlighted the lives of the people in the Harlem drag scene during the late 1980s. Madonna released the music video for “Vogue” in the same year as the film’s release, thrusting voguing into the spotlight and pushing the drag ball scene from the hidden edges to a commercialized space.

Even as a current icon who lived during the birth of voguing and played a major role during its evolution, Burnett himself struggled with his identity within the voguing culture.

“Not being gay presents its own challenge in a culture that is identified as such,” Burnett said. “I have a saying — ‘you can be in the scene, but you don’t have to be of the scene.’”

Voguing has since grown to transform and inform other dance styles. A former Martha Graham Dance Company principal-dancer-turned-freelancer, Abdiel Jacobsen combines voguing with the hustle, a social partner dance performed in ballrooms and nightclubs to disco music.

“I work with Archie [Burnett] and take a lot of of the vogue elements of dancing and presence and integrate it into the hustle,” Jacobsen said. “That’s the way [I] can be more creative.”

Voguing has essentially become an accredited dance form that continues to be celebrated in pop culture, music and fashion. It is reaching new levels of folklore, and queer and transgender individuals have seen increased visibility as models, artists and musicians — all opportunities once seen as impossible by Ninja’s generation. The 2018 FX series “Pose” created by Ryan Murphy, for example, offers an uncensored look into voguing culture and has been lauded by critics and viewers across the U.S.

However, while transgender models like Leiomy Maldonado star in Nike advertisements and voguing dancers like Dashaun Wesley are being sent to dance schools in St. Petersburg to teach the dip, many transgender and queer people remain vulnerable. This cultural paradox remains a struggle for many marginalized members of the community who are trying to achieve their dreams in a world where the American Dream seems unattainable.

Despite the disparity, voguing represents resilience in a time when the future can appear bleak. The ability to form a new community in the midst of social persecution and create something beautiful and liberating speaks more to American grit than anything else.

“This is an urban art form that was born out of a certain type of struggle that speaks to a larger demographic — more than the one that it was intended for,” Burnett said.

Email Anna De La Rosa [email protected]. A version of this article appears in the Thursday, April 4, 2019, print edition on Page 5. Read more from Washington Square News’ “Arts Issue Spring 2019.”